Agrihoods: Development-Supported Agriculture

By Jeff Birkby, NCAT Smart Growth Specialist

This publication introduces the concept of development-supported agriculture, also known as agrihoods. The recent growth of agrihoods in the United States is discussed. The major types of agrihoods are described, and the benefits and challenges of agrihood development are discussed. Case studies of agrihoods are presented, and further agrihood resources are included.

What are Agrihoods?

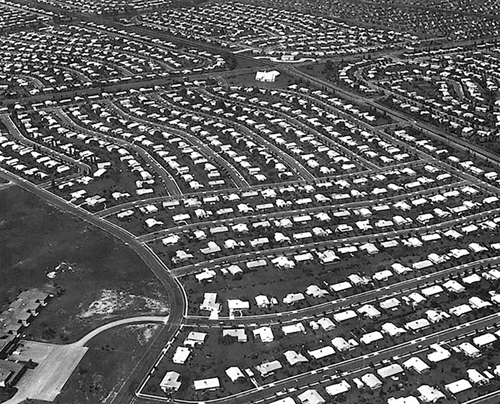

Levittown subdivision in the 1950s. Photo: Wiki Commons

The popularity of planned suburban home developments in the United States stretches back to the 1950s. Many soldiers returning from World War II were anxious to acquire a home and start a family, and the GI bill provided low-interest loans that helped kickstart the post-war housing boom. Many post-war subdivisions consisted of identical home designs packed within cul-de-sacs and along broad streets, often located far from a city center. Levittown, built between 1947 and 1951in the state of New York, epitomized this type of subdivision. More than 17,000 homes filled the Levittown subdivision by the early 1950s.

Although this type of mass-produced subdivision has been popular for decades, residents of these cookie-cutter housing developments often felt isolated from their neighbors due to the subdivision design and lack of central gathering places and walkable streets. But in the 21st century, many millennials, baby boomers, and retirees are seeking out neighborhoods that have more direct relationship to the land and to local food. An increasingly popular subdivision design, called an agrihood, is helping to fill this desire to connect more closely with their community, with nature, and with their food supply.

Unlike the thousands of golf-course developments in the nation, where homes are built around a central golf course and club house, an agrihood is built around a working farm, with much of the land preserved for growing food or set aside in conservation easements.

Golf course subdivisions, popular in the 1960s, were built around a clubhouse and golfing greens. Photo: Wiki Commons

In some agrihoods, the homeowners surrounding the working farm own shares in the farm, and can choose to be actively involved in the planting and harvesting of crops if they desire. The agrihood residents may also hire a farm manager to live onsite and manage the day-to-day operation. More officially called development-supported agriculture, the agrihood concept is fairly new to suburban developers. A few community-owned farmsteads were built in the past 20 years or so (Serenbe, just outside Atlanta, was established in 2005; and Prairie Crossing, outside Chicago, was developed in 1995). But the real growth in agrihoods has occurred in the past decade. Interest and growth in agrihood developments has been dramatic. Ed McMahon of the Urban Land Institute estimates that, as of 2014, there are over 200 agrihoods either developed or in the planning stages in the United States (McColl, 2015).

Types of Agrihoods

Agrihoods typically feature a central working farm, which can include livestock, orchards, vineyards, and row crops. Agrihoods can vary dramatically in total acreage, number of home sites, and farm size.

The smallest agrihoods are sometimes called microhoods, which consist of less than a dozen homes that surround a large community garden or small farm. The residents of these small agrihoods may be much more active in farm management than larger agrihoods, with residents choosing what crops to plant and how to market the produce.

The most common agrihoods in the United States range in size from 100 to 1,000 home units, with a significant portion of land set aside for the working farm and protected areas. In many cases, these agrihoods are built around farms that have been in the same family for generations, and the farm family is behind the development.

At the largest end of the agrihood spectrum are new development-supported agriculture projects that may contain several thousand homes and have hundreds of acres set aside for farming or land conservation. A large agrihood currently under construction near Orlando, Florida, called Lake Pickett South, will contain almost 3,000 homes. This agrihood, which will cost about $1 billion to complete, will feature a 9-acre farm, almost 20 acres of community gardens, and a farm-to-table restaurant. The developer estimates it will take about 20 years to fully build out the agrihood.

Agrihood developers also target different income and age clientele in their home developments and locations. In some cases, high-end homes are the norm, with million-dollar homes common, such as the Kukui’ula agrihood development in Hawaii. On the other end of the spectrum, some agrihoods target low-income and senior citizens, as well as mixed-generation developments. The Win6 development near Santa Clara California is an example of an agrihood that consciously targets a percentage of its homes for low-income and senior citizen residents.

Infill Development and Agrihoods

Infill development (using previously developed commercial land within an urban boundary) is often preferred over developing open space or agricultural land. But many of the agrihoods in the United States are based around existing rural farms on the outskirts of urban areas. However, some developers and city planners are viewing agrihoods as an option for infill development, using land available near abandoned malls, shuttered factories, and demolished housing projects.

Two examples of infill agrihoods are described below.

Infill Example 1: The Cannery

One of the first agrihoods to make use an abandoned commercial facility is the Cannery, located near Davis, California. Concrete covering the site of the abandoned Hunt-Wesson tomato-processing facility was removed, and the soil underneath was used to create a new farm-centered subdivision. (Hickman, 2015)

Opened in late 2015, the 100-acre development will eventually feature over 500 new homes surrounding a 7.4-acre working farm. Almost five acres of public parks and other open space will give community residents room for recreation. The Cannery’s working farm will be managed by the nonprofit Center for Land-Based Learning, which will also manage an educational facility for beginning farmers.

Sustainable design will be used in all residential homes built in the Cannery, including solar photovoltaic systems on the rooftops, tankless water heaters, energy-efficient design, and aging-in-place features for senior citizens. Home buyers can also choose to increase the energy features in the homes to achieve a net -zero- energy status, requiring no net energy to heat, cool, and light the home. A commerce district and town center is planned for retail and small business office space (McGrath, 2015).

Infill Example 2: Win6 Village

Santa Clara, California, is the site of a new 6-acre infill agrihood near a busy thoroughfare. Located near two large shopping centers, the Win6 project will feature a small organic farm as well as community and children’s gardens. Other features include more than 150 housing units designated for low-income or senior housing. Walkable design will be incorporated, allowing residents to easily travel to nearby malls for shopping. Construction on the Win6 development is scheduled to start in January 2017. (Herron, 2015)

The Win6 agrihood in downtown Santa Clara, California, will feature low-income housing. Source: Davis Studio Architecture + Design

Benefits of Agrihoods

The rise of agrihoods in the United States is linked to a variety of benefits available to developers, farmers, and residents. Many of these benefits are tangible, but some are psychological.

Perhaps the greatest attraction for land developers considering agrihoods are much lower development costs compared to similar amenity-centered subdivisions. Over 16,000 golf communities have been built in the nation since the 1960s. These communities usually provided developers with a nice profit premium when compared to standard subdivisions without the golf-course amenity.

It’s easy to see why many developers have changed their mindset from a golf-course centered development to agrihoods, centered on a working farm. “[Developers] figured out they could charge a lot premium [of] anywhere from 15 to 25 percent, [for golf-centered subdivisions],” says Ed McMahon of the Urban Land Institute. “But ironically what we have come to learn over time is the vast majority of buyers in a golf course development actually don’t play golf. A light bulb went off in the mind of savvy developers who said ‘Jeez, I can build a golf course development without the golf course.’ What does it cost to leave the open space alone in the first place? Almost nothing. So that led to designing communities around other green-space amenities such as a farm.” (Esposito, 2014)

A development company sometimes purchases an existing farm outright as the centerpiece for an agrihood, or may also develop new farm infrastructure from the ground up. These costs, though significant, can be less than one-fifth of the costs of developing and maintaining a professionally-designed golf course. And the consumer demand for housing in new agrihoods is tremendous. It’s little wonder why developers are increasingly attracted to the agrihood model.

Developers have also noticed a decrease in interest among millennials in moving to golf-course communities, while the interest in living in a community surrounding a working farm is much more appealing to this generation.

In addition to cheaper development costs, an agrihood can provide a variety of tax benefits to developers for preserving green space and keeping agricultural land in productivity. Some agrihoods have been built on infill space or rehabilitated industrial brownfields, and a variety of tax credits and other financial incentives are available to developers for using this disturbed land.

Finally, developers of agrihoods enjoy the vibrant community feel that takes root. “People who buy homes are looking for community,” says Joseph E. Johnston, developer and resident of Agritopia, which is on farmland his family has owned and worked since 1960. “It’s people and the relationships they have—that’s really community. . . Most developers I’ve seen are in the business of selling homes. We are in the business of creating community.” (Donnally, 2015)

Benefits of Agrihoods for Farmers

Since most agrihoods are based around a working farm, they can also provide steady jobs to the farm managers. Given the low income typically earned by many farmers (especially beginning farmers), the benefits of working at an agrihood can be significant. USDA’s most recent agricultural census estimates that 57 percent of America’s farms gross less than $10,000 a year (USDA, 2014). That means more than half of all farmers in America have to rely on second, and sometimes third, jobs off the farm to cover living expenses.

Farmers harvesting vegetables at Willowsford Farm. Photo: Deborah Dramby

Often an agrihood will hire a farm manager and pay a much higher salary than the farmer could make managing his own land. And agrihoods can provide a great first job to beginning farmers who can’t afford their own land but are willing to work on the agrihood in exchange for a steady salary and great experience. Besides the salary, the farmer and his or her family are often provided with free housing on the farm, which is a major benefit. And farmers living on-site are better able to handle farm chores and deal with farm management issues than someone living further away from the farm.

Farmers in nearby areas can also benefit from an agrihood, since agrihoods often serve as an agricultural educational center. Farmers in surrounding areas are invited to participate in workshops and field days at the agrihood, with topics ranging from beginning farmer issues to marketing organic produce. The local agricultural community may also interact with agrihood residents during these workshops. Agrihoods often serve as a nexus for weekend farmers markets, which may attract surrounding farmers who sell their local produce to agrihood residents.

Benefits of Agrihoods to Residents

Agrihoods provide major financial benefits for developers and farmers, but the major driving force behind the growth in agrihoods may be the desires of homeowners to be closer to nature and to experience the community that develops around a working farm. According to Brent Herrington, who directed the development of the Kukui’ula agrihood in Hawaii, “A community farm is a welcome respite from the sterility of life in our cities and suburbs, where most of our food is sold in gleaming supermarkets, packaged and polished, with no real transparency about where it may have come from, how it was grown, or how fresh it may be.” (Donnally, 2015).

Farmers Market at Willowsford Farms. Photo: Molly Peterson

The Willowsford agrihood development codified the well-being of the homeowners into the mission statement of their development: “[Willowsford will] integrate the farm into the fabric of the community; serve as a social and educational resource for the community; and encourage all members of the community to make healthy lifestyle choices, particularly in regard to the food we eat, our relationships with our home, and the activities we participate in.” (Willowsford, no date).

The specific reasons homeowners in agrihoods migrate to these developments may vary from person to person. As Ed McMahon with the Urban Land Institute observed, “People are gravitating toward communities that foster their interests.” (Donnally, 2015)

Challenges and Concerns of Agrihoods

Agrihoods built on abandoned commercial properties, like the Cannery near Davis, California, are often welcomed without concerns. And agrihoods built in land unsuitable for farming, including brownfields or previously contaminated areas, are also often preferred by urban planners. But agrihoods promoted as a way to conserve farmland by grouping subdivisions around working farms are not universally accepted by neighboring homeowners and farmers.

Agrihoods, like any new subdivision development, may bring a need for increased infrastructure, including roads, intersections, traffic lights, and sewer and water lines. A new 1,000-home agrihood may have major traffic implications for a rural area, if residents are working in jobs at a distance urban center that requires commuting. Incorporating mass transit planning and assessing ways to mitigate increased population should be an integral part of any agrihood planning.

Agrihood families value connecting to the land. Photo: Molly Peterson

Complaints about agrihoods also arise from those who feel that new farm-centered subdivisions are a form of “greenwashing,” where an insignificant amount of land is devoted to farming or conservation easements, with the vast majority of land slated for home construction. Some protests have been staged in county planning meetings against agrihoods, with concerns centered on the increased home density and traffic congestion that might occur. But well-designed agrihoods can consider these issues in the design phase.

While a traditional rural development often has only one home for every 10 or even 20 acres, an agrihood typically has a much denser housing component, which can keep a much larger portion of land in agriculture or green space than an unplanned subdivision might use. And new agricultural preservation policies at the city and county level are becoming increasingly common across the United States. These new zoning approaches can help direct developers to preserve open land and farm operations in agrihoods.

As more agrihoods are built across the country, the lessons learned in construction may lead to even more successful designs and environmental awareness. According to Ed McMahon with the Urban Land Institute, “The idea of bringing food into the heart of the development is going to be much more [accepted]. Today, it is sort of a novelty, but I think it is going to be far more commonplace in the future.” (Esposito, 2014)

Conclusion

Agrihood farmers markets help encourage healthy lifestyles. Photo: Molly Peterson

Agrihoods have spread rapidly in the past decade, and the number of new developments is accelerating. The combination of reduced developer costs and increased demand from prospective homeowners seeking a residential setting more in touch with nature has made this new agricultural subdivision design increasingly desirable.

Agrihoods can be especially beneficial to communities if they are developed on brownfields or other abandoned and disturbed lands, and can help communities suffering from insufficient housing if the agrihoods provide low- and moderate-income housing.

While the seemingly sudden appearance of agrihoods over the past decade across may seem to be just the latest development trend, it may in fact represent a revolutionary and permanent change in new home subdivision design. Daron Joffe, a farm-centered development consultant had this observation: “We should have farms integrated into our communities in perpetuity—that’s sustainability. That’s keeping people connected to place, to food, to land, and each other. It’s just a good idea.” (McColl, 2015)

Agrihoods

By Jeff Birkby, NCAT Smart Growth Specialist

Published June 2016

IP515

Slot 542

Version 100317

This publication is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development.