ATTRA Identification Sheet: Apple Diseases

By Tammy Howard and Guy K. Ames, NCAT Agriculture Specialists

There are several key diseases that affect apple production. Use this handy guide to help identify some diseases and to learn more about causes and solutions. For more specific information about these diseases, or to learn about apple diseases not addressed here, see ATTRA’s publication Apples: Organic Production Guide.

Symptoms

Photo: NCAT

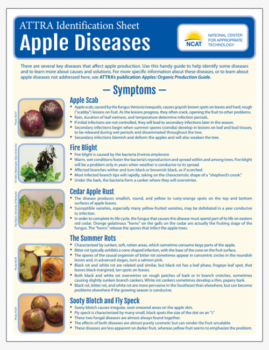

Apple Scab

Apple scab, caused by the fungus Venturia inaequalis, causes grayish-brown spots on leaves and hard, rough (“scabby”) lesions on fruit. As the lesions progress, they often crack, opening the fruit to other problems.

Rain, duration of leaf wetness, and temperature determine infection periods.

If initial infections are not controlled, they will lead to secondary infections later in the season.

Secondary infections begin when summer spores (conidia) develop in lesions on leaf and bud tissues, to be released during wet periods and disseminated throughout the tree.

Secondary infections blemish and deform the apples and will also weaken the tree.

Photo: TJ Smith, Washington State University

Fire Blight

Fire blight is caused by the bacteria Erwinia amylovora.

Warm, wet conditions foster the bacteria’s reproduction and spread within and among trees. Fire blight will be a problem only in years when weather is conducive to its spread.

Affected branches wither and turn black or brownish black, as if scorched.

Most infected branch tips wilt rapidly, taking on the characteristic shape of a shepherd’s crook.

Under the bark, the bacteria form a canker where they will overwinter.

Photo: NCAT

Cedar Apple Rust

The disease produces smallish, round, and yellow to rusty-orange spots on the top and bottom surfaces of apple leaves.

Susceptible varieties, especially many yellow-fruited varieties, may be defoliated in a year conducive to infection.

In order to complete its life cycle, the fungus that causes this disease must spend part of its life on eastern red cedar. Orange gelatinous “horns” on the galls on the cedar are actually the fruiting stage of the fungus. The “horns” release the spores that infect the apple trees.

Photo: NCAT

The Summer Rots

Characterized by sunken, soft, rotten areas, which sometime consume large parts of the apple.

Bitter rot typically exhibits a cone-shaped infection, with the base of the cone on the fruit surface.

The spores of the causal organism of bitter rot sometimes appear in concentric circles in the roundish lesion and, in advanced stages, turn a salmon pink.

Black rot and white rot are related and similar, but black rot has a leaf phase, frogeye leaf spot, that leaves black-margined, tan spots on leaves.

Both black and white rot overwinter on rough patches of bark or in branch crotches, sometimes causing slightly sunken branch cankers. White rot cankers sometimes develop a thin, papery bark.

Black rot, bitter rot, and white rot are more pervasive in the Southeast than elsewhere, but can become problems elsewhere if the growing season is conducive.

Photo: NCAT

Sooty Blotch and Fly Speck

Sooty blotch causes irregular, soot-smeared areas on the apple skin.

Fly speck is characterized by many small black spots the size of the dot on an “i.”

These two fungal diseases are almost always found together.

The effects of both diseases are almost purely cosmetic but can render the fruit unsalable

These diseases are less apparent on darker fruit, whereas yellow fruit seems to emphasize the problem.

Key Low-Spray and Organic Solutions

Apple Scab

The use of scab-resistant varieties is the best long-term strategy for organic growers. The number of primary and secondary infections in a year depends on the amount of rain. The warmer the weather, the more quickly conidia development follows primary infection. If the grower is relying on protective-type fungicides, including all organically acceptable fungicides, trees should be treated whenever there is a chance of primary infection. Apple scab can be controlled on susceptible varieties by timely sprays with fungicides. For the organic apple grower, there are three commonly used materials: sulfur, lime-sulfur, and Bordeaux mixture. Potassium bicarbonate (the trade name is Armicarb) and potassium phosphonate (Resistim), in combination with sulphur, were very effective at controlling the fungus. Trees must be sprayed or dusted diligently before, during, or immediately after a rain, from the time of bud break until all the spores are discharged. Because the scab fungus overwinters on fallen apple leaves, growers can largely eliminate the primary scab inoculum and control the disease by raking and destroying the fallen leaves. Neem has also demonstrated some efficacy in managing scab.

Fire Blight

Where fire blight is a problem, cultural practices that favor moderate growth, such as low fertilization and limited pruning, are recommended. Once infection has occurred, there is no spray or other treatment—beyond quickly cutting out infected limbs—that will minimize damage. Proper sanitation is the most important measure for controlling fire blight once it has infected a tree. Bordeaux mix and other copper formulations sprayed at green-tip stage are organic options that provide some protection from infection. The antagonistic bacteria Pseudomonas fluorescens (Blight Ban A506) is commercially available to prevent colonization of the blossoms by Erwinia amylovora during bloom. BlightBan cannot be used in combination with copper sprays.

Cedar Apple Rust

Removal of eastern red cedar around the immediate orchard vicinity can reduce the inoculum reaching the apple foliage. In addition, there are many rust-resistant apple varieties. Many fungicides are effective against rust, including the sulfur-and-copper compounds, which are approved for organic production as a last resort in an organic pest-management plan.

The Summer Rots

For control in organic orchards, growers should emphasize cultural techniques for suppressing the causal organisms of these rots. Such techniques include pruning out diseased wood, removing fruit mummies, pruning for light penetration and air circulation, and avoiding poor sites. Piles of prunings can be a source of infection, so remove prunings from the orchard or burn. There are several apple varieties that demonstrate some resistance. A number of biological controls have demonstrated effectiveness against post-harvest rot organisms and are labeled for fruit-rot organisms in general. For post-harvest fruit rots, cultural controls are best combined with a biological antagonist such as Bacillus subtilis or Trichoderma viridi. Harvesting and storage sanitation practices will help prevent these rots.

Sooty Blotch and Fly Speck

Planting early-maturing, dark-red apple cultivars can reduce the damage caused by sooty blotch and flyspeck. For the organic orchardist, pruning to maintain adequate air flow through the canopy is very important. Potassium bicarbonate (KHCO3) is a new, moderately effective fungicide for control of sooty blotch and fly speck. An amino acid combination of dl-methionine and riboflavin, freshly mixed and supplemented with sodium dodecyl sulfate and a trace amount of copper sulfate, controlled the complex as well or better than the standard sulfur spray. A post-harvest soak for five minutes in a 5 to 10% bleach solution in water has shown effectiveness for sooty blotch control.

ATTRA Identification Sheet: Apple Diseases

By Tammy Hinman and Guy K. Ames, NCAT Agriculture Specialists

Published November 2014

©NCAT

IP484, slot 496

This publication is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. ATTRA.NCAT.ORG.