Federal Working Lands Conservation Resources for Sustainable Farming and Ranching

By Jeff Schahczenski, Agricultural and Natural Resource Economist

Abstract

This publication introduces and explains federal working-lands conservation programs administered by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Farm Service Agency (FSA). The Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) and the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) are discussed in detail, with attention to understanding the application and implementation processes for these programs. Examples of how these programs can benefit farmers and ranchers are included.

Introduction

Anna and Doug Jones-Crabtree began farming in their early forties, wanting to return to their agricultural roots. They have benefited greatly from programs offered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). Now, with more than 9,600 acres of certified organic cropland, Anna and Doug base their success, in part, on their ability to successfully access federal conservation resources. Over the years, they have been awarded several Environmental Quality Incentive Program (EQIP) contracts through a special initiative to assist organic farmers and ranchers. They have also enrolled in the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP). As Doug explains, “Farming is the only thing I ever wanted to do. I believe farming is the most important avocation. I grew up on a farm that did not make it through the farm crisis of the ’80s and have been waiting for the right time and opportunity to return to the land ever since.” NRCS programs were critical to the couple’s ability to begin organic farming. As Anna relates, “The EQIP organic initiative came at just the right time for us, as we literally started our operation from scratch in 2009. The EQIP organic initiative provided additional financial support as part of our start-up package. Practices we are implementing include organic transition, nutrient management, pest management, flex-crop, cover crop, field borders, and seeding pollinator species. Because we were considered beginning farmers, we were able to be included in the beginning farmer set-aside for the EQIP program.”

This publication assists readers in understanding how they can capture benefits like these that help the bottom line and promote a more sustainable agriculture.

Federal Conservation Resources and Your Farm or Ranch

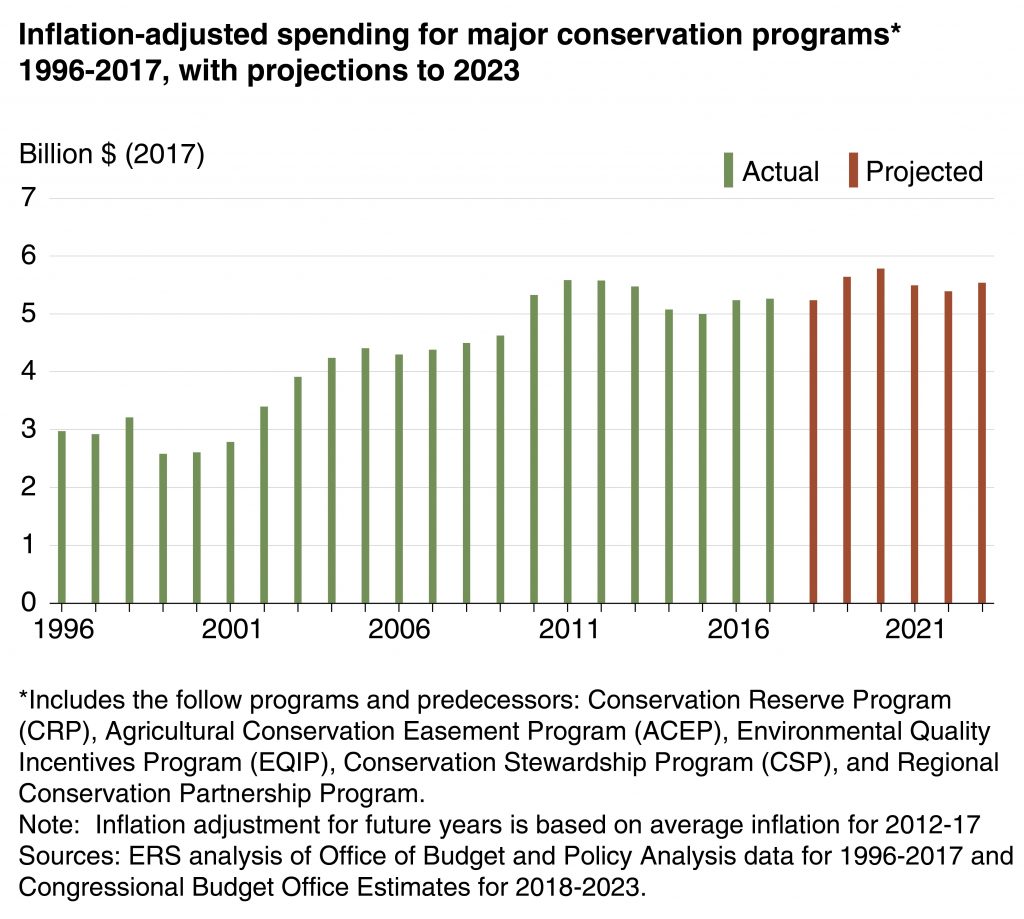

Figure 1. Source: USDA ERS

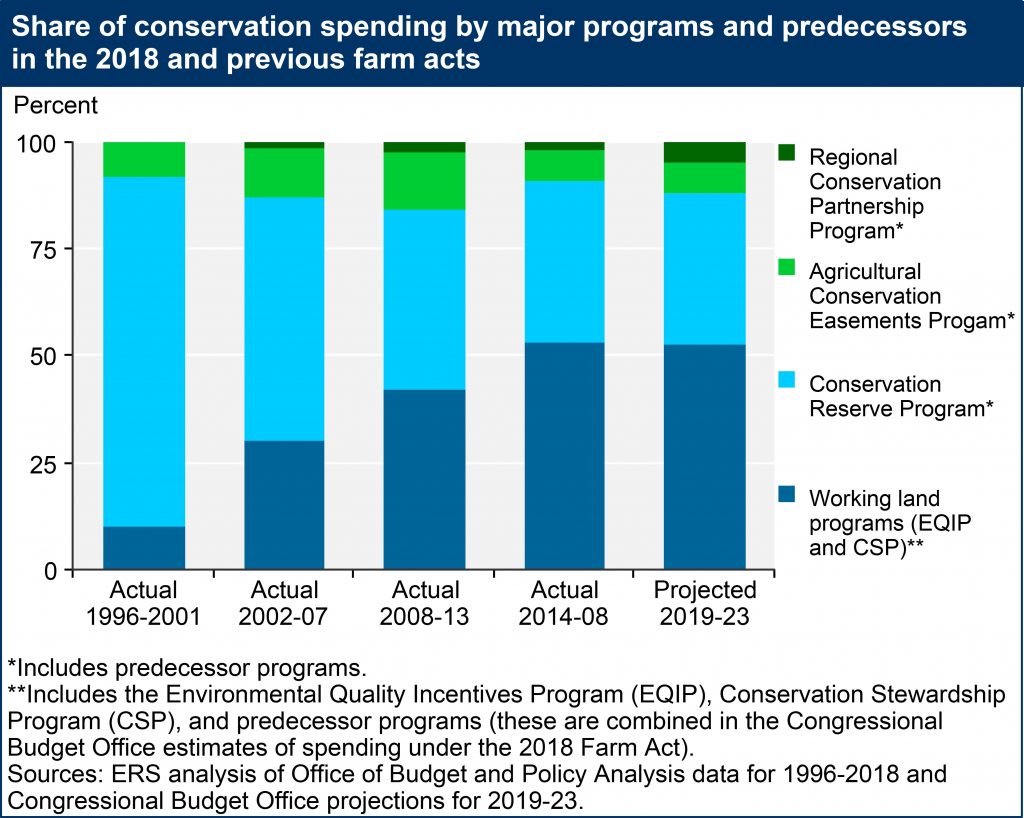

The federal government has provided significant benefits to American farmers and ranchers by both retiring marginal and environmentally sensitive lands and supporting the adoption of improved conservation practices on working lands. Figure 1 shows the actual and projected federal spending on major agricultural conservation from 1996 to 2023. Working-lands conservation increased from 1996 until 2018. It is projected to remain steady, making up about 50% of all agricultural conservation spending by the federal government (see Figure 2). Programs that support agricultural land preservation, conservation easement programs, and the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) make up the other half of federal spending on conservation. The Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) is a special program that works on a group-project basis. Learning how to take advantage of these important, but often complicated, programs can help farmers and ranchers lower production risks; provide tangible rewards for the contribution that conservation practices provide in improving soil, air, and water quality; increase profitability; and, in general, make farming and ranching more rewarding.

Another important reason to take advantage of federal conservation resources is that the application process itself helps farmers and ranchers see their operations from new perspectives. This can alert farmers and ranchers to new market opportunities and improve profitability and productivity. For example, transitioning to an organic production system on your farm or ranch may lead to higher value for your crops and livestock, as well as reduce environmental impacts of farming and ranching. Finally, farmers and ranchers can learn about and get technical assistance on conservation issues that the application process can identify.

Engaging in federal conservation programs can move your farm or ranch in a more sustainable direction. “Whole” farm or ranch planning—which assesses the goals and potential resources of the farm or ranch—will likely be necessary for farmers or ranchers interested in maximizing the benefits of these federal conservation programs. Even those unable to take advantage of a particular program should come away with a valuable learning experience through the very process of applying. Learning how federal conservation programs work and going through the application process usually helps farmers and ranchers better understand current innovative farming and ranching practices being adopted in their state or region. Also, farmers who engage in federal conservation programs can become more active citizens by making these programs work better for all farms and ranches in the community, state, and nation.

Finally, if you are identified as a historically underserved producer, these federal conservation-assistance programs offer a competitive advantage and/or higher levels of support. The definitions of these special categories are very specific, so make sure you meet the definitions and requirements before assuming eligibility (see Definitions box). When in doubt regarding eligibility requirements, check with the local office of the federal agency in charge of the specific program. You can find contact information for your NRCS state and local offices.

Definitions of Historically Underserved Producers

Limited-Resource Farmer or Rancher: A farmer or rancher who has a total household income at or below the national poverty level for a family of four, or less than 50% of county median household income in each of the previous two years. An online tool is available to make this determination.Beginning Farmer or Rancher: A farmer or rancher who has operated a farm or ranch for not more than 10 consecutive years and who will materially and substantively participate in the operation of the farm or ranch. Material and substantial participation requires that the individual provide substantial day-to-day labor and management of the farm or ranch, consistent with the practices in the county or state where the farm is located.

Socially Disadvantaged Farmer or Rancher: A socially disadvantaged group is one whose members have been subjected to racial or ethnic prejudice because of their identity as members of a group, without regard to individual qualities. A socially disadvantaged farmer or rancher is a member of the following socially disadvantaged groups: American Indians or Alaskan Natives; Asians; Blacks or African Americans; Native Hawaiians or Pacific Islanders; and Hispanics. For a farm or ranch entity, at least 50% ownership in the farm business must be held by socially disadvantaged individuals.

The term “entity” reflects a broad interpretation to include partnerships, couples, legal entities, etc.

Veteran Farmer or Rancher: A farmer or rancher who has served in the U.S. Military and was not released under dishonorable conditions. Also, the producer cannot have operated a farm or ranch for more than 10 years; or must have first obtained status as a veteran during the most recent 10-year period. A legal entity of joint operation can be designated as a veteran farmer or rancher only if all individual members independently qualify as veterans.

Figure 2. Source: USDA Economic Research Service (ERS), 2019.

What’s Available? Overview of Federal Conservation Resources

The complexity of federal conservation programs—and, in particular, the application process itself—is perhaps one of the biggest reasons many farmers and ranchers do not access these resources. The programs are voluntary, and many opt out of using them simply because the process can be difficult and intimidating. The programs contain an “alphabet soup” of acronyms and bureaucratic jargon that is particularly difficult for first-time applicants to understand. The goal here is to present a somewhat simplified overview that outlines the essential step-by-step process to access these resources and benefits. The intent is also to help you understand the general purpose of the programs.

Here, we specifically concentrate on resources available from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). This U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) agency is the one most engaged with agricultural conservation practices. The other major USDA agency involved in conservation efforts is the Farm Service Agency (FSA). Program responsibilities within these organizations often overlap. For example, the FSA shares administrative responsibility with NRCS for the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). The FSA also has responsibility for the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP), the Emergency Conservation Program (ECP), Farmed Wetlands Program (FWP), Transition Incentive Program (TIP) and the Emergency Forest Restoration Program (EFRP). Table 1 below provides an overview of the major conservation programs.

Table 1. Major Federal Conservation Programs as of Passage of the 2018 Farm Bill |

||

|---|---|---|

| Natural Resources Conservation Service NRCS) | Environmental Quality Incentive Program (EQIP) | Financial support for specific conservation improvements and meeting regulatory requirements. Variable levels of financial support, depending on practices implemented. Maximum financial support is set at $450,000 per farming operation. (EQIP contracts related to certain farms organized as general partnerships, as well as farms in particular irrigation districts, may be eligible for a maximum of $900,000. Ask your local NRCS if you qualify.) |

| Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) | Financial support for current conservation performance and future improvements based on broad land-use categories (cropland, grassland, rangeland, and non-industrial private forest land). Maximum financial support is $40,000 per year for five years or a maximum of $200,000. Farmers and ranchers can apply for an additional five-year contract. (CSP contracts with a special joint-operations business type may have a contract limit up to $400,000 over the term of the initial contract period. Ask your local NRCS if you qualify.) | |

| Water Bank Program (WPB) | A three-state program (Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota) to keep water on the land for the benefit of migratory wildlife, such as waterfowl. | |

| Agricultural Management Assistant Program (AMA) | A 16-state program for financial and technical assistance to improve water management or irrigation structures. Variable levels of support, depending on project. |

|

| Farm Service Agency (FSA) and NRCS | Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) | Annual payments to keep sensitive land out of agricultural production. |

| Farm Service Agency (FSA) | Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) | Annual payments to keep riparian areas out of agricultural production (requires state matching funds). |

| Emergency Conservation Program (ECP) | Funding for rehabilitating farmland damaged by natural disasters and for carrying out emergency water-conservation measures in periods of severe drought. | |

| Emergency Forest Restoration Program (EFRP) |

Financial and technical assistance to owners of non-industrial private forestland damaged by natural disaster, to carry out emergency measures to restore damaged forests and rehabilitate forest resources. | |

| Farmable Wetlands Program (FWP) |

Designed to restore previously farmed wetlands and wetland buff er to improve both vegetation and water flow. Run through the CRP (above). | |

Conservation Programs: Planning and Application

The first step in accessing these federal resources can begin with the development of a comprehensive conservation plan by NRCS. Such a plan may be useful, but it is not mandatory for application. An NRCS conservation plan is helpful because it engages NRCS staff early in the process. Even if you have done prior planning, it is still important to get NRCS assistance in translating your existing planning efforts into agency language and structure. The local NRCS agent can evaluate the programs and practices available to you and suited to your needs.

Although this may be the ideal process, finding available NRCS local staff to assist with this kind of planning can often be difficult. The actual process begins with a farmer or rancher contacting the local NRCS field staff office about a specific conservation program. The conservation planning continues with a discussion of the application process and eligibility requirements for the specific program(s). Preparing in advance by understanding the basics of the programs is valuable because it is important to fully grasp the benefits and limitations of the financial and technical assistance available.

Beginning in early 2020, NRCS attempted to ease planning and application procedures through the development of a new ranking tool called the Conservation Assessment Ranking Tool (CART). This tool assesses natural resource concerns, planned conservation practices, and farm-site vulnerabilities and ultimately ranks the application for funding for both CSP and EQIP. It is a complicated tool, combining planning and program applications. The goal is to simplify both the planning and application process. Details of the CART process will be discussed below.

Finally, another improvement in accessing conservation programs has been the introduction of the Client Conservation Gateway system. This allows farmer and rancher applicants to do much of the paperwork for application and reporting on financial assistance programs online. There is a somewhat cumbersome process to establish a client account, but once that’s done, this system can make application paperwork efforts easier, at least for those with good Internet access. Details are available at the NRCS Client Conservation Gateway System.

Know the Programs: Working Land vs. Retiring Land

Federal conservation programs can be divided into two broad categories: working-lands programs and land-retirement or easement programs.

Working-lands programs provide financial resources for farmers or ranchers to implement particular practices, conservation structures, enhancements, and bundles of practices on working agriculture lands. NRCS offers extensive information on quality criteria for managing natural resources to help in assessment and planning of future conservation efforts.

Understanding these technical standards can be complicated for many people who are not familiar with NRCS protocols and jargon. However, if you are serious about taking full advantage of the programs, some understanding of these standards and the systems of resource management that underlie them is important. The major resource that offers help in understanding technical standards and the general program-evaluation processes is the Field Office Technical Guide (FOTG). This document is available online at as the eFOTG.

This system is “localized” down to the state—and sometimes county—level, so obtain the copy relevant to your farm or ranch locale. The NRCS prides itself on soliciting local input for program development. Consequently, there is some variation among available programs across states and even counties, particularly for working-lands programs.

Land-retirement or easement programs, on the other hand, are those that pay farmers or ranchers to keep land out of agricultural production either permanently or temporarily. Some programs do allow specific productive uses of easement land, but generally these programs were established to take land out of substantial agricultural productive use for environmental and wildlife benefits. These programs are not discussed in detail in this publication.

National vs. State: Differences in Program Details

As noted, program details can change significantly from state to state and even county to county. The logic behind this approach makes some sense. Land use for agriculture varies dramatically between different parts of the country. For instance, the best conservation grazing management practices for southwest Montana are substantially different from those in central Florida. On the other hand, local determination of program criteria is often a source for confusion about what working lands programs can and do offer. In Montana, for instance, some NRCS programs provide resources for ranchers to improve fish passage around irrigation diversions. But the programs apply only to certain areas of the state, despite the fact that most areas have important fish-passage issues. The best way to avoid confusion is to go to the respective state NRCS website to look up specific details of a program for that state. Another way to clear up confusion is to talk with local and state-level NRCS staff.

Working-Lands Programs

Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP)

This program is unique because it rewards farmers and ranchers for current conservation efforts and for putting in place additional new conservation practices and enhancements over a five-year contract period. The program takes a whole-farm or ranch approach, rather than a specific practice-by-practice perspective. The program allows farmers and ranchers to apply at any time, but assessment and award of a CSP contract in any particular federal fiscal year begin after a specific deadline announced by NRCS, and these deadlines vary by state. Remember, the federal fiscal year ends in September, so the conservation contracts need to be awarded by the end of the fiscal year. For example, for the 2020 crop year, the deadline for CSP assessment was June 12, 2020, in Montana. This means that any CSP applications made prior to that date would be considered for funding in FY 2020. If you apply after that date, your application will be held and evaluated in the next program year. Unfortunately, the CSP application deadline changes from year to year and state by state, so you will need to check with your local NRCS office for relevant CSP application cut-off deadlines.

The CSP program was significantly changed by Congress in 2018 with the passage of the Agricultural Improvement Act, or what is called the 2018 Farm Bill. The most important change was that CSP is now based on a set overall funding level, rather than on a per-acre payment basis. In short, funding amounts are fixed in each state, and applications are ranked and funding allocations distributed to the higher-ranking applications until funding is exhausted. In general, CSP is an over-subscribed program, meaning there are more dollars requested in applications than available in the program. Thus, CSP is a truly competitive program for those seeking support. Below is a basic step-by-step outline for application, with important information and forms that can help in getting ready to apply for this program.

Step 1: Make initial application

The basic application form is available through the CSP website.

If you have NOT accessed federal agriculture funding in the past, or are a brand-new farmer or rancher, you will need to establish yourself as a legal farm by registering with the Farm Service Agency (FSA) and acquiring a Federal Farm ID number. NRCS and FSA field offices are usually located together in what is known as a Farm Service Center. It might be worth setting up an appointment with your local FSA office, and you will need copies of your Social Security number and property deed(s) or lease agreement document(s).

Some additional forms will likely be needed to establish basic eligibility:

- AD-1026 Highly Erodible Land Conservation and Wetland Conservation Certification (available at local NRCS offices)

- CCC926 Adjusted Gross Income Certification (available at local NRCS office)

Important NRCS Conservation Definitions

Land Uses: Cropland, forestland, pastureland, and rangeland

Resources of Concern: The major “resources of concern” categories considered by NRCS are Soil, Water, Air, Plants, Animals, and Energy. Resource concerns relate to possible problems or impacts farming or ranching may have on the resource. In the case of soil, for example, wind erosion could be a possible concern impacting the soil resource. There are a total of 47 possible resources of concern currently evaluated by the CART, and these relate to specific sub-categories of the major resources of concern. For example, in the case of plants, resources of concern include plant productivity and health, plant structure and composition, plant pest pressure, and wildlife hazard from biomass accumulation.

Stewardship Threshold: The level of management required, as determined by the NRCS, to conserve and improve the quality and condition of a natural resource. NRCS has many methods for making such determinations, and they are essentially embedded in the CART.

Step 2: Ranking and the Conservation Assessment Ranking Tool

After initial sign-up, and after establishing eligibility and completing the basic application, the next step will be to work with local NRCS staff to establish a ranking score. As mentioned earlier, NRCS staff will use a software tool called the Conservation Assessment Ranking Tool (CART) to determine this. This tool is used to evaluate an applicant’s conservation performance, based on past and current efforts, as well as the activities proposed during the five-year contract period. Each CSP applicant must meet what is called the “stewardship threshold” for a least two resources of concern on each land use as determined by the CART (see box for definitions). Finally, to be eligible for possible funding, the applicant must also agree to address one additional resource concern by the end of the contract for each land use identified in the application.

After the assessment part of the CART is explored and explained to you by NRCS, you can consider a number of additional conservation practices, enhancements and/or “bundles” of enhancements and practices to adopt during the proposed five-year CSP contract. (See text box for details.) The list of practices, enhancements, and bundles is extensive and should probably be reviewed in advance of the ranking process. Unfortunately, what is available to the applicant is different in every state. For online access to what is available in your state, you must go to the respective state NRCS website and go to the financial assistance link available for CSP.

As an example, the financial assistance page for the CSP for the Texas NRCS. However, this link does not provide easy access to what specific CSP practices, enhancements, and bundles are available from NRCS in Texas. Unfortunately, state NRCS websites are not uniform, so it takes a bit of exploration of your state’s site to find these details. Of course, alternatively, you can visit or call your local NRCS office and simply ask for the lists of practices, enhancements, and bundles available for CSP in your state.

Examples of CSP Practices, Enhancements, and Bundles

Practices: NRCS has hundreds of conservation practices with detailed specifications on how to implement and estimates of costs for implementing. Each state NRCS office selects a subset of these that are then available for support through the CSP. One example of a conservation practice is the use of cover crops.Enhancements: These are conservation activities that treat a natural resource concern and generally improve conservation performance. Enhancements exceed the basic minimum requirements of conservation practices. For example, the soil health crop-rotation enhancement includes efforts to increase diversity of the cropping system, maintain crop residues throughout the year, keep living roots in the soil, and minimize chemical, physical, and biological disturbances to the soil. Details of the enhancements can be found at: CSP Enhancements & Bundles.

Bundles: These are groupings of practices and enhancements, generally around a single resource of concern. An example is the Soil Health Assessment Bundle, which incorporates six separate conservation practices to create a “synergy” of activity that goes beyond adoption of any single specific soil health conservation practice. Details of the bundles can be found at the link above.

Step 3: Optimizing Ranking: Priority Resources of Concern

Though the CSP has a broad mandate to enhance and improve all natural resources of concern, the program allows each state NRCS office to identify five priority resources of concern. These state priorities will heavily impact how your application will be ranked in your state and how likely it is that your application will be supported. Thus, before making any decisions on what new conservation activities you will undertake, it is critical to find out the priority resources of concern for your state. Again, you can contact your local NRCS office or look for that information on your state’s NRCS website.

To see how priority resources concerns matter, consider the example of California. California NRCS has chosen the following five resource concerns for the 2020 application year:

- Air quality emissions

- Degraded plant condition

- Field pesticide loss

- Livestock production limitation

- Terrestrial habitat

After carefully reviewing your CART analysis with NRCS and exploring new activities you could undertake, you may decide that improving soil health is important to your farm or ranch. How could these state priority resource concerns help you in reaching such a general goal? The short answer is not very much, since none of these, with the possible exception of degraded plant condition, directly refer to improving soil health, and because soil resources of concern are not a priority for the NRCS in California in 2020. Thus, your application will likely not rank highly enough to be funded, given that applicants who address priority resources of concern will rank higher. This does not mean you cannot apply for support for improving soil health—it is just that your probability for support will be lower. In this case, you might want to consider alternative conservation-related problems that also may be of importance to you and that will fit within the priority resource concerns of the state. You can and should ask the local NRCS staff to look at various options and scenarios and explore them with the CART.

In addition to understanding how the state-adopted priority resources of concern impact your ranking, it is also important to understand which ranking pool you are participating in. All states have distinct ranking pools for socially disadvantaged and veteran farmers and ranchers, organic farmers and ranchers, and beginning farmers and ranchers. In addition, some states subdivide the state into geographic regions that represent separate ranking pools. It is important to note that when you are assigned to a specific pool, you are only competing with the other farmers and ranchers in the respective pool, rather than with all applicants statewide. Depending on how your state NRCS allocates available funding between the ranking pools, the competition for funding will vary.

This is a recorded, three-part ATTRA webinar series available to help you better understand the process of using the Conservation Assessment and Ranking Tool.

Step 4: Work out contract payments and details

Payment amount will be determined based on three factors:

- Existing activity payment: payment to maintain the existing conservation, based on the land uses included in the operation and the number of resource concerns that are meeting

the stewardship threshold level at the time of application - Additional activity payment: payment to implement additional conservation activities

- Supplemental payment: payment for adopting or improving a resource-conserving crop rotation or advanced grazing management (optional)

Overall, CSP payments vary by land type, the extent of existing conservation efforts that will be managed and maintained, and the extent of new conservation practices and activities to be implemented. It is important to note that the CSP does not pay for the full cost of either maintaining or taking on conservation efforts. So, be very clear what your financial commitments are in undertaking a CSP contract. Each state’s payment rates for conservation activities vary and can change every year. The payment rate schedule for your state can be found by asking your local NRCS office.

Also, the relative importance of these three factors is variable, regarding their impact on application ranking. In general, undertaking new conservation activities weighs more heavily in improving the ranking of your application. Individual CSP payments depend on the details of each contract. Payments to contract holders will be made after October 1 of the year the conservation has been accomplished (i.e., if the terms of the contract are fulfilled during the spring and summer, the accompanying payments will be made in the fall).

Contract, Field Verification, and Conservation Stewardship Plans

As part of contract development for each successful applicant, NRCS is required to visit each applying farm and ranch to verify information provided in the application. In addition, the development of a conservation stewardship plan is required. A conservation stewardship plan is defined as a record of the participant’s decisions that describes the schedule of conservation activities to be implemented, managed, or improved during the contract life.

Specialty Crops, Organic Production, and Technical Assistance

The implementation rules for the new CSP commit NRCS to make a special effort to provide technical assistance to organic and specialty crop producers. Though it’s a bit dated, NRCS has provided The Organic Crosswalk to help organic farmers and ranchers applying to the CSP program. This document offers an explanation of how producers can use CSP Conservation Enhancements to aid them during the “transitioning” period to organic farming. The Organic Crosswalk is available online.

Resource-Conserving Crop Rotations

In the CSP, special emphasis and supplemental funding are available for applicants who undertake a resource-conserving crop rotation. The understanding of what constitutes such a rotation is still less than clear and will require careful discussion with NRCS field staff.

Grasslands Conservation Initiative

This is a new initiative introduced with the passage of the 2018 Farm Bill. It is specific to farmers and ranchers wishing to protect grazing land uses. See your local NRCS field staff for details to determine if this would be a useful addition to your CSP contract.

Table 2. National EQUIP Initiatives |

|

|---|---|

| Air Quality Initiative | Provides financial assistance to implement approved conservation practices to address significant air-quality resource concerns for designated high-priority geographic locations throughout the nation. |

| On-Farm Energy Initiative | Enables the producer to identify ways to conserve energy on the farm through two types of Agricultural Energy Management Plans (AgEMP): for headquarters and/or for landscape, also known as an on-farm energy audit (headquarters and/or landscape); and by providing financial and technical assistance to help the producer implement various conservation practices recommended in these on-farm energy audits. |

| Organic Initiative | Provides financial assistance to help implement conservation practices for organic producers and those transitioning to organic, to address natural resource concerns. Also helps growers meet requirements related to National Organic Program (NOP) requirements and specific program payment limitations. Funding is limited to $140,000 over the five years of the 2018 Farm Bill authorization (2019-2023). This is much less than the EQIP generally. |

| National Water Quality Initiative | Helps farmers and ranchers implement conservation systems to reduce nitrogen, phosphorous, sediment, and pathogen contributions from agricultural land in specific approved watersheds. Contact your local NRCS field office to see if you are eligible. |

| Colorado Salinity Control | Helps producers in this river basin reduce salinity by preventing salts from dissolving and mixing with the river’s flow. Different states within the river basin apply varying criteria. Contact your local NRCS field office to find out more. |

| High Tunnel Initiative | Helps producers plan and implement seasonal high tunnels, which are steel-framed, polyethylene-covered structures that extend growing seasons in an environmentally safe manner. |

Environmental Quality Incentive Program (EQIP)

The Environmental Quality Incentive Program (EQIP) is the largest NRCS working-lands program, with an annual budget expected to be over $1.75 billion through 2023. The general purpose of EQIP is to promote agriculture production and sound forest management while encouraging environmental quality and benefits. As of the 2018 Farm Bill, EQIP applicants can now include water-management entities such as state irrigation districts for projects supporting water conservation and irrigation efficiency. Also, as of the 2018 Farm Bill, historically underserved participants (see definitions) can get advance payments to offset costs of implementation of conservation practices upon award of an EQIP contract.

EQIP has also provided substantial federal resources to assist farmers and ranchers to stay in compliance with regulations regarding the operation of Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) and Animal Feeding Operations (AFOs). This has raised controversial issues involving large-scale dairies and commercial feedlots. NRCS is currently required to try to achieve a target of 50% of EQIP expenditures for livestock conservation practices. Although not all of that livestock-related EQIP funding has gone to resolve CAFO/AFO issues, a large percentage has.

Despite these environmental regulatory aspects to EQIP, there have been many farmers and ranchers who have improved conservation practices and their bottom lines by participating in this program. EQIP has from time to time allocated resources to special initiatives.Currently (2020) there are six national EQIP special initiatives, as shown in Table 2. Also, each state NRCS has additional state-based EQIP initiatives that may be important to review prior to application. Check with your local NRCS office or website about special state-based EQIP initiatives.

EQIP is a very competitive program that is under-funded relative to demand by farmers and ranchers. This means that to make your application more competitive, you might want to develop a comprehensive plan of the conservation practices integrated into your farm and ranch before you apply. Also, pay close attention to which elements of your plan fit with the priorities that NRCS has identified as important for funding in your state and for the year you wish to apply. Below is a basic step-by-step outline for application, with important information and forms that can help in getting ready to apply to this program.

Step 1: Make initial application

The basic application form for EQIP is the same as for the CSP. This form is available online through the NRCS EQIP website as EQIP NRCS-CPA-1200.Again, if you have NOT accessed federal agriculture funding in the past or are a brand-new farmer or rancher, you will need to establish yourself as a legal farm by registering with the Farm Service Agency (FSA) and acquiring a Federal Farm ID number. NRCS and FSA field offices are usually located together in what is known as a Farm Service Center. Some additional forms will likely be needed to establish basic eligibility:

- AD-1026 Highly Erodible Land Conservation and Wetland Conservation Certification (available at local NRCS offices)

- CCC926 Adjusted Gross Income Certification (available at local NRCS offices)

As with the CSP, EQIP applications can be submitted to NRCS at any time; however, like CSP, there is a deadline after which your application will be pushed forward to the next fiscal year. Unfortunately, the EQIP deadline varies from state to state and often changes from year to year, so, again, check with your local NRCS office or the state NRCS website for the EQIP deadline in your state.

Finally, note that the EQIP deadlines can be quite early in the fiscal year. For example, the deadline for fiscal year EQIP applications in Montana was March 13, 2020. That means that within the first three months of the calendar year, your application would still be considered for funding within that year. Past that date, your application would be rolled over into the next fiscal year.

Step 2: Ranking and the Conservation Assessment Ranking Tool

EQIP benefits are determined by an NRCS evaluation of the farmer’s or rancher’s application against a set of funding priorities known as “ranking criteria.” For EQIP, these are embedded in the Conservation Assessment Ranking Tool (CART). These criteria are set at the national, state, and even county levels. The NRCS gets advice on setting these priorities from two governance committees: the state technical advisory committee (state-level) and the “local working groups.” (See the conclusion for more information on how these groups provide input.)

Thus, each state’s set of priorities is distinct and, in any given year, may not reflect the needs you have identified in your planning efforts for your farm or ranch. However, there is often a fairly wide variety of conservation practices available to applicants and it may be hard to tell without going through the CART process how your planned changes will be “ranked.” Also, the CART process can vary by where your farm or ranch is located, as the ranking criteria embedded in the CART vary based on the specific resource concerns identified for your location.

Step 3: Optimizing EQIP Ranking: Priority Resources of Concern

To provide an example of how the ranking process works and how to optimize benefit from an EQIP contract, consider the process from the perspective of a farmer in Cameron County, Texas. Note that this example is specific to NRCS in Texas, and the process described here will vary to some degree from state to state.

Priority Resource Concerns for Edinburg, Texas, Resource Team

Non irrigated cropland (1): Soil—Sheet and rill erosion

Non irrigated cropland (2): Soil— Wind erosion

Non irrigated cropland (3): Soil— Organic matter depletion

Irrigated cropland (1): Water—Inefficient irrigation water use

Irrigated cropland (2): Water—Salts transported to surface water

Irrigated cropland (3): Soil—Sheet and rill erosion

Pastureland (1): Animal—Feed and forage imbalance

Pastureland (2): Water—Inefficient irrigation water use

Pastureland (3): Animal—Inadequate livestock water quantity, quality, and distribution

Rangeland (1): Plant—Plant productivity and health

Rangeland (2): Animal—Inadequate livestock water quantity, quality, and distribution

Rangeland (3): Plant—Plant structure and composition

Forestland (1): Not Applicable

Forestland (2): Not Applicable

Forestland (3): Not Applicable

EQIP in Cameron County Texas, Fiscal Year 2021

Texas NRCS has determined priority resources of concern for EQIP application based on what Texas calls NRCS Resource Teams. There are 48 NRCS Resource Teams in Texas and these represent groups of Texas Soil and Water Conservation Districts. (Many of the Texas Soil and Water Conservation Districts are county-based, but some overlap several counties. For more details, see www.tsswcb.texas.gov/swcds.) In the case of a farmer in Cameron County, Texas, the Edinburg NRCS Resource Team establishes priority resource concerns. For Fiscal Year 2021, the Edinburg NRCS Resource Team has determined three priority resources of concern for each of the different land uses (non-irrigated cropland, irrigated cropland, pastureland, and rangeland). The box at right provides the list of these priority resources of concern.

What this list tells the EQIP applicant in Cameron County, Texas, who is pursuing EQIP support is that an application pursuing conservation efforts not on this list will likely be ranked lower, compared to applications addressing these priorities. So, for example, if the applicant wanted to pursue conservation efforts involving forestlands on the farm or ranch, then the application would likely rank low and funding would be less likely.

However, it is also important to understand that even if particular conservation measures prioritized locally are relevant to the applying farmer or rancher, there is still no guarantee that the producer will ultimately be provided EQIP benefits. This is true because the applicant is still competing with every other applicant statewide. Also, as noted earlier, there are often distinct funding pools that relate to special EQIP national and state initiatives. For instance, if a farmer or rancher is applying for EQIP funding under the Organic Initiative, that producer would only be competing with other organic EQIP Organic Initiative applicants, because this initiative is funded out of a separate funding pool.

What this example also shows is that applying for EQIP benefits is a little like applying for a grant. The grantor (NRCS) gets to decide the criteria for grant awards, and the producer applicant who best matches those criteria has increased probability of obtaining the grant. The CART is the major means for assessing the degree to which a given applicant matches the grant criteria.

In addition, note that an application for a single practice change is less likely to be funded than an application for multiple changes. It is useful to have a holistic plan of all the conservation-related changes you wish and can afford to make on your farm or ranch and then apply to implement the changes that best match the local priorities.

The benefits of an EQIP contract can be substantial, but obtaining one requires real work and financial commitment by the applicant farmer or rancher. Again, careful planning and optimization of program criteria are critical for success.

EQIP High Tunnel Initiative and NCAT’s SIFT Farm

The National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT), which created and operates the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture Program, has a long-term Small-Scale Intensive Farm Training (SIFT) demonstration farm to help communities everywhere increase food security by producing healthy food. In 2017, the SIFT farm applied for the EQIP High Tunnel Initiative and, after going through the yearlong application process, was supported in the development of two seasonal high tunnels. Montana NRCS provided $12,500 toward the purchase and establishment of these high tunnels. High tunnels are an enclosed covered structure at least six feet high that protect crops from sun, wind, excessive rainfall, or cold. The resource of concern addressed is plant health and vigor. See the ATTRA publications SIFT 2018: Lessons from a Small-Scale Urban Intensive Farm, and SIFT 2019: Continuing Lessons from a Small-Scale Urban Intensive Farm to learn more.

Implementation of EQIP and CSP Contracts

Being awarded an NRCS working-lands conservation program contract is only the beginning of the process. NRCS working-lands contracts are legally binding and commit you to fulfilling your end of the bargain. With contracts lasting in some cases 10 years, it is important to be absolutely clear on your commitments. By the same token, NRCS has also made significant commitments. During the implementation phase, you will need to work regularly with your local NRCS agent to make sure you are making timely progress on your contract.

It is possible that disputes may arise about either the fairness of the application process or about your obligations during the implementation of the contract. Federal law does provide for a formal process of appeal. Although NRCS works hard to make sure you understand the details of a program contract prior to implementation, knowing your rights for appealing decisions is important.

Appeals

The appeals process—like the programs themselves—is complex. The first question to be clear about is the basis for your appeal. For instance, if you appeal the rejection of your application for program benefits, remember first that the programs are competitive and that losing in competition is not itself a reason to appeal. The general basis for an appeal includes the following:

- Denial of participation in a program

- Compliance with program requirements

- The payment or amount of payments or other program benefits to a program participant

- Technical determinations or technical decisions that affect the status of land even though eligibility for USDA benefits may not be affected

There are specific reasons that an appeal can be rejected by NRCS:

- General program requirements applicable to all participants; that is, you cannot make your farm or ranch a “special” case.

- Science-based formulas and criteria; for example, eligibility for CSP could be based on a certain minimum scoring as likely demonstrated by the CART analysis. You cannot appeal your eligibility on the basis the CART analysis used the wrong criteria for evaluation. However, if you think the wrong information was used in the CART analysis, then an appeal may be warranted. At a minimum, it should be clear to you how the CART analysis was done and that the information used was correct.

- The fairness or constitutionality of federal laws; for example, arguing that it is unfair because you think the CSP should provide greater than $40,000 per year for your conservation efforts is not the basis for an appeal. However, you should expect NRCS to make it clear to you exactly what they are supporting you to do.

- Technical standards or criteria that apply to all persons

- State Technical Committee membership decisions made by the State Conservationist

- Procedural technical decisions relating to program administration

- Denials of assistance due to the lack of funds or authority

Once you have established a basis for an appeal, determine whether you are appealing a “technical determination” or a “program decision.” An appeal of a technical determination challenges the correctness of “the status and condition of the natural resources and cultural practices based on science and best professional judgment of natural resources professionals concerning soils, water, air, plants, and animals.” For example, the stocking rate of cattle on a particular range or pasture could be a contested technical decision.

An appeal of a program decision, on the other hand, challenges the correctness of the determination of eligibility, or how the program is administered and implemented. For example, if the local NRCS field staff entered information incorrectly into the CART in assessing your application to the CSP, then you could appeal on the basis of this error.

After you have decided the basis for an appeal and the type of appeal, the next step is to make sure the program you applied for is a “Chapter XII” program. Chapter XII refers to the title of the Food Security Act of 1985, where the current appeals process was established. All the programs outlined in this publication are Chapter XII programs. Check with your local or state NRCS office for a list of non-Chapter XII programs.

To begin the preliminary phase of the appeal process, ask in writing for one of three actions to take place within 30 days after notification of the decision you wish to contest.

- Make a request for a field visit and reconsideration of an NRCS decision.

- Ask for mediation of the contested decision.

- Appeal directly to the local Farm Service Agency (FSA)—usually county-based—for a reconsideration of a decision.

Which of these three routes to take in the appeals process is up to you. It may be hard to evaluate which is of greatest benefit. Even though the first choice explicitly provides for a “field visit,” all others will require a field visit anyway. The reconsideration and mediation routes should be completed within 30 days of the request.

Finally, even after these appeal routes are exhausted, you can still appeal a decision to the National Appeals Division (NAD) of the USDA. This agency is independent of the other USDA agencies and provides participants with the opportunity to have a neutral review of an appeal. The NAD can make independent findings but also must apply laws and regulations of the respective agency to the case.

Conclusion

The working-lands conservation programs outlined in this publication are complex; accessing these resources requires significant effort and an investment in time and energy by producers. The complexities of the programs are in part due to sincere efforts by a large federal agency to make the programs locally relevant and to assure careful expenditure of federal resources. If you do not like the way programs are designed and implemented, the NRCS is unique in that it also provides at least two ways for you to be engaged in changing them.

Local Working Groups

Local Working Groups are essentially a form of local governance of federal conservation programs. Their meetings are open to the general public, but formal membership is limited to federal, state, tribal, or local government representatives. The meetings are convened by the local conservation district and the purpose of the group is to provide advice to the NRCS on conservation programs. Contact your local NRCS office about the meeting schedule in your area. As a farmer or rancher, you can attend these meetings and offer public comment on the decisions being made. Incumbents of any of several local government offices usually serve as leaders of these groups. The Local Working Groups also provide representatives to serve on a multi-state committee. The working groups provide advice in the following general areas:

- Conditions of the natural resources and the environment

- The local application process, including ranking criteria and application periods

- Identifying the educational and training needs of producers

- Cost-share rates and payment levels and methods of payment

- Eligible conservation practices

- The need for new, innovative conservation practices

- Public outreach and information efforts

- Program performance indicators

State Technical Committees

Each state NRCS office has a State Technical Committee (STC). The committee is comprised of groups or individuals who represent a wide variety of natural resource issues. If you wish to serve on your STC, either as an individual or as a representative of a group, you must write a letter to your State Conservationist explaining your interest and credentials. Several federal agencies must be represented on the committee by law and many non-governmental and state agencies are encouraged to participate, as well. Unlike local working groups, STC members do not have to be “elected” officials. Public notification of meetings must be accomplished no later than 14 days prior to the meeting, and the state conservationist is required to prepare meeting agendas and necessary background information for the meetings. There is no requirement for any number of meetings in any given year, but any USDA agency can request that a meeting be held.

The STC has the purpose of providing recommendations on conservation activities and programs in the state. However, it is important to remember that the STC is only an advisory body and has no legal enforcement or implementation authority. Nonetheless, even without statutory authority, members of the STCs are generally the leaders of agriculture in a particular state. It would be difficult for any State Conservationist to not give strong consideration to the recommendations of this important group.

Final Word: Is Conservation a Public Good?

There are some farmers, ranchers, and agricultural and conservation organizations who have had philosophical issues with the very intent of working-lands conservation programs. For example, the CSP concept of rewarding farmers and ranchers for their ongoing conservation efforts is fundamentally different from all other federal conservation programs. Some have argued that if some farmers and ranchers are already providing these benefits without public support, then why should scarce public resources be provided to continue these efforts (Batie, 2006)? Others have argued that good stewardship by farmers and ranchers provides a public good or investment. It is argued that we all benefit from these stewardship efforts, and that public incentives are required for continued good stewardship of the land and, more importantly, to encourage those who do not provide these public benefits to consider them (Kemp, 2005).

EQIP supports farmers and ranchers in moving toward improved conservation practices that protect natural resources and the environment. The immediate additions to social benefits seem clearer than with CSP. However, EQIP also has a role to regulate environmental damages resulting from agriculture by changing farming and ranching practices that damage the environment or degrade natural resources before governmental enforcement actions are imposed. In this regard, EQIP is often criticized for rewarding the worst environmental actors in the agriculture system.

These issues, like many others in our democratic system, strike at the broader issue of the proper role of government in protecting both the environment and the future productive capacity of natural resources. Even with the substantial federal-resource increases in conservation since 2002, federal conservation programs still only represent about 7% of all USDA expenditures. So, even at this higher level of activity, the federal government is far more engaged in other aspects of our agriculture and food systems than in protection of our agricultural resource base and natural environment.

Further Resources

National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition

This 100-member coalition offers the latest information on most federal conservation policy.

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)

Your phone book should list your local county NRCS office in the “blue” federal government sections. If not, call the state office to get the phone number of your local office

NRCS has an excellent Internet-based information system. The national NRCS website links to all state NRCS websites. In turn, state websites link to local NRCS office websites, if the local office maintains a site. Starting at the national NRCS site is the best way to begin a search of all the programs and services NRCS provides.

Federal Resources for Sustainable Farming and Ranching

By Jeff Schahczenski, NCAT Agriculture Specialist

Published November 2020

© NCAT

IP294

Slot 290

Version 112420

This publication is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. ATTRA.NCAT.ORG.