Community Supported Agriculture

By Daniel Prial, NCAT Agriculture Specialist

Since its introduction to the United States, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) has been a model for connecting people with where their food comes from. By encouraging customers to become shareholders in the farm business, CSA gives farmers a chance to spread both the risks and the rewards of farming across a larger community. This publication provides a foundation and tools for farmers looking to begin a CSA operation. It also explores many variations to the traditional model that have developed over the last generation and looks into what the future might hold for CSA.

Why CSA?

For many farmers, their products are about more than just selling a commodity. They grow food to share with their families, to feed their towns, and to help the people around them. And, they strive to do this while running a profitable farm business. This publication presents Community Supported Agriculture (CSA): a farm business model that seeks to help farmers feed their communities while remaining in the black. This publication explores the origin of the CSA idea and explains how to start a CSA operation, reviews different structures and marketing needs, presents variations to the traditional CSA model, and discusses the future of CSA in the United States.

CSA is, at its core, a system for building a network of support around a farm business. Generally, before the growing season, customers buy a membership or share in a farm operation by sponsoring the farm costs that year. As a return for their money, they then receive products regularly during the growing season: traditionally, a box full of vegetables each week. If the farm, for any reason, should face a bad year and production drops, the members share in that risk. The CSA model, put simply, is a community supporting its local farm operation and sharing in both the risks and the rewards.

Two Definitions of CSA

“In basic terms, CSA consists of a community of individuals who pledge support to a farm operation so that the farmland becomes, either legally or spiritually, the community’s farm, with the growers and consumers providing mutual support and sharing the risks and benefits of food production. Members or shareholders of the farm or garden pledge in advance to cover the anticipated costs of the farm operation and farmer’s salary. In return, they receive shares in the farm’s bounty throughout the growing season, as well as satisfaction gained from reconnecting to the land. Members also share in risks, including poor harvest due to unfavorable weather or pests.”

—Suzanne DeMuth, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA): An Annotated Bibliography and Resource Guide (1993)

“Community Supported Agriculture is a connection between a nearby farmer and the people who eat the food that the farmer produces. Robyn Van En summed it up as ‘food producers + food consumers + annual commitment to one another = CSA and untold possibilities.'”

—Elizabeth Henderson with Robyn Van En, Sharing the Harvest (1999)

For farmers, this means a distribution of potential risk. If a major drought should hit the area, all the members of the CSA share in the impact of a reduced harvest. It also provides the farmer a more guaranteed income, which can come before the growing season. This helps reduce a farmer’s need to take on debt. Farmers running a CSA still need to spend time marketing their CSA, plus recruiting and maintaining their member lists. Although it can be an attractive idea, running a CSA operation can be extremely difficult for beginning farmers who need to balance production of a large variety of crops with the management of a customer base.

For customers, CSA provides a direct connection to their food system. They are in regular communication with their farmer. They can eat with the change of seasons. Often, CSAs are cost-effective for a customer, especially for high-end, organic produce. Additionally, many studies suggest being a CSA member/shareholder improves health through increased vegetable consumption (Hanson et al., 2017).

A properly run CSA supports small-farm sustainability. As a sustainable operation, a CSA provides benefits in three categories: economic, social, and environmental. Economically, CSAs balance out the farmers’ fiscal year, making more capital available at the beginning of the growing season, when it is most necessary. Socially, CSAs build connections between farms and their communities, thus ensuring that more people have stake in the farm’s success. Environmentally, the economic support allows the farmer to plan better and therefore gives the flexibility to manage the soil better. The CSA market model also pushes farmers to focus on crop diversification, which reduces the impact from pests and diseases.

Understanding the Terms

The language around CSAs has gotten a little muddled over the years. Technically, the letters C, S, and A stand for Community Supported Agriculture, referring to the theory of farmers and their communities working together. However, over time, the letters have also come to mean the CSA operation itself. For example, a farmer might say: “I’ve added a CSA to my farm business this year.” Because of this, it is common to see the plural term “CSAs.” For example: “Many farmers are bringing their CSAs to New York City.”

Most sources say that CSAs in the United States began in 1986 when two farms in New England offered shares in their season’s harvest: Indian Line Farm in Massachusetts and Temple Wilton Community Farm in New Hampshire. The idea was not new. Farmers in Europe and Japan had been operating CSAs for at least two decades, and one of the founders of Temple Wilton Community Farm had been part of a CSA operation himself in Germany (Josephine Porter Institute, 2016). Before 1986, it is possible that many farmers had adopted the similar “Clientele Membership Club” model designed by Dr. Booker T. Whatley, a Tuskegee University professor and sustainable agriculture advocate. Whatley’s goal was to give black Americans on small farms a competitive edge over large, industrialized farms (Bowens, 2015; Mother Earth News editors, 1982). Asking for a membership fee and building a captive customer base (the principle behind CSA) does just that. It is difficult to find data, however, on how widespread the adoption of Clientele Membership Clubs was.

Common to all CSA models is a core philosophy: local farms need community support to thrive. This philosophy relies not only on community money, but also on community contact. The CSA model is a direct-to-consumer model. In most modern agriculture markets, the customer and the farmer are in opposition: the customer tries to get the lowest price and the farmer tries to get the highest. With the CSA model, the customer and the farmer work through cooperation and agree on the prices beforehand.

Many CSA farmers don’t see CSA as a philosophy as much as a sophisticated marketing model and cash-flow-control instrument. It’s a way to have a contract with a diversity of buyers, a way to get up-front cash, and a way to capture a client base.

Philosophy, marketing model, or both, CSAs are becoming more and more popular. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported that 12,617 farms sold product through a CSA in 2012 (USDA, 2016), a greater than twelve-fold increase since this publication was first published in 2006. At the time of this publishing, the 2017 Ag Census data had been released, but the USDA had not yet released data on the number of CSAs. It is likely that the number of CSAs in the country is currently even higher.

Before Starting a CSA

Traditionally, CSAs have been vegetable operations. Shareholders pay to become members, usually in the realm of a hundred dollars per month for the length of a season. Typically, once per week during the growing season, members come pick up their share on the farm or at a designated pick-up point. The growing season varies in length, based on location. A six-to-seven-month CSA in New England is able to run that long by using season-extension techniques. In California, a CSA can easily run year-round.

Before starting a CSA, farmers need to have an understanding of their farm’s business structure. ATTRA has many publications that can help with this, starting with Evaluating a Farming Enterprise. Also, Farm Commons, an online source for free legal advice for farmers, has resources for building a legally sound CSA. Its Legally Resilient Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) Program Guide is not a replacement for a good lawyer, but it does provide a helpful framework for a future conversation with one (Armstrong et al., 2016).

Farmers also need to understand their finances before beginning a CSA plan. One of the earliest CSA models in the United States, Temple Wilton Community Farm, asks the farm manager to make a presentation to all of the CSA members and to lay out the annual farm budget. Members are therefore able to see exactly what the farm manager expects in costs: materials, seeds, labor, etc. (Galt, 2013). Most CSAs are not this transparent, but farmers still need to be clear about costs for themselves before setting the annual price per share. ATTRA has many business planning resources.

After determining a budget, farmers need to decide how members will pick up their shares. If the pick-up site is on-farm, will there be enough parking for everyone? Is the farm safe enough or clean enough to have CSA members wandering around the gardens or fields? Does the farmer have enough liability insurance? Do zoning laws allow this activity? If the pick-up site is off-farm, the farmer will need to answer even more questions based on the location. For example, does the site have refrigeration to keep the boxes of product fresh? Is it in the shade? Alternatively, will the farmer circumvent pick-ups entirely and offer delivery of shares?

Packing the shares can be a multi-person, assembly-line operation. Full Belly CSA in California has its bulk crates brought straight to a rolling table and half-a-dozen people or more pack the boxes. Photo: Rex Dufour, NCAT

Packing the shares can be a multi-person, assembly-line operation. Full Belly CSA in California has its bulk crates brought straight to a rolling table and half-a-dozen people or more pack the boxes. Photo: Rex Dufour, NCAT

Postharvest Handling of Fruits and Vegetables

A large CSA operation can move enough food in a single afternoon to feed hundreds, if not thousands, of families. When that much produce is moving around, farmers must focus on food safety. As produce comes out of the fields, it needs cooling, washing, and storage to stay fresh for the pick-up day. Before starting a CSA, a farmer needs to ask if the farm operation can adequately handle the amount of product moving through while also keeping it safe for consumption.

CSA: Planning for Profit

Farming, including vegetable production (most CSA farms focus on vegetables), is a highly complex, financially risky career, demanding great creativity and professionalism. Starting a CSA is not the wisest choice for the beginning farmer. The operation, from the very start, will face the dual challenges of production and post-harvest techniques, while simultaneously managing the needs of the customer base.

Many farmers feel that one of the chief advantages of a CSA is a ready supply of up-front cash at the beginning of the season, but it is an advantage that only comes as a result of lots of hard work and planning.

To start a new CSA, a farmer needs to have a very clear idea of the costs of production on the farm. This means a full farm budget, including the obvious costs: seeds, materials, equipment, etc. It also includes the less-commonly-budgeted labor costs, depreciation costs, insurances, retirement costs, and health insurance costs. The farmer then works backward to figure out how many shares it will take—and at what price—to meet those costs.

Full shares from Fully Belly CSA, packed in waxed boxes and ready for distribution. Photo: Rex Dufour, NCAT

Full shares from Fully Belly CSA, packed in waxed boxes and ready for distribution. Photo: Rex Dufour, NCAT

In terms of the up-front capital that running a CSA provides, acquiring a Farm Service Agency or operating loan can also be a source of cash. Over the course of a season, the interest rates, and therefore the costs of that money, could potentially be quite low. If a farm already has a dedicated market (and that market has a low cost of entry), then such a loan could be much simpler for a farmer than producing crops, managing a CSA, and building a community.

Finally, there are no simple answers in creating a sustainable farm business. More and more, CSA operations make up just a part of a farm’s financial profile. A single farm might run a CSA, sell at a farmers market or two, and also sell to local restaurants and food hubs. For more information about successfully running a farm business, see the ATTRA publication Planning for Profit in Sustainable Farming.

Structuring the Share

Because CSA is inherently a connection between a farm and the community around that farm, every CSA operation structures itself differently. CSA farmers need to decide how long their growing seasons will be, what a share will look like throughout the year, and what flexibility members will have in a share.

Traditionally, CSAs offer summer and fall shares and provide members with boxes of vegetables harvested directly from the field on a weekly basis. But if a farm is looking to expand into more seasons, perhaps it should consider storing root vegetables and offering an extra winter share for its customers.

Farmers need to be clear about what comes in the share. If a share is a box of vegetables, how big is the box? What are the vegetables? How often will a share arrive? What will it cost? The answers to these questions depend on the farmer’s financial picture and on the crop plan for the season. They also can be influenced by what other local farmers are doing.

Traditionally, farmers choose what goes in the CSA share based on the harvest, but many CSAs now offer their members choice about the contents of their boxes each week. This freedom to choose can be restricted or open (see inset). When the farmer offers choice to CSA members, the CSA experience feels more like shopping, it is a little less foreign to new members, and it lets members only take the product they know they will eat. Many CSA-management software programs offer customers choices before they even get to the pick-up location. See the section on Software for Managing a CSA.

Choice in a CSA Share

Whether or not to offer members choice in their CSA shares can be a tricky question. On one hand, providing members the ability to choose what products they get in their box can help them feel fulfilled with their purchase—and thus be more likely to remain a member year after year. On the other hand, giving members choices could mean that no one chooses any of the tatsoi that the farmer experimented with this year.

Here are two examples of market-style CSA shares:

Picadilly Farm, New Hampshire

Picadilly Farm has a CSA “shop” on the farm, and local members can visit Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. The farmers stock the shop with fresh produce and the members choose eight or nine items from what is available. While on site, members can also visit a small Pick-Your-Own garden. Non-local members receive a traditional CSA bushel box.

Potomac Vegetable Farms, Virginia

The Newcomb family has been farming for more than 50 years and has run a CSA since 2000. In addition to pre-boxed shares, Potomac Vegetable Farms has a unique “market-style” pickup. Every shareholder comes in each week with a certain number of points based on their share size. Members spend these points on the produce options at the market. If Potomac Vegetable has a bumper crop of zucchini, for example, they can lower the point-per-unit cost to encourage the members to take some home. They essentially create their own currency.

Picadilly Farm, in Winchester, New Hampshire, sets out harvest crates and lets customers select products, within certain guidelines. Photo: Andy Pressman, NCAT Picadilly Farm, in Winchester, New Hampshire, sets out harvest crates and lets customers select products, within certain guidelines. Photo: Andy Pressman, NCAT |

Potomac Vegetable Farms, outside of Washington, DC, allows shareholders to “shop” for their produce. Photo: Hana Newcomb, Potomac Vegetable Farms Potomac Vegetable Farms, outside of Washington, DC, allows shareholders to “shop” for their produce. Photo: Hana Newcomb, Potomac Vegetable Farms |

Pricing the Share

For many potential CSA members, dropping hundreds of dollars at the beginning of the season may be too much of a commitment. As an option, many CSAs offer half-shares. For half the cost of a full share, either members get a smaller amount of product or they only pick up their product every other week. So, if a 20-week share costs $400 and provides a box of vegetables once per week, a half-share could be $200 (or more) for either half a box of vegetables every week or a full box every other week.

The half-cost share is just the tip of the share iceberg. Some farms offer micro-shares designed for a single person and others offer large family shares designed for five or more people. There are even workplace snack shares with only vegetables and fruits that do not need to be cooked.

Other CSAs offer a pay-as-you-go model to reduce the feeling of commitment. J&P Organics Farm in Salinas, California, offers a year-round pay-as-you-go CSA for about $25 per box. There is no membership and no commitment. Customers put in an order and receive a box of vegetables delivered to their doorstep once per week. A large enough pool of frequent subscribers (who place weekly orders) supplement the infrequent subscribers (who order less than one box per month) (Freedman and King, 2016).

Some CSAs ask for only half the money down before the season and the other half partway through. Others ask for monthly payments.

No matter how a farmer decides to charge the customer, the farmer needs to have an understanding beforehand of the entire season’s costs of production. That way, the farmer can spread those costs over the number of shareholders and months to figure the price per share accurately. Once that price is set, there is no raising it halfway through the season to try to raise a little more revenue.

Building Community through Pricing

Depending on your farm needs and your own personal farm goals, there are powerful methods to build community around your farm through the actual pricing of your shares.

For example, the Temple-Wilton Community Farm brings all shareholders into one room, shows the farm budget, and then asks for financial pledges. This model encourages shareholders to pay what they can. People with more means end up paying more for their share than people with less means, but everyone has the same access to farm product (Prial, 2018).

Elizabeth Henderson’s Peacework Farm (which evolved from Indian Line Farm) also shared the farm budget and set the actual value of the share: the full budget divided by the number of shares. The farm then offered a sliding scale of prices and set recommended share prices based on household income. This allowed lower-income members access to the same farm product. It was not prescriptive, however, and the CSA sign-up asked members to “contribute only what is realistic for your household, while truly considering the value the farm and its food bring to your home” (Henderson, 2019).

The key difference between the two models is the public vs. private contributions. Both of them, however, set up a system where some members support other members, so that all have access to fresh farm products.

Share Add-Ons

Offering add-ons is another common way to diversify the regular share that members receive. Because the members are already a captive audience, very little marketing is required for new products. For example, a vegetable CSA can add a dozen eggs per week for a few extra dollars. Flowers are also a common add-on to a share.

Other CSA Structures

Other broad ways to structure shares include:

- Pledge-based shares: At the beginning of the season, all members gather and pledge what they can toward the farm’s operating cost. If the full cost is not met, then the expectation on the farmer is reduced or more pledges are made.

- Sliding shares and subsidized shares: The cost per share varies based on member income. Wealthier members pay more per share, allowing lower-income members to still buy into the CSA. This also functions with external subsidies: for example, CSAs subsidized by health-conscious workplaces or CSAs subsidized by health-research non-profits.

- SNAP: CSAs can take payments from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) / Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT). SNAP, formerly known as food stamps, is a federal program that assists low-income individuals and families in buying food staples. Accepting SNAP benefits on-farm requires authorization by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service and getting a machine that can process EBT cards (USDA, 2015). EBT is the technology that processes SNAP benefits. In addition, many states now offer incentive programs in which vegetable purchases are matched 1-to-1, which can effectively lower the cost of a share for someone with SNAP benefits by 50%. The farmer receives the other 50% from subsidizing agencies or organizations. This is similar to “Cost Offset CSAs” discussed below.

For more information about how a CSA operation can accept SNAP benefits, see the ATTRA tipsheet Outreach Tips for Farmers that Accept SNAP for CSAs.

For more ideas on how to set up a CSA, refer to the section below on Variations to the Traditional CSA Model.

Marketing a CSA

Enjoy Interacting with Customers

A farmer interested in starting a CSA first needs to ask herself if she enjoys interacting directly with her customers. CSA members are often buying more than just a service. They’re buying a social connection to their farmer. Putting a premium on the one-on-one, person-to-person interaction is key to marketing a CSA.

The Story Farmers Tell

With all marketing, farmers first need to know their goals for having a farm and, as such, what story they tell with their marketing. For example, Foggy Hill Farm in Jaffrey, New Hampshire, has a goal of feeding its direct community. The farmers could perhaps make more money growing vegetables for contracts, but they choose to run a CSA because they value the community connection. They grow calorie-rich foods that tend to have a lower price value instead of high-value, boutique crops. As such, when they market their CSA, they market their farm’s focus on building and feeding its community.

Communicate the Benefits

Farmers need to communicate the benefits of joining a CSA to their prospective members. Generally, these benefits include the following:

- Obtaining high-quality, fresh food

- Supporting alternative or organic agriculture

- Improving health through increased vegetable consumption

- Making the environment healthier

- Having a relationship with local farmers and the food system

This list comes from a California-specific survey of why CSA members chose to join a CSA and is generally similar across the country (Christensen et al., 2015).

Farmers also need to be clear about their price points and what their members get for that price. For example, Hillside Springs Farm in Westmoreland, New Hampshire, prices its full share at $600 and says on the farm’s website that an equal amount of equal-quality produce from a local health food store would cost twice that: $1,200 (Hillside Springs Farm, 2018).

Know the Customer

According to regional and national studies, CSA members are generally young, educated, and at least middle-class. The vast majority are female—in some studies, the numbers are as high as 85%. The studies show that being a member of a CSA usually means that the person is also vegetarian and/or pro-environment. CSA members generally recycle and cook at home (Christensen et al., 2015; Vassalos et al., 2017).

Here are some questions to consider when trying to understand a client base:

- What do my stereotypical clients like? How old are they? Are they supporting a family?

- What do my clients do for work? Are they financially comfortable?

- What values do my clients hold? What do they believe in?

- What do my clients need? What keeps them awake at night?

- Where are my clients in their lives that they will see advertising from me? What newspapers do they read, shops do they visit, blogs do they browse?

- What will stop my clients from buying my share? How do I get in front of those issues?

The idea is to hyper-personalize the marketing process and not just be running numbers and spreadsheets. Marketing a CSA needs to be deeply personal—CSA’s greatest strength is the customer-farmer relationship—and answering these questions can help a farmer think about customers as individuals, even before there is a person-to-person relationship.

Learn from the Competition

Farmers have needed to market their CSA shares more in recent years, since the rise of similar market alternatives. These alternatives meet all the customer desires from the studies listed above and they meet them at a lower price point than CSAs can. Programs like Local Roots NYC and FreshDirect offer high-quality, boxed, organic food delivered direct to the customer that may, or may not, be local (Moskin, 2016). Blue Apron and Hello Fresh take it a step further and offer boxes of food that is pre-measured and ready to cook at home, and they claim to support local farms and “build a better food system” (Blue Apron, 2018).

None of these alternatives to CSAs offer the person-to-person connection that CSAs provide.

That so many alternatives to CSAs have entered the market just goes to show how powerful the CSA idea is. Farmers marketing CSA shares should focus on what makes their CSAs stand out, especially in the flooded urban markets. That means marketing the farmer-customer connection and the community-building that comes naturally through CSA programs.

Advertise

When getting the word out about a CSA, farmers need to hold true to their story. Farm mission, vision and/or values that existed prior to starting a CSA operation are still a crucial part of the messaging. For example, a farm dedicated to affordable produce needs to price its share appropriately.

With all advertising, the medium needs to meet the audience. It may be tempting to run an advertisement in the local paper, but is that the best way to reach a generic young millennial who gets news online? Where will the ideal CSA customer see an advertisement for a CSA share?

The first place many people go for information is the Internet, and any farm looking to advertise its CSA will need to be sure that its potential customers will find it there. This means getting a website, social media accounts, and/or reviews in Google, Yelp, and more. LocalHarvest.com is one of the most utilized CSA listing services on the web. A farmer looking to list a CSA on LocalHarvest.org just needs to sign up for the service. At the time of printing, a listing with space for advertisements was free and an ad-free, paid listing started at $30/year.

When considering where to have a physical presence, CSA farmers should consider where their potential customers are. Health food stores, farmers markets, coffee shops, bookstores, and yoga/wellness centers are all places to consider visual advertisements. Selling product at a farmers market may be a good way to get exposure to potential members. Remember, however, that farmers markets can be a marketing expense, in addition to being a potential source of income. Joining the local Chamber of Commerce, Farm Bureau, Farmers Union, Grange, or other professional organization can also help gain a CSA some publicity.

Word of mouth can be a powerful advertising outlet for a CSA when contented CSA members become promoters of the business. Like all advertising, word of mouth is not free and needs to be cultivated and encouraged. Farmers looking to use their member bases will need to encourage them to become promoters. This encouragement can take the form of anything from a simple acknowledgement to a discount on the next year’s share.

Making a Member Agreement

Having a solid legal footing protects farmers in all sorts of situations. This is especially true for running a CSA, and the most important document involved is the member agreement.

The CSA customer signs a member agreement to become a member or shareholder of the operation. It describes the relationship between the customer and the farmer. This document defines what a share consists of, what the expectations of members/shareholders are, what happens in the event of crop failure, and more. It is also the document that can protect a farmer in the event that a member or shareholder chooses to take legal action. Mostly, the document is an up-front communication tool that gets all involved parties on the same page.

Rachel Armstrong and Laura Fisher of Farm Commons created the free CSA Member Agreement Workbook, which walks farmers through the process of designing a member agreement (Armstrong and Fisher, 2016). It does not replace what a lawyer can do to help create a legal document, but it does help create a good foundation, thus saving a lawyer’s time and the farmer’s money. The workbook also helps farmers make the member agreement that best matches their CSA goals, e.g., what does a share consist of, how simple/complicated the pickup should be, and/or how much risk the farmer wants to share with members.

Armstrong and Fisher suggest that every member agreement consist of, at minimum, these four elements:

- Membership/share options

- How members receive the share

- How the farmer collects payment

- The risk and reward

The workbook also provides a complete checklist for farmers to follow, as well as numerous examples to look through.

Example CSA Member Agreement

From the CSA Member Agreement Workbook by Rachel Armstrong and Laura Fisher (2016), this excerpt is an example of the fictional Lazy River Farm CSA Member Agreement. In this example, the farmer has a traditional CSA model and nothing fancier technologically than a tri-fold brochure. He has three pick-up sites and donates shares that are not picked up to the local food pantry. Members pay by check. The farmer also doesn’t want to pass all of the risk along to his members and wants to be willing to refund their money if a crop fails. He’ll make up the difference with crop insurance.

Lazy River Farm CSA Member Agreement

- I understand that my purchase is eligible for a refund only if I move out of the area or if I experience a personal/financial hardship. Refunds will be prorated. I understand that refunds for reasons of personal preference will impose a hardship on my farmer who has already incurred time and expenses on my behalf. If I wish to cancel for personal preference reasons, I agree to try and recruit a replacement member. The farm will grant refund requests for personal reasons on a discretionary basis.

- I understand that my purchase indicates agreement with some shared risk. If, due to weather, insects, or other event beyond the farm’s control, total share volume will be reduced by half or more over the remainder of the season, according to averages over the past 10 years, I will receive a refund, prorated as to the remainder of the season. I agree that if uncontrollable events reduce the total volume of the produce I would otherwise receive by up to 50%, that I will share in this loss.

- I understand that if the season is especially abundant, I may be given the opportunity to pick certain excess products myself. I know that this offering will be made on specific dates and times, as announced by the farm via email, and that accommodations for specific schedules cannot be made.

- I understand that I must pick up my CSA share from the above location between the hours of 4 p.m. and 7 p.m., and that if I do not do so, my share may be donated to a local food pantry.

- I understand that important communications from the farm will be delivered via email and that opening these emails is my responsibility.

Communicate with Members

Running a CSA is conducting a direct-to-consumer operation. By design, there are no intermediaries and, as such, farmers need to be ready to work and communicate directly with their members. For more information, see the ATTRA publication Direct Marketing.

All farmers running CSAs need to decide for themselves what and how to communicate with their members. One of the most common practices is a regular newsletter that explains what members can expect in the weekly share. Here are examples of other common inclusions in a CSA newsletter:

- Recipes tailored to the products available in the share that week. This little add-on can make a large difference for members, as many surveys show that CSA members value cooking at home. Plenty of cookbooks and online databases exist for farmers looking for recipes to include in their shares.

- Food preservation tips. When a specific crop is plentiful, farmers often provide tips on how to preserve that crop. Suppose a farmer has a bumper crop of cucumbers and members find their CSA shares loaded with more cucumbers than it is possible to eat in a week. In this case, a simple pickle recipe included in the share can help reduce potential food waste and help members see the value in the extra product.

- Inside views into the farm operation. The personalization of a farm operation helps the members feel like they are more than just customers. This can take various forms, from captioned photographs to short essays. This technique can help farmers looking to build strong consumer-farmer connection with their CSA members.

Another common way for CSAs to communicate with their members is to hold events on the farm. A field-to-table dinner held in a greenhouse with farm-sourced food builds community and offers members a chance to interact directly with the farmer. A cautionary note: there are laws governing the safety and sale of prepared food that differ from produce safety laws.

Communication flows in two directions, and farmers need to be ready to receive information from CSA members as well. This could be as simple as always being available on a CSA pick-up day and as complicated as having a digital Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system. Farmers should ask themselves: how will members provide feedback? How will they inform the farmer if they will be missing a week’s pickup? How will they communicate a problem with the product?

Crucial to any business communication is an evaluation process. Many CSAs put out an end-of-season evaluation to their members, such as a survey, to understand if their products meet member desires. As with any evaluation process, a farmer first needs to have a clear business strategy and only ask the questions that pertain to that strategy. Members can easily get “survey fatigue” from too many or too lengthy surveys.

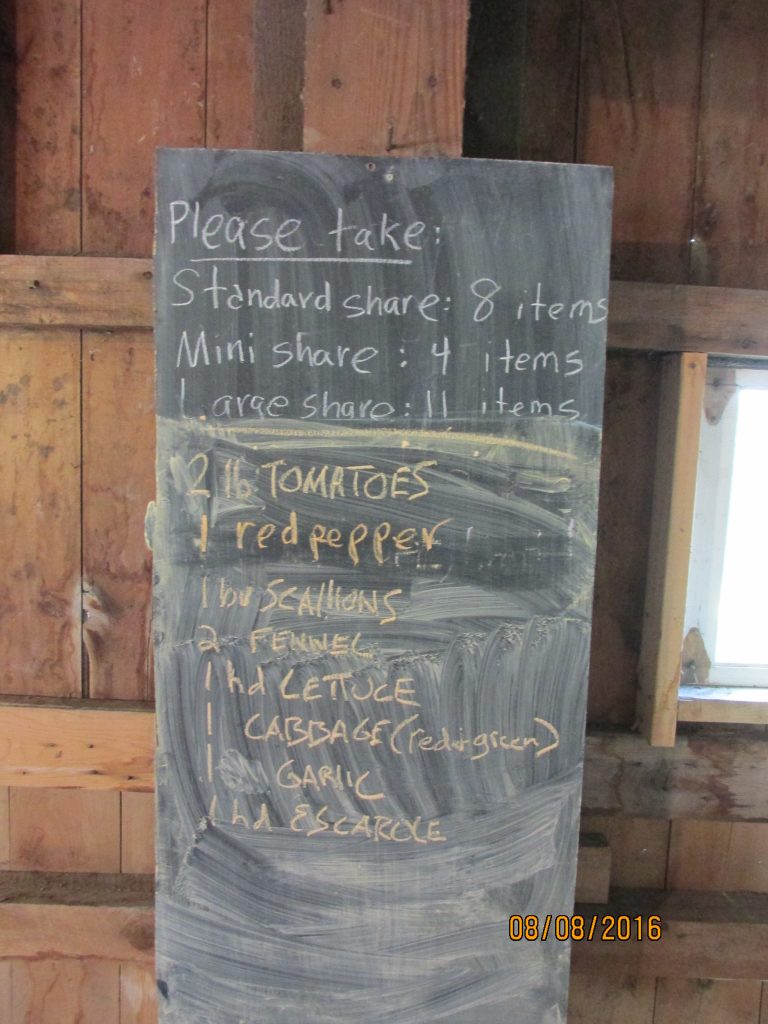

Communication doesn’t always happen at a distance. Common Thread Farm in Hamilton, New York, reminds folks about their shares on a chalkboard at the pickup site. Photo: Andy Pressman, NCAT

Communication doesn’t always happen at a distance. Common Thread Farm in Hamilton, New York, reminds folks about their shares on a chalkboard at the pickup site. Photo: Andy Pressman, NCAT

Related Publications

- Tips for Selling Through CSAs – Community Supported Agriculture

- Direct Marketing

- Market Gardening: A Start Up Guide

- Scheduling Vegetable Plantings for Continuous Harvest

- Season Extension Techniques for Market Gardeners

- Evaluating a Farming Enterprise

- Planning for Profit in Sustainable Farming

- Outreach Tips for Farms that Accept SNAP Payments for CSAs