Overgrazing – A Chronic Soil Disturbance on Grazing Lands: Part I

Print This Post

Print This Post

By Justin Morris, Regenerative Grazing Specialist

Chronic human diseases are everywhere these days it seems. From diabetes to cancer to heart disease to mental illnesses, our society is plagued by medical conditions that begin nearly unnoticed through a constant, non-intense disturbance, until a serious life-altering condition develops that often has no known cure. This contrasts sharply with acute medical conditions like a broken arm, for instance, that usually happens abruptly but is usually mended and healed quite rapidly.

Interestingly, there are some similarities between how our bodies respond to acute and chronic disturbances and how grazing lands respond to acute and chronic disturbances that come in the form of grazing, drought, fire, hail and even insect pest invasion. Right now, we’ll just focus on the impact of overgrazing and how it’s a chronic soil disturbance on grazing lands.

What is Disturbance?

When discussing one of the five principles of soil health which is minimize disturbance, it’s easy to think that all disturbances are negative. After all, why would we want to minimize something that was good? Are all disturbances to the soil ecosystem detrimental or, if there is such a thing as a beneficial disturbance, what are the characteristics of those disturbances and how can they be used to improve soil health? To answer these questions, we first need to understand what disturbance is.

In ecological terms, a disturbance is a temporary disruption in the environment resulting from natural or human activities that causes a pronounced change in an ecosystem. Notice in this definition that pronounced change to an ecosystem is change neutral, meaning that change can be either positive or negative, depending on the nature of the disturbance. The nature of any disturbance has at least seven dimensions. They include:

Timing – when a disturbance occurs

Duration – how long a disturbance lasts

Frequency – how often a disturbance occurs over a specified time period; frequency when combined with the dimension of duration defines the length of the recovery period between the end of one disturbance and the beginning of the next disturbance

Intensity – the strength of the disturbance force

Pattern – the level of patchiness or uniformity of a disturbance over a geographical area

Size of Disturbed Patches

Scale

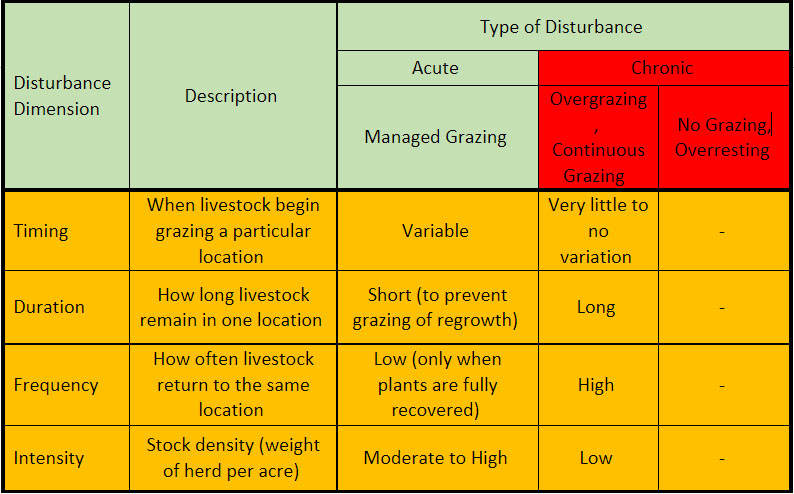

Figure 1: The seven dimensions of disturbance. The dimensions in yellow letters have the greatest impact on individual fields.

For grazing lands, the primary disturbance comes in the form of the interaction between livestock and their landscape through grazing. While there are examples galore of landscapes degraded by uncontrolled or poorly managed grazing, there are also examples of proper grazing management dramatically improving plant and soil health. How could the disturbance of grazing yield such dramatically different outcomes? The reason lies in the difference of the dimensions of the dimensions of timing, duration, frequency, and intensity of grazing as influenced by grazing management. These four dimensions are the primary drivers for improving soil health on grazing lands on a field-by-field basis.

Figure 2: This table shows the relationship between a disturbance dimension and the type of disturbance, whether acute or chronic as influenced by grazing management. Note the near opposite nature for each of the dimensions when comparing acute and chronic columns. No values are given for the far-right column since livestock are excluded from the ecosystem.

As seen in the table above, grazing can be either an acute disturbance or a chronic disturbance depending on the type of management imposed, which directly affects each of the four disturbance dimensions. The interaction of these four dimensions is what determines whether grazing will be a positive or negative for the ecosystem.

Related Resources:

Livestock and Pasture Management

Pasture, Rangeland, and Adaptive Grazing

Why Intensive Grazing on Irrigated Pastures?

The Impact of Grazing Frequency and Recovery Period on Plant Diversity and Soil Health

This blog is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. ATTRA.NCAT.ORG.

CanvaPro

CanvaPro