Hogs: Pastured or Forested Production

By Linda Coffey, NCAT Agriculture Specialist

Abstract

Hogs can be a good enterprise for some farms. Pigs do not require a lot of land, and their fertility and feed efficiency make them valuable meat sources. However, feed cost is a major issue, margins may be very slim, and raising hogs outdoors requires pasture rotation and fencing to protect natural resources. Weather impacts may harm production. Marketing will be a key to profitability, and this publication emphasizes direct marketing pork. It touches on factors to consider before beginning a pastured pork enterprise.

Pastured hogs, such as this one at Across the Creek Farm, off er a low-investment way to begin raising pork. Photo: Luke Freeman, NCAT

Introduction

Years ago, hogs were known as “Mortgage Lifters.” They were raised outdoors using home-grown and foraged feeds, and their productivity and efficiency made them useful on many farms. Today’s conventionally produced hogs are raised in confinement buildings to save land and labor and to simplify management. However, these buildings are expensive to build, maintain, and run. There are animal welfare concerns, as well. Margins are very slim, and diseases may be devastating in the crowded environment. Capital expense means large loans and a heavy debt load. Responsible manure storage and use is vital to avoid polluting soil and water. Odors may be offensive to neighbors, causing real estate and land values in the area to be impacted.

To escape the costly modern-day model, some producers are choosing to return to traditional ways of raising hogs: on pasture or in the woods. In contrast to the industrial model, hogs on pasture can be viable on a very small scale. The enterprise can then be expanded as the land base and market and labor allow. This publication describes the factors to consider and advocates using a “test batch” to assess feasibility before investing in the fencing and watering systems needed for a larger enterprise. As you read, consider the whole-farm situation to decide whether hogs on pasture or in the forest may work for you. This publication touches on several topics:

-

- Marketing

- Breed selection

- Processing—including finding, scheduling, yields

- Planning cash flow

- Protecting the environment

- Designing a pasture system: fencing, watering, and feeders

- Feeding

- Selecting and keeping healthy animals

- Handling

- Where to find more information

Jeremy Prater, Cedar Creek Farm, shows a group a self-feeder. Many thanks to Mr. Prater for sharing his experiences, which are featured in italicized quotes throughout this publication. Photo: Margo Hale, NCAT

It may appear to be putting “the cart before the horse,” so to speak, but knowing FIRST how you will sell your products will help you plan your enterprise, and that is why figuring out the marketing and processing comes first in our discussion. Breed selection is included between marketing and processing because it impacts both your story and how you will meet your customers’ needs.

After tackling marketing and processing, it’s hard to know what to address next. For this publication, we will focus on the whole farm and think about the infrastructure that will be needed. Feed costs are huge predictors of profitability and should be penciled out before attempting the enterprise. Assuming you choose to raise hogs, you will want to understand how to select and keep healthy animals.

Thinking through all these aspects and then working on a realistic budget before beginning the enterprise will either make you confident of your direction or turn you to another path.

Throughout this publication, the experiences of Jeremy Prater, hog farmer and direct marketer from Arkansas, are shared in italics. Of course, he is only one example. It is valuable to visit and talk with farmers in your own area to get the benefit of their local knowledge.

Marketing

“Marketing is the main thing. The best market is direct to the consumer. The hog market is RIDICULOUS. Factory farms have big contracts. The bigger world doesn’t need small-scale hogs, unless you sell it well, to someone who values quality. We cannot compete in the commodity market; we have to sell the STORY. If you’re not good at that, or don’t want to, don’t bother to raise hogs for sale.” —Jeremy Prater

As Prater notes, today’s conventional, large-scale hog market is not good for producers. The author recalls prices of 60 cents a pound (live weight) in the 1970s. In 1998, the author’s brother sold hogs for an unbelievable 8 cents a pound live weight, meaning a 250-pound finished hog was “worth” $20.00. At this writing, the price of hogs is almost back to 1970s levels. The price that farmers receive is not connected to the cost of production. However, your costs of production must be covered, and profit be added, for you to stay in business.

Having said that, this is not a hopeless case.

“Customers want pasture-raised hogs if they value ethically raised hogs that are out on pasture with high-quality feed. The pork is a different flavor from what is readily available. An easy sell is sausage, and if I was to recommend one meat item that would be it. We offered chorizo, Hmong, ground pork; get a great recipe. It stores easily and it is easy to cook.

Processing is the very first consideration, of course. Storage for inventory is another concern. Pork chops are hard to move: bacon is what everybody wants! You can choose to rent storage space, hoping a chef would want 300 chops at some point. Selling whole and half hogs helps a LOT. Another option is to do a CSA box delivery. That’s okay, but you are still sitting on a lot of inventory, selling 25 pounds once a month. Another option is to sell a larger poundage, quarterly. You could bundle with beef, too. Consider drive time, coordinating processing, and marketing time as costs that must be covered.”

—Jeremy Prater

Charlotte Smith of 3 Cow Marketing offers a lot of help in learning to market direct to consumers.

Effective marketing is the key to farm survival, and there are many resources to help you improve your skills in that area. For example, Charlotte Smith offers free trainings, including How to Create Your Own Website, Price Your Products for Profit, How to Create Facebook Ads That Sell, Get More Customers with Email Marketing, and more. She’s a farmer herself and is passionate about helping other farmers succeed. Her podcast is called Profitable Mindset, and she hosts a Facebook group called The Profitable Mindset. Charlotte offers short video trainings from her Facebook page. Here are some of her tips:

- You need loyal, consistent customers who will pay your price without question. You need to understand those customers and be able to meet their needs. Identify and then communicate with your “ideal customer” through website, social media, events on your farm, and in other ways. Marketing to “everyone” is marketing to “no one”; it’s important to gear your language and images to appeal to your specific ideal customer.

- You keep those customers when you:

a. Sell fantastic product that solves a problem for them

b. Give outstanding customer service

c. Connect with them on a consistent basis through emails that engage them in the farm story and communicate that you have what they need- To stay in business, you must charge enough to make a profit. We cannot compete based on commodity market price. Make peace with that, charge what you need to, and be able to say why your product is worth the price.

- Figure out what you are REALLY selling. For example, maybe your delicious pasture-raised pork will help them enjoy a festive holiday with their whole family or host a fabulous barbecue for their friends. Your blog can play up great recipes and include photos of a well-decorated table surrounded by happy people enjoying a special meal. Now you are not selling pork, you are selling hospitality, memories, and warm celebrations. Priceless!

As farmers, most of us have a lot to learn about marketing. Invest time and attention in learning the skills that will help your farm survive. Learn more at www.3cowmarketing.com/.

What are you REALLY selling?

As Charlotte Smith and Jeremy Prater have both pointed out, your customers for pasture-raised pork want something more than “meat.” Knowing what that is will guide your production practices and your marketing. For example, some customers will insist on non-GMO or organic feed. Others will be more interested in the animal welfare and environmental aspects. Some will simply want to support local agriculture. Raising hogs according to your own values is crucial, and then communicating why you do what you do, how you raise your animals, and what benefits there are for your customers is a key component of marketing.It can also help you find your customers. For example, Devona Bell (NCAT’s ATTRA Program Manager and a producer of pastured pork) states that she reached out to the “Holistic Moms” Facebook group:

“All of my pork customers wanted (in my case, organically fed) pasture-raised pork for health reasons (non-GMO or organic feed to avoid allergic reactions), for higher nutrient density, for animal welfare/environmental reasons, and to support environmentally friendly local farming. They valued knowing they were doing better for their health, their family’s health, and the environment.”

To keep your customer base, it is important to establish relationships and set your farm apart from cheaper, confined certified organic pork that is available in stores. They must see the value in supporting you and your business.

Should you decide that your niche will include organic production, see ATTRA’s Tipsheet: Organic Pig Production. To learn more about non-GMO production, various sections of ATTRA’s Non-GMO Dairy Transition Guide will be useful. Additionally, Food Animal Concerns Trust (FACT) has produced helpful handouts to use in explaining the nutritional benefits of pasture-raised meats. FACT reviewed a long list of scientific articles and presented some of the findings in engaging and brief information pieces available online at https://foodanimalconcernstrust.org/nutritional-benefits.

Why bother with non-GMO feed?

Non-GMO feed is more expensive than conventional. It is also harder to source. Many scientific studies have shown (in rats) that consuming GMO food is safe. So why should we consider paying more for non-GMO products?And why is this a consideration for hog feed?

First, a primer on GMOs, provided by NCAT Agriculture Specialist Lee Rinehart:“GMOs, or genetically modified organisms, are organisms that are genetically altered to possess specific traits, such as herbicide resistance or insecticidal properties to reduce crop yield loss due to weeds or insects. One such trait is Bt, in which Bacillus thuringiensis genes are transferred into the DNA of corn. The corn then expresses a protein that kills insects such as the European corn borer and the corn rootworm. Another trait, glyphosate resistance, imparts herbicide resistance into crops, such as corn or soybeans, to allow producers to use glyphosate to control weeds without harming the cash crop.

The principal feed grains for hog production include corn and soybeans, and both have been genetically modified for herbicide tolerance (HT) and/or insect control.

Seeds with the HT trait were planted on 93% of all U.S. soybean acres in 2013 and accounted for 85% of U.S. corn acreage in 2013. Bt corn, which is engineered to control the European corn borer, the corn rootworm, and the corn earworm, was planted on 76% of U.S. corn acres in 2013 (Fernandez-Cornejo et al., 2014).

Among the genetically modified feeds that include the Bt trait are corn silage, corn grain, and cotton (Bessin, 2004). The donor organism for this GM technology is the naturally occurring soil bacterium, Bacillus thuringiensis, and the gene used produces a protein that kills corn borers and rootworms in corn, and the bollworm and tobacco budworm in cotton. Bt corn and Bt cotton are used by producers to reduce or eliminate the application of insecticides.

Crops that are resistant to glyphosate (i.e., Roundup™) include corn, soybeans, alfalfa, and cotton, and these represent the vast majority of GM crops worldwide (Duke and Powles, 2009). Producers adopted these HT crops primarily due to perceived cost savings and easier weed management (Fernandez-Cornejo et al., 2014). However, with the rise of herbicide-resistant weeds, farmers are opting for higher herbicide applications or are switching to alternative herbicides and/or sustainable weed control methods.

Sourcing non-GMO grains can be an issue, depending on your location. Most feed grains in this country are produced using genetically modified seed, and not many mills adequately deal with non-GMO products, due to limited demand, lack of infrastructure for storage and transportation, and the cost of providing traceability services for the producer.”

You may learn more by finding one of Howard Vlieger’s presentations on YouTube.

An Iowa hog farmer and activist, Howard Vlieger, participated in a scientific study looking at the effects of feeding GMO or non-GMO feed to hogs. This study found that pigs fed a GMO diet had a higher rate of stomach inflammation and heavier uteri than pigs fed a comparable diet using non-GMO ingredients. The researchers cautioned that pigs have a similar gastrointestinal tract to humans, and therefore believe it would be “prudent to determine if the findings of this study are applicable to humans” (Carman et al., 2013). Mr. Vlieger has traveled the country speaking about the risks from GMO foods and glyphosate residue.

One example of hog farmers meeting customer demands for non-GMO feeds is that of Jeremiah Jones and the North Carolina Natural Hog Growers Association, which he began and presides over. The farmers in the cooperative grow their own feed, and the cooperative owns a processing plant that roasts and presses the non-GMO soybeans and grinds the meal. Because of pollen drift, there is a lot of testing required to be sure that feeds are indeed non-GMO. This is expensive and must be figured into the cost of doing business. Jones pointed out the necessity of feed that is properly balanced for the needs of the hogs, and the cooperative consults a nutritionist to achieve this balance (Jones, 2020). You can learn more about the cooperative by watching the short video, Learning About Our Pork Supply: The NC Natural Hog Growers Association.

When considering possible venues for marketing your pork, remember the wisdom of not being solely dependent on any one customer. Chefs come and go; grocery stores may suddenly decide to stop giving shelf space to your product; an institutional buyer may move on. However, while having some diversity in marketing is smart, spreading yourself too thin by trying to “do it all” is a recipe for burnout.

Farmers markets are a way to grow your customer base. Photo: Robyn Metzger, NCAT

To reiterate: you need to be ready and able to tell your story and convince customers that YOUR product will solve their problem or need.

Shannon Hayes, producer and direct-marketer of meat at Sapbush Hollow in New York, wrote on this topic:

We’ve found that it is the intangibles that sell our products. By meeting our customers’ deeper needs, we can capture and hold on to these people as loyal buyers. What are those needs, and how do we develop such loyalty?…..we have found that their needs surround issues of security, ideals, and community….Large agricultural corporations are already working to mimic the healthful benefits of grassfed products, but they cannot meet the direct marketer’s competitive edge when it comes to security. Our customers know the source of their food and how it was raised….We embody a set of greater ideals for our customers: the survival and revival of the family farm, the economic security of rural America, responsible environmental stewardship, protection of open spaces…We are a face, a voice, a handshake, and, as customers return, a friend. (Hayes, 2002)

See the resources listed at the end of this publication to learn more about direct marketing meat.

Dave Scott of Montana Highland Lamb is an NCAT Livestock Specialist and has written an engaging and informative publication that covers topics relevant to direct-marketing meat. Direct Marketing Lamb: A Pathway is available on the ATTRA website and includes discussion about producing a quality product, finding a processor, minimizing pre-slaughter stress, understanding the cutting process, fulfilling the customer’s need, promoting your product, labeling, pricing, moving inventory, and identifying market venues. Here are some of Dave’s lessons about market venues, which apply to pork as well as lamb.

- The consumer drives your marketing. If you lose touch with consumer preferences, your business will sputter.

- Invite your customer to your farm to build relationships and customer loyalty.

- Farmers markets are great for gathering customer feedback and for charging full retail price, getting the word out there about your farm, and meeting customers in person. However, they take a lot of time and energy.

- Restaurants can be great for having a steady and relatively high-volume demand for your product. You must build relationships with chefs in order to sell to restaurants.

- Institutions may be great places to market your meat. Consider hospitals, senior-living facilities, local universities and schools, and even national parks.

- Retail stores and meat CSAs are other possibilities. You will need to have a consistent supply of meat with a local flavor.

- The quality of the product itself is the most important factor, and it must fulfill a customer need, even if that need has to be inspired through education.

- Serve your present customer base well before expanding. (Scott, 2016)

Learn more about marketing meat by listening to ATTRA’s podcast, Voices from the Field, which features Dave and Jenny Scott of Montana Highland Lamb in several episodes on that topic. The first two segments aired on November 20, 2019, and December 4, 2019. Subscribe to Voices from the Field or listen from the ATTRA website.

Breeds

The breed you raise will help determine your product’s characteristics and your “story.” There are many breeds that will work as pastured hogs. Your choice will depend on the following:

-

- Availability

- Cost

- Customer preferences (is it important to raise a heritage breed?)

- Your own preferences

“Picking a breed is like buying a car. They all have their good features and their drawbacks. Interview several producers. Ask a lot of people. The gene pool is limited in heritage hogs, and they get inbred very quickly…Heritage hogs grow slower, so from birth to finish would take nine months to a year.”

—Jeremy Prater

Some breeds do not fit into industrial models and are susceptible to population decline. They are dependent on outdoor producers to continue raising them to keep the genetics available.

Many breeds will work on pasture. Figure out what your customer wants and then choose your breed. Crossbred hogs are perfectly acceptable for meat production and can often be hardier than purebred stock. Photo: Margo Hale, NCAT |

This young Hereford pig is an excellent choice for farmers who want to raise a heritage breed. Photo: NCAT |

This Hampshire hog also works well on pasture, and may offer better growth and muscling than some heritage breeds. Again, know what your customer wants! Photo: NCAT |

These traditional breeds were bred to be good foragers, good mothers, hardy, long-lived, and adaptable. This can be advantageous for production and can also be a marketing point. The Livestock Conservancy has gathered materials to help inform producers how to market heritage pork and offers information on health, marketing and budgeting, carcass characteristics of heritage hogs, husbandry, and history, as well as a chart comparing heritage breeds of pigs. The chart lists nine breeds of heritage pigs and provides photos, adult weights, ideal harvest weights, expected litter size, and information about temperament, mothering, foraging ability, and other notes of importance.

Again, understanding what your customer wants is key. If customers are interested in pasture-raised, lean hogs with large loins, a heritage breed is not necessary and could work against you: they tend to put on more fat and have lighter muscling. On the other hand, some chefs might happily promote heritage hogs on their menus as a selling point, and they may insist on pigs that have more fat to result in juicier pork. You might want to run two small test batches and offer some samples of both heritage breeds and more modern breeds to your customers (and to your own family). When you really are enthusiastic about your product, you will attract more customers, so be sure you eat your own products and can speak honestly and convincingly about what makes your pork special.

What breed do you want?

Producers will have to weigh the features that are most important. This is subjective and individual: that is why there are so many breeds with varying characteristics. Following are some factors to examine:

- Size of mature animals (impacts feed needed and weight of market animal)

- Feed efficiency (how much feed does it take to put on a pound of gain?)

- Growth rate (how long does it take to get an animal to market readiness?)

- Litter size (some breeds are known for larger litters, which means more pigs to cover maintenance cost of a sow)

- Mothering and milking ability

- Carcass characteristics (leanness, muscling, yield, meat quality, and taste)

- Local availability

- Hardiness

- Temperament

- Foraging ability

- Color (white breeds tend to sunburn)

- Personal preference

- Breed name and history (Can you boost interest in your meat by having a unique breed with an interesting story?)

As stated by Jeremy Prater, no one breed will offer ALL of the desired traits. And your priorities may be different from your neighbor’s, so you may each choose a very different breed.

Breed Characteristics

Many breeds will work for outdoor production, and many breeds will provide excellent meat quality. Consider the traits that are important for your system and for your customers, and select high-quality, healthy pigs from breeders who are raising their hogs the way you want to. Crossbred hogs can work very well; there is no requirement for purebred stock if you are selling meat. If you intend to also sell breeding stock, however, you may want to begin with high-quality purebred stock. Health is paramount! Starting with healthy animals will be more important to your success than will choosing the “right” breed. See the “Health” section later in this publication for more on how to select healthy animals.

Processing

Of course, you have no meat to sell without a processor. If you plan to sell whole or half hogs directly to individuals in-state, a custom or state-inspected processor will be fine. However, if you will be selling cuts or selling to restaurants or stores or across state lines, then you must use a USDA-inspected facility. It’s a good idea to ask around your area to learn about the experiences of others regarding working with a processor. You can learn a lot that is relevant by reading these related ATTRA publications:

Direct Marketing Lamb: A Pathway

Working with Your Meat Processor

Be sure that you understand what your customers want. What size chop? How much fat? What thickness of bacon, and what kind of cure? Be sure to communicate all of this clearly to your processor. Additionally, if you are feeding a non-GMO or organic feed, you need to request that your pigs be processed first on the sanitized equipment, prior to conventionally raised pigs being processed. Work with the processor to receive back all of your pig, including the organ meat, bones, and fat. You want to ensure you receive back your own pig parts, and not organs that have been put into a drum and mixed with other products that are fed conventionally and possibly confined. If you are marketing certified organic meat, you must not only have your farm certified, but you must also use a processor that has organic certification. If you cannot find a certified processor, or if you are feeding organic feed but are not certified organic, talk to the processor about using cleaning products that comply with the organic standards, maintaining traceability, and keeping your carcasses separated from conventional hogs.

The bottom line is that you must work respectfully with your processor to get your customers exactly the product they want.

Some guidelines will help you build a good working relationship

with a meat processor:

- Understand the processor’s needs

a. Scheduling in advance

b. Clear communication

c. Prompt payment and pickup of product

d. Repeat business

e. Steady and manageable stream of work- Understand your role in producing excellent product

a. Managing for proper finishing of livestock

b. Handling livestock calmly

c. Providing clear instructions for aging and cutting (and curing) in a timely manner- Have realistic expectations

a. How much meat will this animal yield?

b. How far in advance should I call to schedule? Be aware of seasonality issues.

c. How much should I expect to pay for services?

Address all concerns quickly and respectfullySource: Working with Your Meat Processor (Coffey, 2017)

Scheduling

Processing at the right time is important for your meat quality and for profitability. For example, if you send a hog to the processor before it is “finished,” there will be insufficient fat for good flavor and not as many pounds of pork to sell. On the other hand, holding a hog well past the point of finish means that your hog will have excess fat, which may need to be trimmed and may send a negative impression to your customer and cause the animal to yield less meat than expected. Also, it will have consumed a lot more feed, which drives up the cost of production. Feed efficiency decreases as the hog gets heavier because the animal uses more feed just to maintain weight, compared to lighter animals.

However, most processors will be booked well in advance. This means that you must be able to predict a “finish date” and schedule the processing appointment ahead of time. This can be tricky until you get experience. A hot summer may mean your hogs don’t eat much, and therefore do not grow as fast as you projected. Some breeds finish faster; if you are raising a breed for the first time, it may be especially difficult to predict. Also, if your animal will be ready during deer season, or right after the county fair, when many other animals may be sent to the processor, it’s especially important to book early.

If you find that your hogs are ready before their appointment date, you may:

-

- Restrict feed by hand-feeding rather than using a self-feeder

- Ask the processor to let you know if he has a cancellation and can accommodate you sooner

- Ask another customer if they can trade slots

- Make a note to call sooner next time

If the pork will make a negative impression on your meat customer due to improper finishing, you can choose to consume it yourself or have it processed into a product (such as sausage or brats) where the finish is not readily apparent.

Predicting Finish Time

Because of all the factors that influence growth rate, each group of hogs will be different. Your “test batch” will give you the best information on how and when your hogs will finish. Here are two examples of finish times:

-

- Researchers in Iowa tested Berkshire pigs on full feed in hoop houses, running batches in the winter and in the summer to get an average of weather conditions. On those particular groups of pigs, raised from 56 pounds average initial weight to 271 average weight at slaughter, it took 122 days on feed, with just under 6 pounds of feed consumed per day, and an average daily gain of 1.77 pounds. For this group of pigs, feed-to-gain ratio was 3.3:1 (Linden, 2014).

- NC Choices provided a look at pastured pork budgeting, and its hypothetical illustration estimated starting weight of 50 pounds and finish of 250 pounds, taking six months on pasture. Putting on the 200 pounds of gain requires 700 pounds of feed (NC Choices, 2016).

Notice the variation. To fully understand your own costs and timing, you will need to keep good records. More on this later.

It’s a great idea to keep records about finish time so that your scheduling improves in the future.

Factors Influencing Hog Growth Rate

- Genetics—heritage breeds generally grow more slowly

- Weather—hogs eat less in hot weather, and use more energy staying warm in cold weather

- Feed quality—balanced nutrition for the age of the hog, palatable, fresh

- Feed quantity—provided free choice for the best growth

- Health

Yields

Hogs in the forest will still need feed. This self-feeder is the most convenient way to provide free-choice feed, which results in the best growth rate. Photo: NCAT

As mentioned above, finishing (level of fatness of the animal) will impact meat yields. So do breed, size of the animal, and cutting instructions. A common problem processors report is that producers believe they did not get all their meat back after processing. Often, that is because producers do not understand the losses due to transport and slaughter and then cutting and wrapping. For example, the hypothetical 250-pound hog from the NC Choices Pastured Pork: Breaking Down the Cost illustration will yield a 180-pound carcass, which will result in 123 pounds of cut and wrapped meat available for sale. Requesting more boneless cuts will reduce the pounds of pork received. For rough figuring, you can estimate the carcass will be about 70% of the liveweight. For boneless cuts, 65 to 70% of the carcass weight will be returned as meat (Raines, no date).

Again, breed and cutting instructions impact yields. There was an interesting study done by the University of Kentucky in which eight different heritage breeds were raised to finish weight and then processed and the primal cuts weighed. This gives great information, if you are raising one of those breeds, so you know how many pounds of each cut you are likely to get. This helps in figuring out pricing and in projecting pounds of salable meat.

Primal cuts are meat portions initially separated from the carcass during processing. The primal cuts for pork are as follows:

- Shoulder

- Leg

- Loin

- Belly

As stated previously, only your own test batches will be completely relevant. However, if you are planning to sell cuts and are sorting through several breeds, this study may aid your decision. Some of the data are presented below. Notice the variation in carcass weight, backfat measured at the first rib, loin eye area in square inches, and salable yield of the carcass when cut in the American style. In the article, there is much more specific yield information.

Considering the Enterprise

Once you have figured out what your prospective customers want, found a processor to work with, and developed your marketing plan, it’s time to assess the feasibility of the enterprise. There is no point in going through all the work unless it can be profitable. But you cannot assess feasibility unless you begin with realistic parameters.

“Looking at pasture or woodland management, be cautious when beginning to raise hogs this way. Realize that farrowing is one business and raising pigs to finish is another. As you scale up, management gets complicated. I recommend that beginners choose to focus on one or the other. It’s cheaper to buy piglets and raise to finish.” —Jeremy Prater

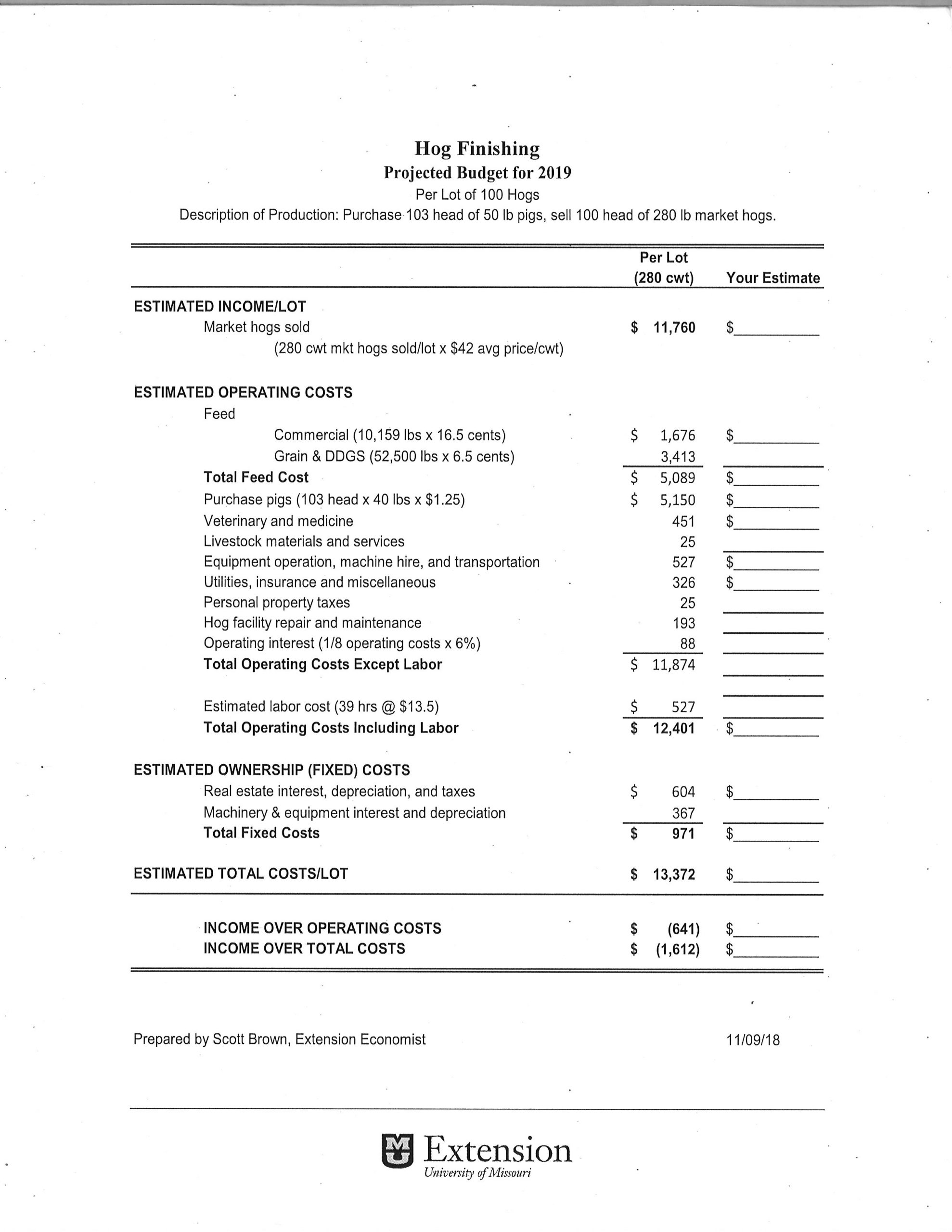

Budget for finishing hogs. Source: University of MO

Not only does management get more complicated as you scale up, as noted by Jeremy Prater, but also the money needed up-front becomes a substantial barrier. Consider the funds needed to purchase:

-

- Livestock

- Feed

- Processing service

- Trucking

- Hog-handling facilities (such as a pen and chute)

- Fence (to expand area allotted to hogs)

- Equipment for production and marketing

- Freezer space to store inventory

- Marketing

- Veterinary care

Most of these costs multiply with the number of hogs raised, and these costs must be paid before the animals are sold. So, to begin, start small. Also, if your business is to sell pork, it will be cheaper to begin by buying just a few pigs to raise to finish. This “test batch” will provide vital information about feed costs, growth rates, meat yields, and meat characteristics. Then, if this test proves profitable, you can scale up as your market and cash flow will allow.

“How much feed in a hog? For us, to reach a target finished weight of 300 pounds would take 900 pounds of feed with a good pasture rotation. So, you can look at the price of feed and see what you’d need to get for the hogs.” — Jeremy Prater

Of course, there is more in the pork than just feed. And the source of feed will greatly impact the cost, as well. See the Feeding section for more about that. For a look at possible costs for all types of operations, including farrowing, see Missouri’s budgets for various kinds of livestock enterprises .

Note that the Missouri budgets assume conventional management and marketing. Your direct-marketed pork will have a different price, set by you after considering all your costs. Reading this publication all the way to the end will help as you figure out what costs you must consider for your own enterprise.

The Whole Farm

As stated earlier, marketing and processing are key to the success of a pastured or forested hog operation. However, the production aspects are also vital. Those will be briefly touched on below. Before we discuss production of the hogs, however, it is important to consider the whole-farm environment and how to use hogs to enhance—and not harm—the land.

Protecting the Environment

Raising hogs outdoors on pasture or in the forest can be a very beneficial practice for the hogs and the land…or it can be a disaster. You, the steward of the land and animals, will determine which it is by your attention to both. For good animal welfare, we want to “let hogs be hogs”—but recognize that too many hogs in one place for too long will degrade and pollute the area:

-

-

- by removing too much vegetation, resulting in soil erosion, compaction, and runoff, lowering soil organic matter, and reducing water-holding capacity

- by hooves causing compaction, and by wallowing and rooting

- by depositing manure and urine in quantities too great for the soil to absorb, especially in areas with little vegetation

-

These hogs have focused their rooting on one area of the pastured pen, but if hogs remain in the area long enough, they will remove more vegetation and will compact the soil. This pen will be rested for at least six months after this group of pigs is harvested. Notice the off set hot wire inside the pen that prevents wear and tear on the fence. Photo: NCAT |

In the summertime, hogs rely on wallows and shades to keep their body temperatures regulated. Photo: NCAT |

Hogs love to root to find grubs, worms, and roots. Photo: NCAT |

A portable waterer can be moved to a new location to prevent a messy mud hole at the watering point. Photo: Margo Hale, NCAT |

These actions will damage the life under the soil surface and on top, and the hogs themselves may suffer internal parasite infections, pneumonia from inhaling dust, and joint problems from walking on compacted surfaces. This is not what anyone wants on his or her farm.

Notice the bedding provided for these hogs. They have removed the vegetation in their pen and created a wallow near the fence, and this bedding will give the hogs a way to stay warm while also providing some protection for the soil. This pen will need rest and perhaps replanting when the hogs are moved. Photo: NCAT

Be wise in planning and implementing a hog production enterprise, respecting the farm itself first of all. Here are 10 areas identified by the Center for Environmental Farming Systems that will help in setting up a farm for fewer negative impacts from pastured hogs.

-

- Drinking water management—can you move locations, or have multiple locations? Protect the soil under the waterer with a pad or slats?

- Ground cover management—it’s imperative to keep vegetation growing and alive to protect soil and water. Rotate!

- Wallow management—Can you provide shade and shelter to minimize the need for wallows? Be sure there is thick buffer vegetation around wallows.

- Length of time hogs occupy a space before a break—impacts vegetation cover, nutrient loading, and compaction

- Length of rest before putting hogs back on the land—let the vegetation recover

- Field renovation—it may be necessary to smooth a field and perhaps plant a crop after hogs have used the land

- Nutrient management—hogs pass more than 85% of the nutrients they consume back onto the land. Test and then, if needed, remove a crop to prevent the land from being overloaded with nutrients

- Buffer considerations—thick, healthy vegetation buffers (wide strips surrounding a field) will trap sediment and nutrients, protecting waterways from nutrient runoff

- Trees and woodlots—keep trees healthy by not allowing hogs to be in the area for too long

- Stocking rate on the farm—ground cover can only be preserved if stocking rate is appropriate. In this temperate environment (in North Carolina), 15 to 30 growing hogs per acre worked under continuous grazing, provided that a sufficient recovery period was given after no more than two cycles of finishing hogs

To sum up in one word: ROTATION. Rotating hogs to different pastures and allowing adequate time for forage regrowth prevents hogs from damaging vegetation (including trees) and therefore will protect the soil. Taking soil tests every other year will help in understanding how nutrients are accumulating where hogs have been raised. Vegetated buffer strips can help prevent those nutrients from moving into waterways. Ideally, hogs will be part of a rotation that grows a crop following the hogs, to use the fertility the hogs left behind and keep it a resource and not a problem (Pietrosemoli et al., 2012).

Consider the terrain and how you will ensure that areas are not stripped of vegetation. No amount of rest will replace topsoil that has washed away. In addition to the practical steps listed above, the way you fence a pasture can mitigate or increase a problem. Fencing along the contour helps prevent erosion because the hogs will naturally root along the fenceline, creating a berm that will help hold soil and water (Pietrosemoli et al., 2012). During wet times, or when you are concerned about the ground cover for any reason, it will be useful to have a bedded sacrifice area to contain hogs for a short time, until the ground is not saturated and the vegetation can recover. Preventing excessive impact is key.

For the long-term health of the farm, respecting the tenets of soil health is vital. As a reminder:

- Green growing plants for most of the year

- Cover the soil

- Diversity of plants

- Do not disturb

Hog manure can be a treasure for your farm, increasing fertility and soil health. Just remember that too much of a good thing is a BAD thing. When soil tests indicate that nutrients are becoming excessive, there are some things you can do to remove the excess:

-

- Grow a hay crop or vegetables or grains

- Flash graze: put sheep or cattle on the field for a short time and then remove them

- Move feeders and waterers to a new location, when possible, to avoid a heavy accumulation of manure in those areas

For much more information about protecting the environment while raising hogs outdoors, refer to Conservation Practices in Outdoor Hog Production Systems: Findings and Recommendations from the Center for Environmental Farming Systems. This publication is 38 pages long and includes many photos, diagrams, and charts that illustrate concepts and research results. Case studies from six on-farm demonstrations are included, and many practical suggestions are provided, based on the years of research done in North Carolina. Find this publication and many others concerning outdoor hog production at: https://cefs.ncsu.edu/portfolio_tags/outdoor-hog-production/.

Designing a Pasture System: Fencing, Watering, and Feeders

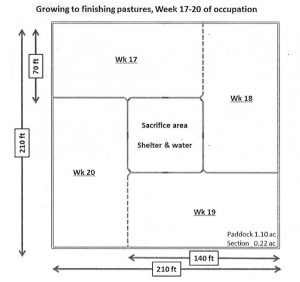

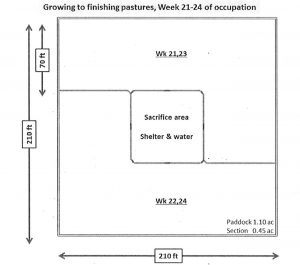

This section discusses the infrastructure needed to raise hogs on pasture, always keeping in mind that protecting the environment and providing for the animals need to happen at the same time. To begin, it may be helpful to look at the system used in North Carolina at the Center for Environmental Farming Systems. This setup uses exterior fences of either woven wire or four-wire electric fences, and internal fences of one or two strands of aluminum wire or polywire. Shelter and water are in a central location, which is a sacrifice area or heavy use area (HUA). Surrounding the water and shelter area are eight pastures constructed with temporary fencing. This allows flexibility in pasture size. Feeders are placed in the pasture with the hogs and moved each week as the hogs rotate to fresh pasture. See Figure 1. As the animals grow, some division fences are removed to accommodate the space needs of the larger animals.

This can be a labor-saving way to raise hogs. How to provide the water and how to move and fill feeders are major considerations. Your farm may be better with a different setup. Think through the logistics of animal movement, feed and water delivery, future uses of the pasture, and how to provide shade in your own situation. Remember, too, what it will be like to drive on that land to deliver feed after a heavy rain.

Growing to Finishing Pastures, Week 1 to 26 of Occupation

These pasture systems could accommodate 20 growing hogs in North Carolina’s temperate environment. Note the dimensions given to gain some idea of the space you would need to allot for your animals. This is only a guideline; your weather, topography, vegetation, and soil type, as well as the size and rooting behaviors of hogs, will all affect the appropriate stocking density on your own farm (Pietrosemoli and Green, 2015).

Figure 1 After week 16, pigs will have access to two sections in a weekly basis. Dashed fence lines will be removed after week 20.

After week 20, pigs will have access to 0.45 acre in a weekly basis. This section will be used twice.

Fencing

Because of the need for rotating hogs to protect the land, electric fencing is often the best option, as it is portable and flexible. Hogs must be trained to electric fence. For electric fencing to be effective, here are important considerations:

-

- Have a good charger—and a backup in case of malfunction or lightning. See Electric Fencing for Serious Graziers for details about installing and using a good electric fence. An electric fencing company will also have recommendations and equipment. According to the fencing company Zareba: “To safely contain pigs, you need a fence charger that maintains a minimum of 2,000 volts on the fence line.”

- Train young pigs to electric fence before putting them in the pasture or forest.

a. Put animals inside a secure pen.

b. Run electric wire inside the pen at nose level of the pigs; you may attach something attractive to the wire so the curious pigs will touch the wire and receive a shock.

c. Be sure all the pigs have indeed experienced the shock from the wire before removing them from the pen. This may take a week or so. - Pay attention to the spacing of the wires. Start no more than six inches from the ground with the lowest wire, then move up depending on the size of the hogs to be contained. According to Zareba: “We recommend a minimum of three strands of wire for pigs and a fence height of at least 24 inches.” Use offset electric wires inside any permanent non-electric fence so that hogs will not dig under fences. This wire should be about six inches or less from the ground.

- Inspect the fence regularly and correct any problems. Look especially to be sure the hogs have not pushed dirt over the lower wires, as this will short out the fence.

For a small group of hogs, you may be able to use permanent fence. For example, a shady pen constructed with woven wire or with hog panels and T-posts can be easily built and, if it is lightly stocked, it may serve well for six months to grow out a few pigs. Pay attention to gates and be sure hogs cannot get their noses underneath and take them off the hinges. Hogs are strong and will try to bulldoze under a gate or fence to escape to greener pastures. Barbed wire is not a good idea for hogs, but a single strand stretched tightly at the bottom of a woven-wire fence will discourage hogs from digging. Hog fences need to be tight and well-braced.

To divide pastures, a single strand of hot wire may work. Electrified hog netting can work well, also, but takes a lot more charging. Check the website of a fencing company, such as Zareba or Premier 1 or StayTuff, to investigate options. [Note: Product names are mentioned for illustration purposes only, and this does not constitute an endorsement of a particular product by NCAT, ATTRA, or USDA.]

This solar charger is effective in powering the electric fence that keeps the hogs in their pen. The hogs have rooted extensively along the edge at the fenceline, though there is vegetation elsewhere. Photo: NCAT |

A hog pen can be constructed using permanent fence, such as this one that features hot wire on one length. Photo: NCAT |

Step-in posts and polywire make an effective temporary fence. Pay attention to the height of the strands and keep the fence charged with at least 2,000 volts. Train pigs to electric fence before putting them in the pasture. Photo: Margo Hale, NCAT |

Watering

Watering is critical and may be hard to figure out. Consider how you will provide clean water that the hogs cannot lie in. Natural water sources need to be protected from hogs; you may be able to pipe water from a spring or a creek, but the animals should not be allowed access to the source itself. One way to provide water and yet rotate the pastures is to place the water in a central location, with a concrete pad or heavy use area, and let all the pastures feed into that location. Feeders can be placed in the pasture with the hogs, which helps with manure distribution throughout the pasture. An example of this system is illustrated in Designing Pasture Subdivisions for Practical Management of Hogs, from the Alternative Swine Research and Extension Project. See Figure 1.

For small numbers of pigs, a water barrel can be fitted with nipples so that several pigs can drink at once. Nipples are clean, and pigs quickly learn to use them. Smearing a little jam on the nipples when introducing to the pigs will help the pigs figure it out quickly. Small farms can be creative in supplying water, as in the top left photo below from The Farm at Barefoot Bend, owned by Damon and Jana Helton. Notice the nipple extends into the pen. The container is filled at a hydrant and then moved out to the pasture with a tractor.

Other designs allow hogs to drink more water at a time, but these need to be cleaned frequently. See the barrel fitted with a bowl valve (bottom left) and the metal water tank with drinking area (top right). In both cases, the hogs transfer mud to the drinking water, and it settles in the bottom and must be cleaned out.

This watering solution features a nipple fitting on a large container. Photo: NCAT |

This tank offers the advantage of hogs consuming more water more easily. However, it must be cleaned out frequently. Photo: NCAT |

Bowl-type fixtures need frequent cleaning. Hogs press the plate to release more water. A pad of some sort underneath this fixture would be helpful. Photo: NCAT |

This Hereford hog is enjoying the water trough! When offered open troughs, hogs will choose to lay in them and also flip them over, making a mess in the pasture and leaving themselves with no water until the farmer notices and refills the tank. Photo: Daniel Beal, Blackberry Hill Farm |

Hogs are strong and playful; keep the water barrel full, and if possible, put it on a pad outside the hog pen to prevent them knocking it over. Never let them run out of water; it is critical for their health.

Commercial frost-free waterers are essential in cold climates. The disadvantage of these waterers is that they are permanent. Wherever they are placed will become a heavy-use area and will need to be prepared with a pad of some sort so that hogs don’t produce a wallow. Perforated platforms or slats under feeders and waterers can help protect heavy-use areas, and you can also put down biodegradable materials such as hay, straw, leaves, or wood chips to protect areas that get a lot of traffic. Remember to keep the soil covered.

Home-built watering systems can be found by searching YouTube; many innovative and inexpensive systems have been built by other farmers.

Niche Pork Production Manual

As you research the feasibility of this enterprise, the 2007 publication Niche Pork Production Manual will be a useful source of practical information on many aspects of raising hogs. Of course, costs will need to be updated using current numbers, but this comprehensive collection of concise articles will be a great help in learning about hog production. There are nine sections within this manual: Records, Environment, Nutrition, Reproduction and Genetics, Production Flow, Pork Quality, Pig Husbandry, Managing Feed Costs, and Managing Non-feed Costs.

Feeding

These pastured hogs are old enough to enjoy some grazing but also need a constant supply of free-choice feed, such as from this self-feeder. Check the feeder daily to ensure that feed is flowing well but not being excessively wasted. Photo: NCAT

“We’re talking about pastured hogs, but we have to realize, they are not forage-finished. When I was figuring out what to do, I went back to the past: 1920s and 1930s, when they were raising hogs on pasture, before the industrial model became the norm. I found an old technical manual, which gave good baseline numbers for sows on forage: one acre per sow, intensively. You have to have grain unless you do succession planting…The source of feed is very important. We used Hiland Naturals (GMO-free) feed, in bulk. For raising just a couple of pigs, of course you could just buy sack feed from the local cooperative. It is more expensive than bulk, but convenient. People think they can just feed a hog whatever, but the fat and protein levels need to be right. Buy a balanced feed. You can’t starve a profit! Pigs are not ruminants. If you are going to mix your own feed, consult a nutritionist so you don’t mess up.

Raising hogs on a large scale requires feed bins to allow purchase of bulk feed to save cost and provide for adequate storage of large quantities of feed. Where will you source the feed? Finding a good feed mill and a quality feed is critical for success. Photo: NCAT

Another concern is how are you going to deliver feed to the hogs? One way is to haul in a 55-gallon barrel to a heavy-use area and feed in troughs. As they grow larger (or as your herd does), a gravity-fed feeder is great. We would use 1,000 pounds every few days. The nice thing about hogs is they can use a self-feeder, having feed available all the time. They don’t overeat.

But if you have sows also, they need a different ration: lower in protein, with a different mineral formulation. And they should be fed by hand because they will get gigantic! They have birthing problems if they get too big…”

START SMALL. It’s easy to scale past your competency, past cash flow, past your market.

Consider that it will probably cost around $300 for feed for EACH PIG, and that you must pay that bill before YOU get paid. The margin is rarely better than $100 per hog before labor.” —Jeremy Prater (Author’s note: The manual Jeremy refers to is listed in the Resources, author William W. Smith, 1920.)

As Prater pointed out, hogs are not ruminants. You must provide a good, balanced feed for optimal health and performance and allow the pasture and woodland to provide supplementary nutrition. The Niche Pork Production Manual includes sections on feed budgets, nutrition, and managing feed costs. All of these topics are important for success. In “Reducing the Cost of Pig Diets,” the authors note that actual data from nine niche hog operations showed a 4:1 feed conversion ratio: that is, it took four pounds of feed to get one pound of gain (Lammers et al., 2007). Although this may give a starting point for figuring how much feed you will need, feeding your own pigs in your own management system will give you much better information.

As hogs get older and heavier, feed conversion drops (it takes more feed to get a pound of gain). As shown in the table on page 17, young pigs need more protein. If older pigs are fed protein at this level, it is a wasteful expense. Adapting the ration to the stage of growth will save money and result in better gains.

For raising a few pigs (the test batch), it will work to buy 50-pound bags of feed from your local cooperative. It will be more expensive, but also fresher. Once you get past the test batch, though, feed becomes much more of an issue.

“We would use 1,000 pounds every few days. The source of feed is very important. And be sure to consider the amount of money you need upfront to purchase all the feed. How will you move feed around the farm? Do you have a tractor that will be capable? Size your herd to the equipment. Consider that it will probably cost around $300 for feed for EACH PIG, that you must pay that bill before YOU get paid. We bought non-GMO feed, in bulk. We have a feed bin: that’s another expense, but necessary if you are raising a lot of stock.” —Jeremy Prater

For young pigs (under 100 pounds), don’t plan on the forage providing much nutrition. The pigs cannot digest it well. As they adapt to forage, they will begin to eat more of the pasture. They must be rotated to protect the pasture and to reduce internal parasite infestation. For the best meat quality, pigs need full feed (all they can eat); they will grow faster and the meat will be more tender. Don’t restrict feed for growing hogs. Self-feeders work well because hogs will not overeat. Allow a self-feeder space for every three to five hogs (Klober, 1997), so that all pigs will get their share.

Feed Cost Impacts Break-Even Price

This “Pastured Pork: Breaking Down the Cost” illustration from NC Choices shows how feed source and cost will impact the price a farmer must charge for meat. Here are the figures for the hypothetical hog.Assumptions: All pigs cost $75 at 50 pounds, need $35 labor, $56 in other farm costs, $44 transportation, $200 for processing (fresh meat only), and $65 for marketing and sales. They will put on 200 pounds during six months on pasture (from 50 to 250 pounds) and will yield 123 pounds of meat for sale.

What about lowering feed costs by feeding garden produce or other foods? Hogs have historically been great recyclers of all kinds of feedstuffs. However, many states have regulations that forbid feeding “garbage,” such as restaurant waste or grocery store-rejected produce. Foodstuffs containing meat may not be fed to hogs, and in some states, produce is considered “garbage” and must be cooked before feeding to hogs. Milk and whey help hogs to gain and provide extra protein, but hogs will still need other feed in order to grow well and be healthy. Some producers use spent brewer’s grains or other feedstuffs. If you have access to materials such as brewer’s grains, that can help cut cost. It can be a hassle to pick up and feed, and it must be either used quickly or ensiled to preserve it so that it doesn’t mold. Moldy feed is harmful to livestock, including hogs.

During the fall, especially, older pigs will enjoy foraging for nuts and fruits in the forest. Be sure to rotate so that the land is not degraded and give the area adequate rest before returning. Photo: NCAT

If you have forest that includes mast trees (that is, trees producing fruit, nuts, or seeds), allowing hogs to forage in the fall can be great for their health and help put on weight very cheaply. Mast trees include oaks, hickories, walnuts, buckeyes, chestnuts, hazelnuts, hawthorns, beeches, crabapples, persimmons, and more. Commercial fruit and nut orchards may serve as sources of food for your hogs as well, where they can eat fallen nuts and fruits to get rid of pests (Thistlethwaite, 2015). “Hogging down” a crop field after combining, or instead of conventional harvest, can be a great way to supplement hogs and add fertility to a field.

For all these options, it is very important to manage the stock in a way that doesn’t degrade the environment. Refer to the previous section “Protecting the Environment” before starting, and then be sure to watch what is happening in the production area once you bring in the pigs. If you give adequate rest after hog impact, it’s okay for there to be some rooting. But if there is significant erosion, rest will not restore the topsoil. Hogs left to their own devices can kill mature trees and turn a nice pasture into a moonscape. Also, too much manure in an area can damage water quality.

As for pasture and woodland, as stated above, for young pigs there won’t be a lot of nutritional benefit from the foraging. Older pigs can benefit greatly from the foraging and may consume very little purchased feed as a result. Again, you’ll have to test this out and realize that crops (pasture or forest or cropland) vary from year to year.

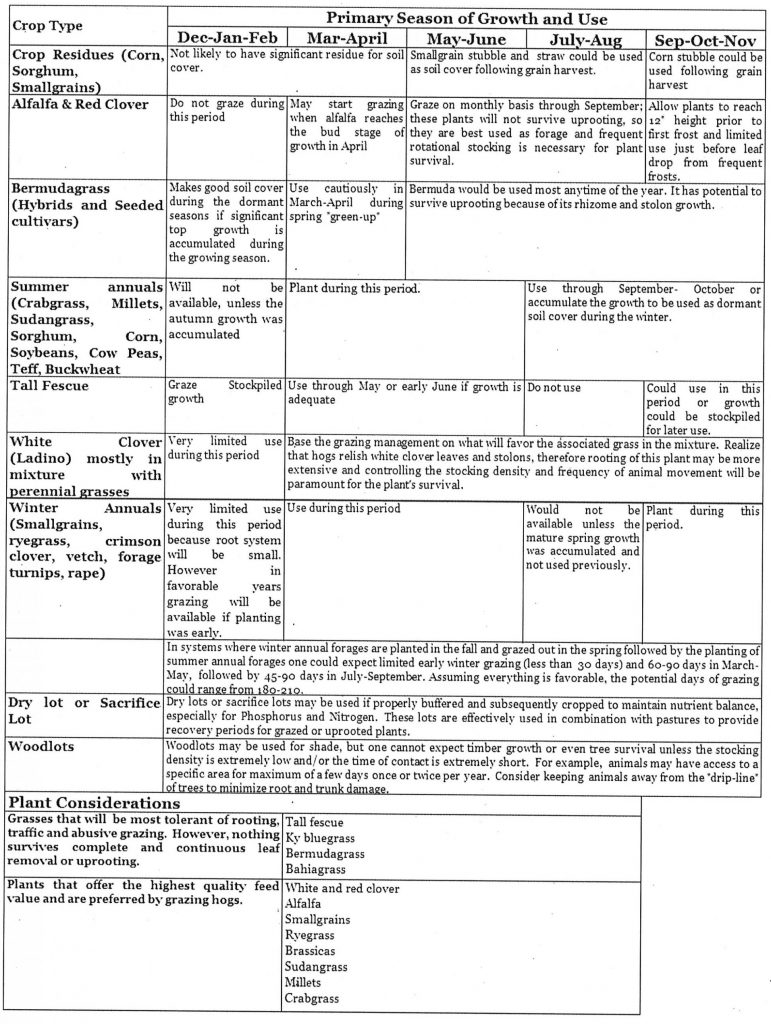

What kind of forages will be good for a pastured hog operation? To protect the soil, a tough plant that makes a dense sod is useful; bermudagrass or fescue, for example. But for palatability and nutritional quality, those are not the best choices. Whatever is already in place is the most cost-effective option, but perhaps there is an opportunity to try other forages. See Table 4 for some options to consider.

Of Limits and Lysine

One of the reasons many hog producers rely on purchased feed is that it is so easy to go wrong in formulating a diet for pigs. As stated previously, the needs change with the age of the animals, and gains will suffer if needs are not met. It’s beyond the scope of this publication to really explore hog nutrition, but here is a key concept: Animals can perform only as well as the level of the most limiting nutrient. The way this is often illustrated is with the barrel analogy.Picture a barrel with vertical staves. Some are as tall as the barrel, but some staves are cut shorter. Now, if you were to fill that barrel with water, how much could it hold? Only as much as the limiting stave, the shortest.

So it is with nutrition. Hogs need certain amino acids and in certain proportions. Lysine, in particular, is usually the limiting amino acid. Consequently, nutritionists balance hog diets with this in mind. If the hogs are not getting enough of the nutrients, they will not perform as well, and excess nutrients are often wasted. Picture the water running out of the barrel.

Because of the need for balanced nutrition, and because there are anti-nutritional factors in some feeds, there are limits to the amounts of some ingredients in a hog diet. Also, some ingredients cannot be used by pigs that are young. Before you decide to use low-cost ingredients, such as by-product feeds or local crops, be sure to check sources and do not exceed recommended amounts of a particular ingredient in the diet. You will also want to consider cost of the feedstuff on a nutrient basis. For example, brewers grains may be very inexpensive, but when you consider that they are mostly water, that changes the economics. For much more about swine nutrition, please see the Swine Nutrition Guide, Nebraska Cooperative Extension. The table on page 2 of the guide shows some common ingredients and the maximum amounts for various age groups.

Table 4. Crop Species and their Primary Season of Growth and Use by Hogs (Pietrosemoli et al., 2012).

Health

This simple hog shelter is portable and offers protection from sun, wind, and rain. Photo: Daniel Beal, Blackberry Hill Farm and Orchard

As with other livestock, first you must be careful to purchase pigs from a healthy herd, and that is best done by visiting the farm. Select only pigs that have these characteristics:

-

- A bright and clean haircoat

- Free and easy movement

- Good growth for their age (Klober, 1997)

Once you have acquired healthy stock, bring them home to a clean, low-stress environment. This will include the following:

-

- A pen that has had time and sunshine to disinfect the area from previous livestock exposure

- Simple shelter that provides shade and a windbreak

- Bedding in cold weather, so the pigs can stay warm

- Clean water that they can access and not lay in

- Fresh, palatable feed that is balanced for their stage of life and is always available

- Space, so the pigs can exercise

These are the fundamentals. For the health of land and animals, the livestock need to be rotated so that ground cover is not destroyed and pigs are not ingesting internal parasite larvae. Moving the animals away and letting the pasture or wooded area recover (i.e., 40 or more days) is a critical practice to allow forage regrowth and to reduce parasite larvae.

These healthy pigs have room to roam, a good pasture, and plenty of feed available in a self-feeder. Photo: Margo Hale, NCAT

“We lost some to pneumonia. They need a nice, dry place to live. Raised on pasture, parasites are an issue. Woodlots work if you rotate: paddocks can help a bunch. With time, though, issues come up. Say you have a 4-acre lot with 60 hogs on it. They can be healthy maybe two to three months, but eventually, there is too much impact on the land and it becomes a big latrine. In a drought, you’ll need to spray water to settle the dust, otherwise there will be respiratory issues. We vaccinate for tetanus, and maybe we should for pneumonia. Really, our pigs have been very hardy.

As for parasites, we did rotations, except our farrowing area was not rotated.” —Jeremy Prater

Vaccinations may be needed in your area. Consult local hog producers and your veterinarian to find out what vaccinations are recommended.

Hogs may suffer from temperature extremes. In cold weather, providing bedding and shelter will help prevent piling: pigs that are too cold can pile up and smother the pigs on the bottom. In hot weather, a sprinkler, shade, and wallow are all useful. If a hog overheats, it can go into shock. This writer once sprayed (with cold water from a garden hose) a hog that had overheated; that killed the hog instantly. Don’t make that mistake!

Besides providing good feed and water and rotating animals, producers will want

to watch for signs of illness and take prompt action. Here are some tips from A Guide to Raising Pigs, by Kelly Klober:“Early in the morning and late in the day…soundness and respiratory problems should be most noticeable. Give your animals your full attention. Suspect trouble if animals are:

- Slow getting off their beds

- Eating less or not eating at all

- Looking drawn

- Developing diarrhea

- Acting depressed

- Vomiting

- Experiencing abortions or stillbirths

- Lame or walking stiffly

- Acting uncoordinated

- Among nursing pigs, seeming to be “poor doers”

Normal temperature for pigs is between 101 and 102°F. If you notice listlessness or any of the other signs listed, take a rectal temperature and then call the veterinarian. Taking prompt action will give better results (Klober, 1997).

Handling

Knowing how to manage pigs is important for their welfare, and also for producing quality pork. Stress has a negative effect on health and on meat quality. Here are some strategies for reducing stress and maintaining pork quality, from Niche Pork Production:

Pigs that are accustomed to gentle handling will be much calmer. Photo: NCAT

-

- Spend time with pigs to reduce their fear of humans.

- Be patient and quiet. Move slowly. Let the pigs set the pace.

- Pig behavior reflects the handler’s disposition. Stay calm.

- Keep pigs in a group. Isolation stresses pigs.

- Pigs follow other pigs.

- Work pigs early in the morning, particularly during hot weather.

- In hot weather, sprinkle pigs with water while in transit.

- Take pigs off feed, but not off water, about 12 hours prior to slaughter.

(Lammers et al., 2007)

Hogs are strong and quick. We use feed to encourage hogs into the trailer. Practicing ahead of time makes it less stressful. Never use electric prods or other harsh methods to get animals to do what you want them to do. Thinking about gate placement and having a sheet of plywood to hold helps in moving hogs and is less stressful for animals and humans.

Summary from Jeremy Prater’s experience:

- Start small.

- Choose farrowing or finishing, not both at first.

- Locate a great processor.

- Tell your story well and market direct to consumers.

- Think through the costs and potential returns to see if there will be enough margin.

- Plan for facilities that work well.

- Unless you are willing to work at marketing, don’t bother to raise hogs for sale.

Conclusion

The author stands with Jeremy Prater on the Prater farm after an NCAT Beginning Farmer workshop, admiring the Prater cattle. Many thanks to Jeremy for his assistance with this publication and with workshops he’s hosted or taught. Photo: NCAT

Throughout this publication, we have discussed topics that you will need to consider to be successful in raising pastured or forested hogs. In several sections, we have referred to economics. It should be clear by now that feasibility depends on several factors:

-

- Location: including climate and access to customers, feed supplies, and processors

- Feed: cost, quality, and freshness

- Labor: for production and marketing

- Breed choice: matching what your customer wants and working well in your system

- Marketing: venues and ability to reach and keep customers

- Customers: numerous enough and willing to pay the prices you need to make a profit; repeat business

- Infrastructure: to prevent feed waste, save labor, facilitate handling of feed, water, and stock

- Product: volume of product, price of product, and ability to sell it all

- Personality: enthusiasm, willingness to tell the story, energy and skill in reaching customers, positive interactions, customer service, attention to details in production and marketing, recordkeeping and financial skill, motivation, etc.

Of these points, assuming there is a processor, the main factor affecting your chances of success is the last one. Are you willing to develop the skills needed? Do you really want to raise and sell pastured or forested hogs? If you answer positively to these questions, then I believe you can. Begin with a test batch, track all your costs, process the pigs and note exactly what they yielded, and figure out what prices you need to charge to ensure profitability. Experiment with cooking and serving your own product, and then reach out to customers. It takes time to build a market of loyal customers, but that will be key to your survival. Invest time and energy in learning how to market, as mentioned previously.

This publication does not attempt to cover every topic possible. Please refer to the resources listed and reach out to us at ATTRA if there are still gaps. If interest is shown, we will write follow-up pieces, including one about the farrowing enterprise. To let us know what your needs are, please Ask an Ag Expert. Best wishes for your success!

Hogs: Pastured or Forested Production

By Linda Coffey, NCAT Agriculture Specialist

Published September 2020

© NCAT

IP585

Slot 609

This publication is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development.