Hooped Shelters for Hogs

By Lance Gegner, NCAT Agriculture Specialist

Abstract

This publication discusses some of the advantages and disadvantages of using hooped structures for finishing hogs or housing gestating sows. It provides information on hoop barn design, deep bedding, waste management, and minimal-stress handling, as well as some cost analyses. In addition, it discusses the use of hoop barns for organic hog production and for Niman Ranch hog producers. Sources of additional information are also provided.

Introduction

Hoop shelters are an alternative production system for hogs that involves using low-cost greenhouse-like structures and a deep-bedding system different from confinement structures. Hooped shelters are designed to take advantage of the natural behavior of hogs to segregate their sleeping, dunging, and feeding areas. Hoop shelters’ deep bedding helps control hog odors and decreases the risk of manure runoff affecting water quality. Hoop shelters can be used for other purposes when not employed in hog production.

Producing hogs is tougher and more complex today than it once was. The emergence of large confinement operations and other economic factors have contributed to a commercial marketplace in which it is difficult for family-scale operations to remain viable. In response to this competitive environment, hooped shelters have evolved as an alternative, low-cost option producers should consider in their sustainable or organic hog operations.

To be sustainable and/or organic, family farmers may need to return to a more diversified system of farming, using more crop rotations and integrated livestock. Crop rotations refer to the sequence of crops grown on a field. Different crop rotations can affect long- and short-term soil fertility and pest management. Crop rotations may use forage legumes to provide nitrogen needed for other crops. On a diverse, integrated farm, livestock recycle nutrients in manure that is used to grow the livestock feed, forages, legumes, and food crops typical of healthy, diversified cropping systems, and hogs will readily eat weather-damaged crops, crop residues, alternative grains, and forages.

Using crop rotations and animal manures makes diversified farms more ecologically sound and economically stable over the long term. By integrating crop and livestock enterprises, the family farmer may be giving up some of the productivity and profitability achieved with specialization and economies of scale. However, diversified farms can also provide more stable returns by reducing the risks of specialization. As the old saying goes: “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.” Diversification also allows for greater reliance on on-farm resources rather than purchased inputs.

In 2004, there were more than 3000 hooped shelters in Iowa, most used for hog production. Hooped shelters are also used for housing beef and dairy cattle, horses, and sheep, and for storing hay, grain, and machinery. (Miller, 2005) It is important to get any required building permits before putting up a hoop barn. (Anon, 2003)

Some advantages and disadvantages of raising hogs in hooped shelters compared to confinement facilities can be seen in Table 1.

According to the publications Hoop Barns for Grow-Finish Swine(AED-41) and Hoop Barns for Gestating Sows (AED-44), by MidWest Plan Service (see Sources of Additional Information: Publications below), hoop barns are appropriate for

- a farrow-to-finish producer who weans about 150 to 200 pigs at a time and uses outside lots;

- a small, farrow-to-finish producer who wants to improve housing for his breeding stock or finishing hogs by switching from outside lots or Cargill-type floor units to a more manageable environment that allows better runoff control, better feeding efficiency, and better pig observation;

- a producer who is seeking a facility that has alternative uses if the swine enterprise is discontinued; and

- a producer whose goals require a lower capital investment and who has crop-residue-harvesting and solid-manure-handling equipment.

Hooped Shelter Design for Finishing Hogs

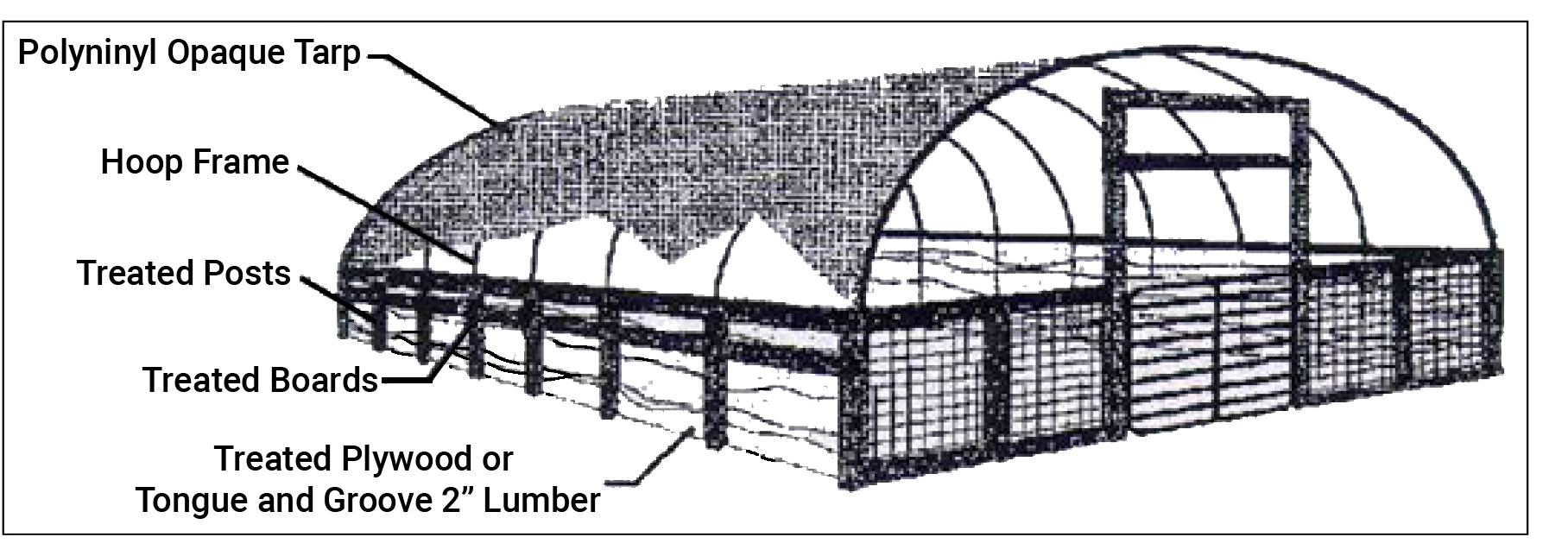

Developed in Canada as alternative housing for hog finishing, hooped shelters are arched metal frames, secured to ground posts and side walls or concrete walls about 4 to 6 feet above ground level, and covered with a polyethylene tarp that is stretched and secured. Some producers recommend using 6-foot side walls to allow better ventilation during the summer and greater ceiling space for cleaning out the manure. (Anon, 2003) It is easy to accidentally tear a hole in the tarp, but the tear can usually be patched with a special polytape available from the shelter manufacturer. Hooped shelters come in various sizes, but a typical size is 30 feet wide by 60 to 80 feet long. At the optimum stocking density of 11 to 12 square feet per hog, the capacity of a 30 by 80-foot shelter is about 200 hogs. (Brumm et al., 2004)

Occasionally, this limited space leads to fighting among the hogs. Some organic and sustainable farmers reduce the stock density to allow 14 to 16 square feet per hog, so that the capacity would be about 160 hogs.

The shelter’s end walls have moveable closings — made with plywood doors, tarps, or other materials — that are left open most of the year for ventilation. Some producers recommend that doors be made of wood or metal on a slide, because canvas doors don’t work well in strong winds. (Anon, 2003) The end walls are adjusted in winter to admit fresh air and reduce humidity levels. Erecting end wall closings can be difficult because the end pipes of the shelters cannot be used for support. (Honeyman, 1998) Many producers have added 16-foot steel hog gates on both ends of the shelter to allow easier entry for regular additions to bedding and for cleaning out manure.

In several northern areas and Canada, shelters are situated on an east-west axis to protect the open ends from prevailing cold winds; however, most shelters are laid out north-south, or a bit northeast by southwest, to catch the prevailing summer breezes. If more than one hoop barn is planned, it is important to maintain a distance between the hoop barns to allow the prevailing winds to circulate through all the barns. (Anon, 2003) A concrete pad (usually on the eastern or southern end) runs the full width of the shelter and is usually extended 16 to 20 feet into the building. The concrete pad holds the feeders and usually two heated or freeze-proof waterers. The pad is typically 6 to 15 inches higher than the rest of the floor and is slightly sloped toward the outside to allow water to run out of the shelter if a problem develops with the waterers. There may be gates and fencing on the inside of the pad to restrict the hogs to several small openings on each end for access to feed and water. This helps to separate the dunging area and sleeping area from the feed and water area.

Small Scale Hoop StructuresResearchers at Iowa State University erected a 14 x 30-foot hoop structure, using large square bales of straw for the foundation. The interior space was 348 sq. feet. The researchers placed 21 138-pound pigs in the hoop and fed them to market weight. The small-scale hoop worked well for the group of pigs, which were in the hoop for 64 days and marketed at 259-pound average. Their average daily gain and feed conversion were consistent with averages for other housing facilities. The researchers noted that at market weight the hoop seemed crowded. Therefore, they recommend more than the standard 12 sq. feet per pig for pigs in hoops—probably about 14 to 16 sq. feet would be better. Also, because of the smaller size, the waterer and feeder took up a larger percentage of the space, and the dunging and sleeping areas became congested. Based on this study, the small-scale hoop structure appears to be a low-cost option that is easy to build. The straw bales lasted about six months, but would have lasted longer in drier conditions. The hoop structure can be disassembled and relocated to a new foundation. (Honeyman and Rossiter, 1999) |

The concrete feeding and watering pad should have a downward curb on the inside edge of at least 12 to 18 inches to help separate the bedding from the feeding area. The rest of the shelter can be either a dirt floor or concrete. In some situations, on sandy soil for example, the dirt floor must be clay-lined to control leaching of nutrients into the ground water. If a dirt floor is used, and pigs have been in the barn for several rotations, the pigs and manure-loading equipment can sometimes undermine the concrete feeding area. If too steep a drop-off develops between the concrete and the dirt floor, it may be necessary to put in narrow concrete ramps to help pigs, especially younger pigs, get to the feeders and waterers on the concrete.

According to the Midwest Plan Service publication Hoop Barns for Grow-Finish Swine, a complete concrete floor will prevent hogs from digging into the dirt floor. It will reduce bedding use in the summer because pigs cannot dig down to the cooler soil. In some states, regulations require concrete floors to prevent nutrients from leaching into the underlying soil and groundwater.

The pigs’ bedding is a deep, slowly composting litter of organic matter, such as straw, corn stalks, hay, etc. It is necessary to maintain a deep bedding pack with a dry sleeping area at all times of the year. The back third of the shelter is generally the dry sleeping area, while the middle third is where the pigs dung. Wetting the area of the barn where the producer wants the pigs to urinate and dung will help train the pigs to use that area. (Anon, 2003) Two-thirds of the shelter’s floor (concrete or dirt) is all deep-bedded. Some manure scraping or removal from the concrete feeding and watering pad may be necessary in certain groups of hogs. If the shelter is equipped with some sort of divider or has a front alleyway to move hogs to, manure can be removed from soiled areas almost any time, using a skid-loader or a tractor loader equipped with a grappling fork or bucket, and a manure spreader.

Feeder pigs are moved to the shelter when they weigh 40 to 65 pounds and are left in the same shelter until they reach market weight. Feeder pigs brought into the shelters during the winter need to be heavier to help them tolerate the stresses of cold and moving. It has been suggested that producers might make “huts” for feeder pigs brought into hoop barns during the winter. The huts would be made of square or round bales with either planking or plastic on top. (Anon, 2003)

Occasionally, problems arise with hooped shelters because of improper management practices, such as not providing enough bedding for the weather conditions or bringing small, unhealthy pigs into a cold building. Deep bedding is key to the shelter’s performance. When in doubt, add more bedding. Even in winter, adequate ventilation must be maintained because of the moisture generated by both the hogs and the bedding pack. Smaller pigs should probably be protected from winds, but heavier hogs need good ventilation. (Anon, 2003) High humidity is an invitation for disaster in hog production.

Agricultural engineer Terry Feldmann of Animal Environment Specialists, Columbus, Ohio, is concerned about some producers’ dedication to manually adjusting ventilation during extreme hot and cold temperature changes, rather than automating the adjustment of the end-wall tarps in a manner similar to curtains in a naturally ventilated confinement building. He suggests that hogs be bedded properly to make ventilation more constant and comfortable, and that a sprinkler system or stirring fan be installed for supplemental cooling in hot weather. (Messenger, 1996) Some hog producers don’t believe that fans are necessary, but suggest strongly that the halfmoon at the top be kept open year round, regardless of the weather. (Anon, 2003)

Various hoop-building manufacturers use different types and strengths of structures or covers. The hooped shelter buyer needs to do comparison shopping and consider the snow load and weather variables in his or her location. The buyer also needs to consider the additional cost of added features, shipping charges, guarantees, and types of tarp coverings.

Construction cost varies with the size and type of shelter. Different types of feeders, waterers, and gates, as well as the amount of concrete (complete concrete floor or 2/3 dirt), influence the total price. Iowa Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering provides listings of Sources of Hoop Structures for Swine. A copy of this list of hoop barn sources can also be requested by contacting Mark Honeyman at Iowa State University (see Sources of Additional Information: Contacts).

Hooped Shelter Design for Gestating Sows

Hooped shelters for sows will be the same basic hoop structure as with finishing hogs, but with different floor designs and additions for better management of gestating sows. The appropriate size of a hoop structure for sows is determined by answering the following questions.

- How many sows in the gestation group are needed for the producer’s farrowing schedule and the size of the farrowing house?

- Where are the boars and gilt pool going to be maintained and managed?

- How are gilts or replacement sows going to be added safely to existing groups of gestating sows without undue stress or fighting?

- How often are the sows going to be fed? Daily or at a two- to three-day interval?

- Are the sows going to be fed in feeding stalls, by self-feeders, or on the floor? This decision will greatly influence the amount of space and concrete needed.

- Are lights going to be needed for night work, such as feeding or various health or pregnancy checks after dark?

- Are extra waterers or a misting system needed for hot summer days to help reduce the harmful effects of heat on breeding efficiency?

How producers answer these questions will influence the size and expense of the hoop structures needed for their situations. Hoop barns used for gestating sows usually provide at least 24 square feet of bedded area per sow. (Harmon et al., 2004) Gestation pen layout will depend on the feeding system, as well as the number of sows in each group. Pens need to be at least 15 feet wide to reduce the bossy sows’ aggression and to allow the more timid sows to pass freely. (Harmon et al., 2004)

The MidWest Plan Service publication Hoop Barns for Gestating Swine and the University of Minnesota’s Alternative Swine Production Systems Program publication Swine Source Book: Alternatives for Pork Producers (see Sources of Additional Information: Publications for ordering information) provide various examples of layouts for different methods of feeding and for different numbers of sows in each group. Other very valuable management tips for working with gestating sows in hooped structures are also provided in these publications.

Deep Bedding

Deep bedding consists of a deep layer of 14 to 18+ inches of materials such as wheat, oat, or barley straw; baled cornstalks; chopped soybean straw; grass hay or CRP hay; ground corn cobs; baled and shredded recycled paper; rice hulls; or a combination of various types of material that will absorb moisture and help keep the pigs dry and warm. Certified organic farmers will need to use certified organic bedding materials to meet organic feed requirements, according to USDA National Organic Program Regulation Section 205.237, because hogs typically root in and eat some of their bedding.

There is no supplemental heat added to hooped shelters with a deep bedding system, so the winter air temperature in the hooped shelter is only about 7 to 10°F warmer than it is outside. (Jannacsh, 1996-7) However, in one study during the winter, with -20°F temperature, a probe placed in the bedding registered nearly 100°F. “When you go into the building on cold mornings, it looks like gators in a swamp,” says Equipment Sales Manager Jim Albinger at the Animal Health Center. “All you see is eyes and ears.” (Houghton, 1997) A Manitoba study found that the microclimate created by the pigs burrowing in straw bedding may reach 68°F at times when outside air temperatures may be -4°F. (Jannacsh, 1996-7) The deep bedding provides some heat to the shelter from the composting of the bedding material and small amounts of manure. However, the area where the pigs sleep should have very little manure mixed in the bedding, since they dung in other areas; probably very little composting will occur in the sleeping area or dunging area until these areas are mixed at clean-out time.

The producer needs to use caution if wood shavings, sawdust, or other wood products are used as bedding material for finishing pigs or gestating sows. The following warning is included in the publications Hoop Barns for Grow-Finish Swine and Hoop Barns for Gestating Swine (see Sources of Additional Information: Publications).

Wood product residue should be used with caution. Shavings and sawdust need to go through a heat cycle to avoid the transmission of avian tuberculosis to the pigs. Unless wood product residue has gone through a heating process, there is a risk of carcass condemnation at slaughter.

Fred Tilstra, a hog producer in Steen, Minnesota, with several hooped hog shelters, stated that straw bedding is best for very young pigs. Cornstalks or bean straw do not provide enough protection with 25- to 32-pound pigs in cold weather. By April or May, almost anything will work, but cold weather demands good straw, and producers should save some for this time of year. (Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture, 1996)

Barley straw was used in several trials conducted during 1992 and 1993 in Canada by the University of Manitoba. Straw required was 194 pounds per pig for the summer trial, 242 pounds for the fall trial, and 363 pounds for the winter trial. (Honeyman, 1998)

When corn stalks are used, each group of finishing pigs takes at least 30 big, round bales of corn-stalk bedding, or more than 75 bales of corn stalk bedding per year. Homer Showman, a Shellsburg, Iowa, pork producer, says, “When I bring in a new batch of 200 pigs, I break up 12 to 15 big, round bales of corn stalks to make a nice, deep nest. I add more bedding as needed. How much depends on the time of the year and weather.” (Otte, 1997)

Recycled paper will make decent bedding material; however, it is most absorbent if it is shredded, and it may not be a very warm material. It should be readily available from recycling centers. A problem with paper bedding is, when spread out on the field, it tends to blow around and may cause problems with neighbors. (Anon, 2003)

Several bedding materials can be used with gestating sows. Corn stalks are probably the most commonly used materials, but small grain straw, prairie hay, wood shavings, and sawdust have also been used (chopped soybean straw tends to be dustier than many other materials, may tend to pack, and doesn’t absorb moisture well). All bedding material should be free of molds to prevent problems during gestation. (Harmon et al., 2004)

Like finishing pigs, gestating sows usually establish certain areas for dunging and sleeping. For example, the sows might sleep in the far back along the wooden sidewalls, and dung in the area between the concrete feeding and watering areas and the sleeping area. Bedding can be adjusted as needed to prevent the dunging area from becoming sloppy. Enough bedding is needed to keep the soil under all the bedding pack relatively dry.

Manure Clean-out and Composting

Between groups of pigs or sows at cleanup time, the producer can use a skid-loader or a tractor loader equipped with a grappling fork or bucket to clean out the shelter in preparation for a new group of pigs. The amount of deep bedding material and manure in a 30 by 80-foot shelter should equal about 15 loads of solid manure hauled in a 185-bushel manure spreader. (Houghton, 1997) The solid manure quality will vary greatly between the sleeping area, where little manure is mixed in, and the dunging area, which will have high levels of manure and urine mixed in the bedding material. The solid manure can either be hauled to the field directly or composted to reduce the amount of material hauled to the field. Bedding from gestating sows usually is much drier than bedding from finishing pigs and may require additional moisture if composted prior to field application. (Harmon et al., 2004)

If the manure is hauled directly to the field, the application rate should be determined by the nutrient content of the manure and the soil and crop needs in the field. This can be accomplished with manure and soil testing. Proper adjustment and calibration of the manure spreading equipment is important to assure accurate application. Nutrient crediting for the manure—taking into account the nutrients contained in the manure when planning fertilization—can lead to significant reductions in fertilizer purchases. The manure application rate is usually based on the nitrogen needs of the crop. But be aware that manures may contain high levels of phosphorus and potassium that could lead to excessive buildup of these nutrients in the soil over several years. The producer can address this potential problem by adjusting the manure application rate to meet the phosphorus needs and using alternative means to supply the additional nitrogen needed. More information on field application of manure is available in ATTRA’s Manures for Organic Crop Production.

Hooped barns and Niman Ranch protocolsNiman Ranch Company—founded by Bill Niman nearly 30 years ago—sells natural meat products over the Internet and on the East and West Coast. Niman Ranch’s 400+ pork producers follow the protocols set by Niman Ranch (Niman Ranch, 2004a) and the Animal Welfare Institute (AWI) Humane Husbandry Criteria for Pigs©. (Niman Ranch, 2004b) Animal Welfare Institute criteria prohibit any split or dual operations and require that all participants be family farmers who depend on the farm for their livelihood and participate in daily physical labor to manage the farm and hogs. The AWI criteria state that after January 1, 2005, any new farmers entering their AWI program, or any farmers already in their program that remodel or build new hog structures, must provide access to outdoors year-round for all breeding animals (except lactating sows and their litters) and for pigs from two weeks after weaning to their market day. The outdoor requirement may be met with either continuous access to pastures, fields, or timber environments, or with outdoor paddocks that allow the pigs to find their own shelter from excessive heat, wind, sun, cold, snow, or rain. AWI feels that access to the outside is an important aspect in the minds of the consumers interested in humane hog production, and it will help differentiate pork produced under their criteria from other pork products. This means that in order to meet AWI’s criteria, all finishing pigs raised in hoop houses need to have about 10 square feet per pig inside, 4 square feet per pig outdoors, and 4 square feet either inside or outside for a total of 18 square feet. This required change of the hoop barn layout to allow outdoor access may undermine some of the benefits of a hooped shelter. It may prove more difficult for farmers to manage the outside area and not radically upset the dunging and sleeping areas in the shelter, reduce the deep-bedded composting system, and compromise the animal-welfare aspects of the hoops. Additionally, any areas opened up to allow pigs access to the outside—whether on concrete or dirt—can rapidly become the pigs’ dunging areas and thereby pose a pollution risk from manure runoff. The manure from this outdoor area will need to be scraped periodically to reduce buildup. The outdoor area will need to have some type of runoff control, such as settling basins, vegetative filters, or holding ponds. It will also be necessary to divert any rainwater or snow melt to prevent it from adding to the runoff. Any runoff from the open-access area will have high levels of pollutants. For more information about becoming a hog producer for the Niman Ranch Company, contact: Niman Ranch Pork Company |

Composting is one way of stabilizing the manure’s nutrient content and reducing the bulk of the material hauled to the field. Composting is a natural process relying on aerobic microbial activity and decomposition. Well-made compost is usually free of weed seeds and pathogens and has virtually no potential to burn plants, regardless of application rate. When applied to the soil, compost increases the soil’s biological activity, improves soil tilth, and increases the availability of certain plant nutrients already in the soil. Compost also contains nutrients that are more readily available to the plants and are held against loss through leaching and volatilization.

Almost any organic material can be composted if the proper C:N ratio, moisture content, and aeration are maintained. However, making good compost is an art as well as a science. Compost, like manure and soil, should also be analyzed by a laboratory to ensure nutrient value. On-farm composting will require additional labor and management, as well as additional equipment for turning the compost.

Organic Certification and Hoop Shelter HogsAfter more than a decade of work by organic growers, processors, supporters, and the USDA, the National Organic Program (NOP) went into effect on October 22, 2002. The regulations provide specific standards that growers must meet to be certified organic. While the standards for organic production of crops have been evolving since the 1970s, organic meat was not even given official USDA recognition until 1999. NOP regulations include some specific requirements for living and housing conditions for livestock. Section 205.239(a)(1) requires producers to provide animals with “access to the outdoors, shade, shelter, exercise areas, fresh air and direct sunlight suitable to species, its stage of production, the climate and the environment.” Section 205.239(a)(4) requires that the shelter be designed to allow for “natural maintenance, comfort behaviors, and opportunity to exercise; temperature level, ventilation and air circulation suitable to the species; and reduction of potential for livestock injury.” These regulations are meant to ensure that hogs have access to natural conditions and an opportunity to engage in some of the instinctive behaviors—such as rooting, socializing, and foraging—that are essential to their health and welfare. The regulations effectively discourage confinement production. However, Section 205.239 (b) of the NOP does allow the producer to provide temporary confinement due to “inclement weather; the animal’s stage of production; conditions under which the health, safety or well-being of the animals could be jeopardized; or risk to soil or water quality.” The NOP requires organic hog producers to have finishing systems that reduce or minimize stress. Which finishing options are approved will depend on how the NOP regulations are interpreted by the various certifiers, especially concerning access to the outdoors, shade, shelter, exercise areas, fresh air, and direct sunlight. Certification decisions will be influenced by the specifics of the farm’s organic system plan—the detailed outline that explains how the producer intends to satisfy the requirements of the NOP regulations. Hooped shelters have all the appearance of a promising system for organic hog finishing. They give hogs an opportunity to engage in their instinctive social behavior, while rooting and foraging in their deep-bedded shelter. They also provide the opportunity for exercise and for the hogs to nest in the composting deep bedding and individually control their own temperature and environment. The hooped shelter is designed for good natural ventilation and protection from elemental extremes. According to an Iowa State University study, “Pigs in the hoop were adjudged to have enhanced welfare as compared to pigs raised in the non-bedded confinement system.” The Animal Welfare Institute, the American Humane Association, and the Humane Society of the United States have all approved hooped shelters, with their deep, organic bedding, as welfare-friendly. When a group of hoop-sheltered hogs is marketed, the manure and bedding removed from the shelter can be either composted or applied directly to fields in a manner that reduces the risk of any soil or water contamination. This bedding and manure have been protected from rain and snow, reducing the potential for any water or soil pollution. In these ways, hooped shelters address the requirements of Section 205.239(c), that manure be managed “in a manner that does not contribute to contamination of crops, soil or water by plant nutrients, heavy metals or pathogenic organisms and optimizes recycling of nutrients.” The problem with hooped shelters—and the reason producers need to work with their certifiers —is the lack of outdoor access. Deep-bedded hoop shelters were originally designed and tested without allowing the pigs outdoor access, even though both ends of the barn are open and allow shade, shelter, exercise areas, fresh air and direct sunlight. Hooped barns demonstrate an effective arrangement of areas for dunging, bedding, rooting, and socializing in a self-contained unit that fosters instinctive behaviors and mimics the hogs’ natural environment. A hooped shelter mimics the shade and canopy of the forest environment where hogs originated. Hogs have poor heat regulation systems, because of their inability to sweat, except through their mouths, and their thin hair cover, which can result in sunburn, especially behind their ears. Pigs need protection from the sun during the summer, and they need bedding materials during the winter to help protect them from the cold. Organic hog producers wanting to use hooped shelters should make a case for hooped shelters in their organic system plan. Transitioning and certified producers will need to present a convincing argument for the year-long use of hooped shelters and explain why the system is necessary and desirable before constructing the hooped shelters. Seasonal use will be an easy sell, because the NOP regulations specifically allow confinement during inclement weather, both to keep hogs safe and to reduce risk to soil or water quality. Possible points to emphasize for year-long use include:

Producers may need to provide support and documentation for the use of hooped shelters from various sources, such as historical data, research or educational documentation, and/or the producers’ personal experiences with hooped shelters. They will need to show how the use of hooped shelters fits into the entire livestock and/or cropping system on the farm and how they will help reduce manure runoff and help meet the Environmental Protection Agency Animal Feeding Operation requirements. Based on its review of the organic system plan, the certifying agency will decide whether the producer’s use of hooped shelters complies with the NOP regulations. Currently, the largest national organic pork supply comes from CROPP (the Cooperative Regions of Organic Producer Pools) Cooperative. CROPP Cooperative is an added-value marketing cooperative comprised of 750 family farms in 22 states. All of the non-meat products are marketed under the well-known brand label Organic Valley and the meat products are marketed under the brand label Organic Prairie label. CROPP’s organic hog production standards allow the use of hoop buildings as long as the hogs have access to fresh air and sunlight. Organic hog production standards for CROPP follow at a minimum the National Organic Standards and also include production measures such as no tail docking and a minimum of 48 square feet for farrowing sows. For more information about CROPP Cooperative’s production standards, you can go to their website or contact the CROPP Membership Services at 888-809-9297. The CROPP standards are intended to be consistent with the requirements of the National Organic Program. However, because the regulations are not specific, certifiers will be more or less liberal in interpreting them. Because there can be changes to the rules and regulations, it is important for producers to keep in contact with their certifiers and stay current with any changes that will affect their organic certification. |

In comparison studies, hogs finished in hooped shelters consistently ate more, grew faster, and had a feed efficiency advantage when compared to hogs in Cargill-style buildings and remodeled conventional barns with outdoor feeding and watering platforms. However, most likely due to the increased feed intake, the hooped shelter hogs tended to average about 0.19 inches more back fat on a carcass merit program. (Houghton, 1997) Feed efficiency can depend on the season of the year, the overall health status of the pigs, and/or the energy and protein level of the ingredients of the ration.

In a 2001 North Dakota study, the net return per hog was $33.19 for hoop-raised hogs, $31.84 for confinement raised, and $30.99 for outdoor pen raised. Evaluation parameters included turns/year, facility investment, fixed costs, operating costs, total carcass value after premiums and discounts were applied, and net returns per pig for each system after total cost of the pig was deduced from total carcass value. (Landblom et al., 2001)

In a two-year trial that combined both winter and summer production of finishing pigs in hooped and confinement facilities, the study showed that the pigs in the hoops ate more feed, grew faster, and required more feed per unit of live-weight gain than confinement pigs. Between the two systems, the mortality rate was equal, but the percentage of culls was higher in the hoops. The hoop pigs were fatter in the summer and less efficient in the winter. The hoop pigs had greater incidence of roundworm infestation, despite a thorough deworming regimen. The stocking density for the hoops was 12 square feet per pig and 8 square feet for confinement. Each hoop was designated a pen. The hoop structures were 30 x 60 feet, with 150 pigs per hoop. The confinement slatted-floor pens were 13.5 x 13 feet, with 22 pigs per pen. (Honeyman et al., 2000)

In an Iowa State University economic study, the researchers separated the summer and winter feeding trials when comparing the economics of finishing pigs in hoop structures or confinement. The studies are based on fixed cost per pig space: $180 for confinement finishing vs. $55 for hooped barn, with 2.6 hog cycles per year. While total fixed cost per pig per year of about $11.50 for confinement is nearly double that for the hoop, total overall operating costs favor confinement by nearly $3.50/head during the winter, but favor the hoop system by $.50/head during the summer. These studies are consistent with other studies that also show hoops require higher operating costs for bedding and feed when compared to confinement. (Larson et al., 2000)

Even though the total labor requirements are about the same, the producer will need to consider the management differences between hooped shelters and confinement houses or other types of finishing houses. Successful operations in a shelter will require management of ventilation, bedding, feeders, waterers, and pigs, and scraping the concrete pad when necessary. Keep in mind that this is a deep-bedding system, and supplying bedding to the pigs in the shelter can be a time-consuming chore. (Jannacsh, 1996-7) Bedding and manure removal and spreading can take 12 to 15 hours after each group of pigs. (Honeyman, 1998) In winter, removing the old, composting manure right before bringing in the group of feeder pigs, rather than after the group is marketed, may help keep the dirt floor from freezing and causing the shelter to become too cold.

Several problems have been encountered with hooped shelters because of improper management practices, such as skimping on bedding (not providing enough bedding for the weather conditions) or by bringing pigs that are unhealthy or too small into a cold building. Again, deep bedding is key to shelter performance. A cardinal rule for operating the shelter is “when in doubt, add bedding.” (Houghton, 1997)

John Ikerd, Professor Emeritus, University of Missouri, Columbia, presenting at the Food and Society Networking Conference at Olympic Valley, California, commented:

The bottom line of all these comparisons is the economic efficiency is not significantly different among confinement, hoop house, and pasture based systems of hog production. Individual management ability has a far greater impact on efficiency and profitability than does the type of system. These facts are rarely contested among those who are familiar with cost of production data for various types of hog production systems. (Ikerd, 2004)

Cost Analysis for Gestating Sows

Sow gestation facility costs will vary for each hoop structure, depending on the number of sows per pen per gestation cycle, the type of feeding system (feeding stalls and elevated platforms cost more), and the number of gestation cycles per year (two cycles per pen will have a larger per-sow cost than three cycles per pen). In the MidWest Plan Service’s Hoop Barns for Gestating Swine, the authors calculate the hoop structure’s initial cost at $11,500 for the basic unit, and $19,500 for the basic unit with feeding stalls. They also provide a cost analysis table to help producers calculate their gestation cost per sow. Bedding and cleaning costs must also be figured into the annual cost per sow. These will vary with the type of bedding and the number of gestation cycles between cleanings. Feed cost is another variable; however, with feeding stalls the amount of feed per sow can be reduced by 4.5% because feeding of each individual sow is more precise.

A sow and her piglets. Photo: Keith Weller, USDA ARS

Working Pigs with Minimal Stress

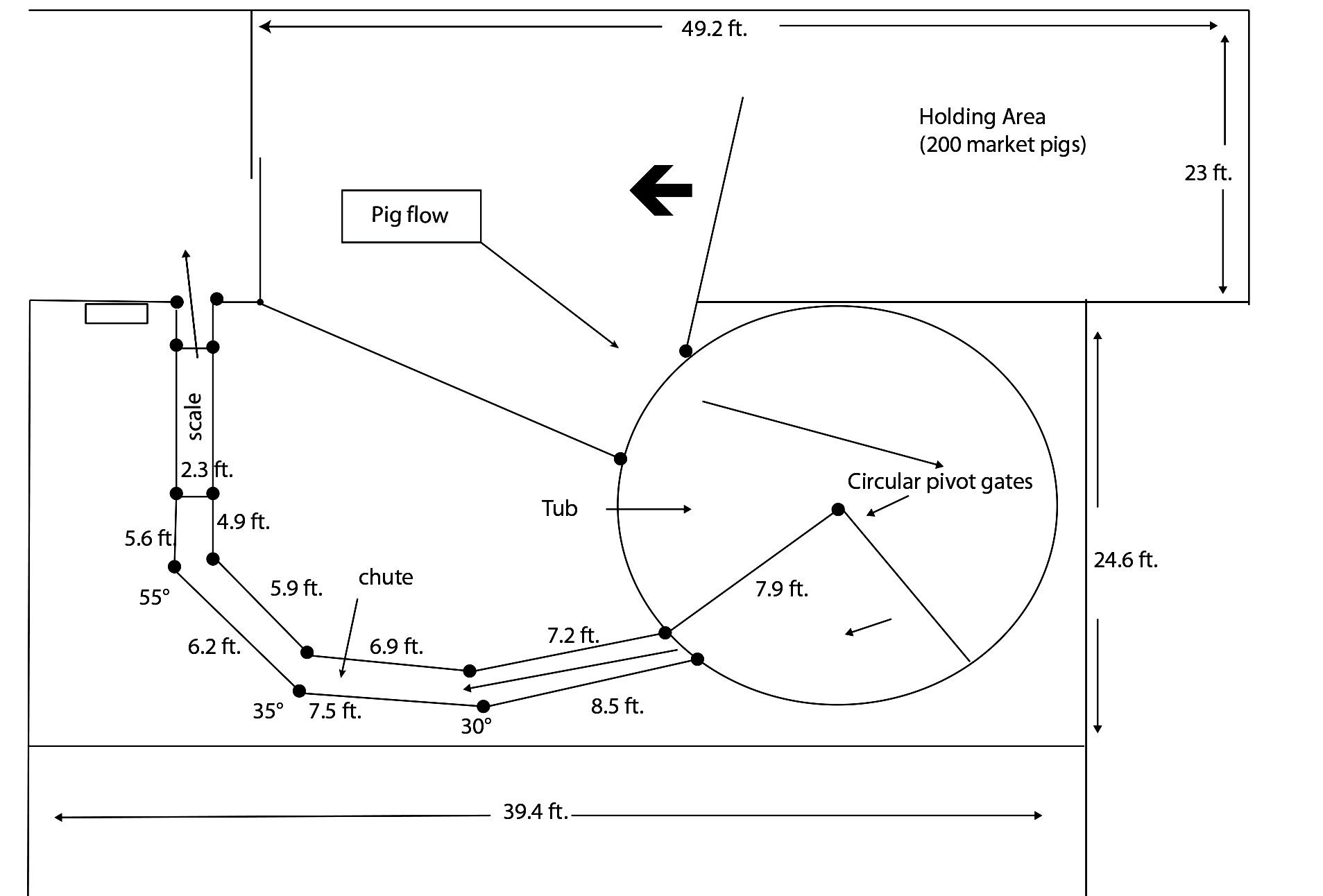

The concrete feeding and watering pad can be used to sort and handle the pigs if an outside fenced area, sorting yard, or other handling facility is not available. The scale, loading ramp, and gates can be installed along a side of the concrete pad in the shelter. Producers can use removable poles with plywood or some sort of gating material to divide the bedded area into two sections. The hogs are confined to one section and then worked in small groups over the concrete pad. After weighing, the pigs are either loaded for marketing or run back into the other section of the bedded area.

The University of Minnesota’s West Central Research and Outreach Center (WCROC) has developed a handling and sorting system for pigs raised in large groups in deep-litter. The system was designed to minimize stress to the pigs and to the people sorting, to reduce the number of people required to handle and sort the hogs, and to develop a system that was economically viable for the producer.

Designer of livestock handling facilities and an Associate Professor of Animal Science at Colorado State University, Temple Grandin, has prepared the following list of 12 tips to help with the sorting and loading of finishing pigs. When loading, move small groups of five to six finishing hogs at a time.

- Don’t hold large groups of finishing hogs in the alley or holding pen; this can lead to damage to the pen because of pigs fighting. It is best to take each small group of pigs immediately from pen to truck.

- Finishing barns should have a 3-foot wide alley to allow 2 hogs to walk side-by-side. If there is only a 2-foot wide alley, only 3 hogs should be moved at a time.

- Do not overload trucks. During hot weather, high death losses can result from overloading.

- Do not allow hogs to stand in a fully loaded truck; get moving immediately. Pigs’ body heat can build up rapidly in stationary trucks.

- Use bedding in trucks during winter hauling to help prevent frostbite on hogs at the packing plant. Straw provides the best insulation during extremely cold weather.

- During periods of high heat and humidity, it is best to transport pigs very early in the morning or at night. Truck density should be reduced.

- Schedule truck loading so that the pigs are unloaded promptly at the packing plant.

- Avoid use of electric prods. They should not be used in finishing barns.

- Try not to excite the hogs; calm pigs sort and separate easier. Handlers should move slowly and deliberately and separate pigs from the group on the first attempt.

- Pigs may refuse to leave a building if air is blowing in their faces as they exit the finishing barn. Shutting off ventilation or reversing it might help.

- For better pig flow out of finishing barns, attach plywood to the last 16 feet of pen nearest the exit door. This prevents pigs from seeing and touching pigs in the pen near the exit door. Remove plywood after loading to prevent interference with ventilation through pens.

View this complete article, Handling Pigs for Optimum Performance on the Farm and in the Slaughter Plant.

Top view drawing of swine handling and sorting facility at WCROC. Adapted from Morrison, Rebecca, and Lee Johnson. 2003. Handling and Sorting Pigs in Large Groups Housed in Deep-Litter Systems. Presented at the Second International Symposium on Swine Housing held in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, on October 12-15. 6 p.

Grandin also makes the following recommendations to minimize the stress level of the pigs being moved or sorted.

- If pigs balk or refuse to move, find out why and remove the distraction. Pigs have wide-angle vision (in excess of 300 degrees) and are easily frightened by shadows or motion. Pigs will balk at crossing a drain grate, hose, puddle, shadow, or change in flooring surface or texture. Pigs have color perception and will even balk at a sudden change in color, so handling facilities should all be of uniform color. Pigs also have a tendency to move from dimly lit areas to more brightly-lit areas, provided that the light is not glaring in their eyes.

- Lightweight plastic or plywood panels, canvas slappers, plastic paddles, or flags made from lightweight plastic work well to move pigs. Avoid hitting the pigs. Solid panels are useful for blocking escape attempts because they block the vision of the pig.

- Avoid excessive noise or shouting; calm pigs are easier to move, while excited pigs bunch together and are harder to sort or move. Pigs have sensitive hearing. Continual playing of a radio with a variety of talk and music helps reduce the reaction of pigs to sudden noises.

Grandin has designed handling facilities that help to reduce the stress on the hogs, as well the people doing the sorting. Some of her suggestions for hog handling facilities include

- having crowd pens with an abrupt or offset entrance (pigs jam in a funnel shape);

- not having any ramps or inclines in the crowd pens, but only after the pigs are in the single file or double chute;

- not curving a raceway unless the pig can see at least three body lengths up the raceway before it actually curves;

- designing a pig-loading ramp so that the pigs are lined up single-file before they leave the sorting area; and

- using a doublewide chute with a see-through middle partition and solid outside walls.

For more specifics on designing a reduced-stress hog handling facility, see the diagrams of Grandin’s recommended designs.

Another option for low-stress sorting of market or finishing hogs is using automatic sorters. Automatic sorters are designed to sort pigs in a large pen environment, such as hoop structures, without supervision. Automatic sorters use an open design that places a scale and alleyway between the pigs and their water and feed. The pigs walk over the scale and are automatically sorted by their weight. Pigs ready for market are directed into a pen, while the others continue to remain in their large environment. For automatic sorter information, please see Sources of Additional Information: Automatic Sorting Contacts.

Conclusion

Hooped shelters are an option that should be considered for family hog production. Because of their recent development, hooped shelters for finishing hogs and gestating sows are not fully tested in all operating situations and may need to be tested more fully to show their reliability and durability. However, when the farmer compares the hooped shelter to confinement finishing or gestating, the building and equipment fixed costs are reduced and financial risks are lower. In the hooped shelters, the feed conversion ratio for finishing hogs is reduced during the winter, and the hogs tend to average somewhat more back fat at slaughter in a hooped shelter. Large quantities of low-cost bedding materials are needed year round, and bedding and manure handling becomes time-consuming. But by converting the manure from a waste product to a fertilizer replacement or supplement, the farmer can save money on fertilizer expenses.

Finishing or gestating hogs in a hooped shelter may not be practical or cost effective for everyone, but it is a viable alternative for many hog producers to consider, and a valuable addition to a diversified farm.

Further Resources

Iowa State University Research and Demonstration Farms

103 Curtiss Hall

Iowa State University

Ames, IA 50011-1050

Phone: 515-294-5045

Fax: 515-294-6210

University of Minnesota West Central Research and Outreach Center, Swine Housing

West Central Research and Outreach Center

46352 State Hwy 329

Morris, MN 56267

Automatic Sorting Contacts

Chore-Time’s Hog Management System

Publications

Iowa State University MidWest PlanService publications

- Hoop Barns for Grow-Finish Swine, Revised (AED-41) 24 p.

- Hoop Barns for Gestating Swine, Revised (AED-44) 20 p.

- Alternative Systems of Farrowing in Cold Weather, (AED-47) 12 p.

- Hoop Barns for Beef Cattle, (AED-50) 16 p.

- Hoop Barns for Dairy Cattle, (AED-51) 16 p.

- Hoop Barns for Horses, Sheep, Ratites, and Multiple Utilization, (AED-52) 8 p.

These six publications discuss hoop shelter use for raising a specific type of livestock. Sections in each bulletin include basic questions, when to consider hoops, designing and erecting the structure, animal handling and management, environment and ventilation, structure management, feeding and watering equipment, bedding, manure handling, sample layouts, comparisons and analyses (cost, labor, financial, research), and other resources.

University of Minnesota Extension Distribution Center Publications

- Swine Source Book: Alternatives for Pork Producers. 1999. By Wayne Martin. PC-07289.

- Hogs Your Way: Choosing a Hog Production System in the Upper Midwest. 2001. By Paul Bergh. BU-07641. 88 p.

Websites

Iowa State University’s Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering

University of Minnesota, West Central Research and Outreach Center, Morris, Minnesota

Have listings of their research projects evaluating hoop and confinement swine production systems for nutrition, behavior, welfare, husbandry, profitability, environmental quality, and social impacts.

Practical Farmers of Iowa

Have five PowerPoint presentations on managing manure and bedding from hoop houses, and a photo journal on building a hoop house.

Minnesota Institute for Sustainable Agriculture’s Alternative Swine Production Systems Program

Website has all On-Farm Demonstration Project reports from the 1999 to 2004 Minnesota’s Greenbook dealing with hoop barns.

Hooped Shelters for Hogs

By Lance Gegner, NCAT Program Specialist

IP149

This publication is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. ATTRA.NCAT.ORG.