Introduction to Forest Garden Planning, Design, and Maintenance

By Katherine Favor, NCAT Agriculture Specialist,

Hannah Hemmelgarn, Center for Agroforestry, University of Missouri, and

Kelsi Stubblefield, Center for Agroforestry, University of Missouri

Abstract

Thoughtfully designed agroforestry practices contribute to environmental and economic resilience on farms and ranches. These outcomes can can be achieved at a smaller scale by planting forest gardens, also known as food forests, as multi-strata productive growing spaces. Forest gardens can be incorporated into yards, parks, roadsides, or other shared or underutilized spaces suitable for cultivation, allowing growers to maximize space, increase and diversify yields, and create opportunities for social connections and education.

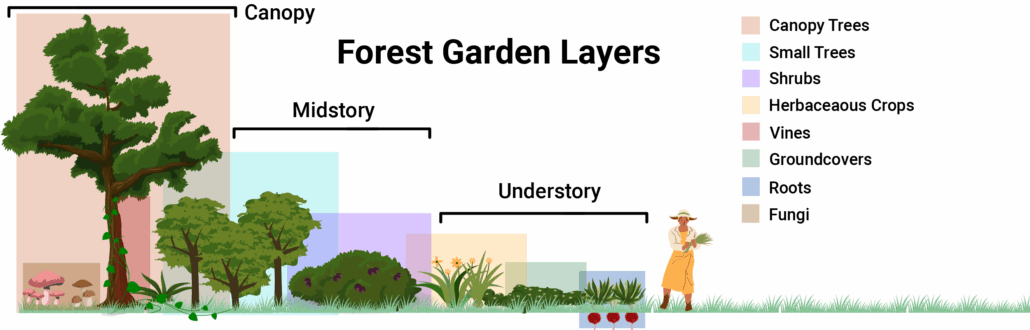

Designed like a forest edge or successional transition, forest gardens can contain multiple strata or layers that utilize energy, nutrients, and space in complementary ways both above and below ground. Image: Kelsi Stubblefield and Hannah Hemmelgarn

Contents

Introduction

Planning a Forest Garden

Ecological Design

Installing and Maintaining a Forest Garden

Conclusion: Inspiration to Action

References

Further Resources

Forest Garden Examples

Introduction

Forest gardens are multifunctional perennial (woody and herbaceous) polycultures designed and managed to mimic the structure of early successional forests or forest edges, where multiple “layers” of edible, medicinal, or ornamental plants and fungi share a single unit of space. Unlike conventional rural farms, forest gardens may be planted in relatively small areas. They require careful design to accommodate the challenges and opportunities related to their high levels of diversity and unique site circumstances. We intentionally refer to them as “forest gardens” in this publication to illustrate their ability to provide more than food products and to highlight their parallels to intensively-managed garden spaces.

The practice of forest gardening has become more popular in recent years, but multi-strata perennial gardens have been part of Indigenous land stewardship and subsistence for thousands of years. Research suggests that large parts of the Amazon rainforest, the Pacific Northwest rainforest, and tropical forests around the world are in fact large-scale forest gardens, composed of intentional plantings that have sustained communities through many generations.

Today, the role of forest gardens for human and wildlife communities is no less important. They can supplement an individual’s or a family’s nutritional needs, produce a wide variety of staple crops and medicinal plants, sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, provide critical habitat for wildlife, and offer numerous other social and ecosystem services. When planted in urban areas, forest gardens can also play an important role in regulating microclimates, mitigating the heat island effect, buffering unpleasant odors, beautifying the built environment, and facilitating community connections.

The long-term success of forest gardens will depend upon planning and design that takes into account not only the unique growing conditions of a site, but also the social dimensions and needs of those who will interact with the space. A fruitful forest garden design will consider both the complex ecological structure of the space, and also the social structure of decision-making, management, and human interactions. This guide is intended as an introduction to the planning process in conjunction with other resources referenced at the end of the document.

Disclaimer: please note that this guide is intended as a primer and is not site-specific nor comprehensive. Refer to the resources listed at the end of this publication for extended information on forest garden planning, design, and management.

Planning a Forest Garden

Forest gardens often include spaces for community connection, such as sitting areas and walking paths. Pictured here is a bench under the midstory canopy of a fig tree with comfrey growing in the understory at the Lawrence Community Orchard in Lawrence, Kansas.

Forest garden scale and function will vary depending on physical, social, and ecological circumstances, but the process for planning your forest garden can be guided by these basic steps. They can be designed for subsistence, commercial production, education, or recreation; planning decisions will be affected by the unique attributes of the site and the participating community. Start by determining your goals and objectives using these prompts as an initial guide.

Social Considerations

- What is the purpose of the forest garden? Is your primary goal to produce food, to provide a space for community gathering, to serve an educational purpose, or something else?

- Who is the forest garden intended to serve? How will they be involved in the planning process?

- Who will be involved in maintaining the garden, and how much time will they be able to dedicate to taking care of the space?

- How do you envision people interacting with the space? Will it be public or private? How will you facilitate understanding and interpretation of the forest garden?

Environmental Considerations

- What is the current ecological condition of the site, and how do you envision it changing in the next 5, 10, 15, and 20 years?

- What (and how much) do you want to harvest from your site? What, if any, site changes, amendments, or remediation will be required to ensure sustainable and healthy harvests?

- What are your conservation goals? How will the opportunities and constraints of the built and/or natural environment affect and be affected by the garden?

- What level of structural and biological diversity do you aim to achieve?

- What kind of legacy do you hope to create from this effort?

Assess the growing context

Once you have identified your goals and objectives, you can assess your “growing context”, which includes the physical and biological features of the land and the ways humans will interact with the space. Consider the following factors and available tools when assessing your growing context:

- Climate: the weather conditions in your area, including season length, temperature, and rainfall.

- Topography: The shape and arrangement of physical features on the land, including elevation and slope.

- Soil structure and fertility

- Wind direction and intensity

- Sun and shade (over a day and as it changes with the seasons)

- Photone App to determine light and shade quality and quantity

- Observed wildlife, whether wanted or unwanted

- LandPKS Software

- Existing pest issues

- Existing and historical vegetation (“weedy” plants and other indicator species’ diversity and abundance)

- Noise, odor, contamination, or other “problems” in and around your site

- Built infrastructure: existing below and above ground utilities

- 811: the national “Call Before You Dig” hotline

- Community:

- Engagement: identify community groups, initiatives, and organizations that could be involved in the forest garden, if desired.

- Legal authority over the land: determine who has legal authority over the use of the land and how that may change over time. An attorney or assessor can assist with this.

- Zoning and City Ordinances: understand what activities are allowed and prohibited in your designated forest garden area.

Inventory your resources

Take stock of the resources you already have access to, as well as the resources you will need to fulfill your goals and objectives. Resources needed for implementation and management, depending on your scale and existing context, may include:

- Financial resources

- Secure access to land

- Crop insurance and/or event insurance

- Access to utilities (water, electricity, septic, trash, etc.)

- Built infrastructure (e.g., storage shed, hoop house, cold frames, etc.)

- Cold storage for produce

- Educational materials (e.g. signage, plant identification labels)

- Tools and equipment

- Organic substrates: soil, mulch, compost

- Plant materials: starts, seedlings, and seeds

- Labor, time

- Knowledge and expertise

- Certifications and licenses

- Business or organization management skills

- Community support

Municipalities often have public mulch sites, “re-stores” with gently used building supplies, and an abundance of recycled materials like cardboard that can be used for suppressing weeds. Communities can also provide resources such as volunteer labor, shared equipment, or other shared resources, including propagated plant materials and space.

Map the site with zones and sectors

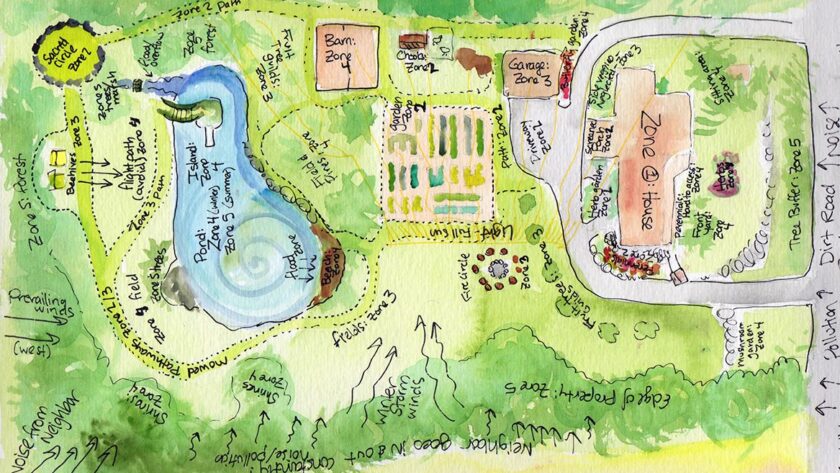

Mapping with “zones” and “sectors” is a reference to permaculture design practices that can be a helpful way to spatially assess opportunities and limitations.

Zones refer to the frequency and intensity of human interactions, from “zone 1”, an area of interaction multiple times a day, to “zone 5”, an area very rarely visited. These spatial boundaries can be fluid, but are generally related to proximity to a central hub, a home, or access points. By pairing the most management-intensive and convenience-oriented elements of your design with areas likely to be more frequented, you will achieve more energy efficient patterns of use.

Sectors describe the physical, biological, and additional “external” elements of the site. This can include sunlight and shade patterns, seasonal wind direction and intensity, precipitation and the movement (or stagnation) of water, and other attributes that require observation and attention over time. This guide includes a set of tool and resources that can help you begin to layer each of these components as part of a holistic site assessment.

These considerations are not exhaustive of the many factors that contribute to a well-designed forest garden. In the sections that follow, we will focus on the ecological components of forest garden planning and design.

Ecological Design

Species selection

Your goals, in combination with the site characteristics, available resources, and contextual limitations, will largely determine what species best fit the garden space. Many plants provide multiple types of harvests and additional benefits simultaneously. In addition to edible and medicinal plants, you may consider selecting species that provide aesthetic value to your site, serve as windbreaks, provide habitat for wildlife, attract pollinators, fix nitrogen and build healthy soil, or do all of the above. Consider your climate, USDA plant hardiness zone, land-use history, and also resident vegetation when deciding what species to plant in your forest garden. When possible, choose native and naturalized plants, or plants bred to have natural disease resilience. Another consideration when selecting species is climate change. Because forest gardens involve planting perennials that will stay in the ground for years to come, select species that are expected to do well in the face of projected temperature and weather extremes.

Example of a map drawn with zones and sectors for site planning using permaculture design. Image: Dana O’Driscoll, The Druids Garden

The layers of a forest garden

Forest gardens are designed to mimic the structure and composition of early successional forests, which are characterized by higher structural complexity (multiple “layers”), higher species diversity, and higher productivity. The “overstory” layer refers to the uppermost layer of growth. The “understory” refers to any lower layer of growth in the forest garden ecosystem. Unlike forests that have reached a more mature stage of succession, in the earliest stages, tree canopies do not dominate the site. Overstory trees and understory trees are spaced widely enough so that light can still penetrate to understory layers, which allows a wide variety of plants to thrive within multiple vertical layers. Following this pattern, forest gardens can include up to eight layers of vegetation that each inhabit a unique niche of light or shade in the space. In each layer, plants can be selected for their multiple functions: as a source of harvestable food, fodder, medicine, or ornamentals (fruit, nuts, foliage, roots, flowers etc.), to attract pollinators and other beneficial insects, to fix nitrogen or accumulate important micronutrients from deeper soil strata, and to serve as structural support and companions for other components of the garden’s plant, animal, and fungi community.

Below is a basic list of the distinct vegetation layers most common in forest gardens, though often their attributes overlap. Within each layer, examples of species selections are provided. Please note that these selections are suitable for much of the Midwestern U.S. and may not be appropriate for other regions.

- The overstory or canopy layer is the uppermost layer of foliage. It typically consists of trees that will grow to around 25 – 100 ft (7 – 30 m) in height. This layer regulates the microclimate below by providing the greatest amount of shade. Ex: black walnut, hickory, pecan, mulberry, persimmon.

- Below the canopy is an understory tree or midstory tree layer of smaller trees 7 – 25 ft tall (2 – 8 m). Ex: pawpaw, dwarf fruit trees (apples, pears, peaches, plums, cherries, etc.), hazelnut, serviceberry.

- A shrub layer consists of woody perennial bushes, shrubs, and brambles 3 – 10 ft tall (1 – 3 m). Ex: blackberry, raspberry, aronia, currant, blueberry, gooseberry, nannyberry, spicebush, witch hazel, elderberry.

- An herbaceous crop layer consists of shorter upright plants that will occupy the space below and between woody trees and shrubs, including perennial and annual plants. Both cultivated and volunteer plants can benefit the above- and below-ground living communities. Depending on the density of shade cast by the trees above, these plants need to be well-adapted to shade. Ex: sochan, comfrey, chives and wild onions, asparagus, monarda, lemon balm, yarrow, dittany, wood nettle.

- The groundcover layer consists of low-lying vegetation that can reduce weed pressure and regulate soil moisture. Plants in this layer can include sprawling herbs, mosses, or shade-tolerant low-growing cover crops, fruits and flowers. Ex: strawberries, oregano, clover, purslane, chickweed, dandelion, wild ginger, violets.

- A vine layer of climbing plants can inhabit the vertical infrastructure provided by trees, shrubs, and other strong-stemmed plants, so long as these climbers do not damage or harm their upright host. Ex: groundnut, hardy kiwi, grapes, maypop, pole beans, peas.

- A root crop layer is intended to fill an underground niche where space allows, including both perennial and herbaceous tubers and taproots. In many cases, these plants, like those in other strata of the garden, can inhabit multiple layers at once. Ex: wild leeks, ginseng, goldenseal, perennial onions, sunchoke.

- Finally, a fungi layer can be included as an additional harvest from mulch under the shade of multiple layers of vegetation, or incorporated as log-grown culinary mushrooms in shaded spaces with easy access for harvest. Ex: winecap, oyster, shiitake, maitake, blewit, and others.

Educational sign in front of blackberry trellis at a forest garden site in Columbia, Mo. The native plants selected for this site require lower maintenance while yielding an abundance of fruit and wildlife habitat.

When making your selections, consider incorporating native species as much as possible. Native plants are adapted to local conditions and are more likely to thrive in the local environment with fewer inputs. These plants also provide food and habitat for local wildlife such as birds, butterflies, and other insects, promote biodiversity and contribute to resilient and diverse landscapes. In urban areas, where habitat tends to be more limited, this food and shelter is particularly important. Native plants also support populations of natural insect predators, which contributes to integrated pest management and reduces the need for pesticides.

In many states, publicly funded native plant nurseries supply low-cost bare root saplings. Consult with local Extension staff, horticulture and conservation groups to identify nearby reliable nurseries and other sources of needed plant materials.

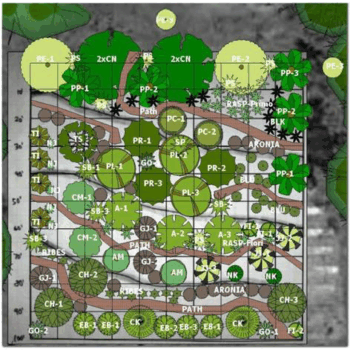

Spacing and arrangement

Because forest gardens contain multiple layers of vegetation in one unit of space, competition for light, water, and nutrients will occur between species in addition to their potential complementarity and companionship. Careful consideration of spacing will reduce competition and ensure the health of the entire system, allowing all layers of vegetation to thrive. Plant trees and shrubs far enough apart to allow sufficient light to reach the plants below. General guidelines for spacing woody species in a forest garden are as follows:

- Look up spacing recommendations for each tree species you intend to include; these are typically based on the expected mature canopy diameter of the tree and the space needed to reduce pest and disease pressure. Local Extension professionals and their horticultural guides can be a great starting place for this information. Consider adding 30-50% to the recommended spacing to ensure that tree canopies will not dominate the overstory as they mature. This can be used as a minimum spacing guideline to determine the number of overstory trees your space can accommodate.

- In spaces where management and equipment will operate best in rows, trees may be planted in a grid-like arrangement, or planted in rows that roughly follow the topography of the land in what is called a “keyline” design. This arrangement encourages the retention and redistribution of water along planted rows perpendicular to the lowest valley.

- No matter how trees are arranged, it is important to organize plants into groupings that will be complementary to each other spatially and biologically. Make note of the estimated mature plant size and root habits to minimize long-term competition above and below ground.

- Consider the space needed for harvest and care. Where garden users are willing to navigate more complex plantings, spacing can be more condensed, but if the garden is intended for educational purposes or large groups of people, sufficient paths and interpretive signage will be necessary.

- Add understory shrubs, herbaceous plants, and additional layers between and below the canopy trees with consideration to the long-term changes in light/shade and accessible space. As understory plants propagate themselves (by seed or rhizome), they will self-select over time toward the individuals and spaces best suited to your growing context, which will result in an increasingly productive and resilient system.

- Remember that any initial plantings may be removed or thinned as the forest garden grows. Ultimately, aim to have every square foot of soil eventually covered with vegetation for maximum production and ecological benefit. A denser initial planting will reduce competition with unwanted volunteer plants while light is less limiting, and can encourage a healthy soil microbiome. Nitrogen-fixing or nutrient-accumulating plants can be particularly helpful to include at the start to support soil health while trees are becoming established.

These basic guidelines are a starting place for designing your planting layout, but close observation and interaction with the space will allow you to modify your design over time. Refer to your community for input about accessibility and safety.

Grouping with guilds

Shade-tolerant varieties of strawberries at a forest garden site in Columbia, Mo, managed by the Columbia Center for Urban Agriculture.

Light, water, and nutrients are three critical resources that plants need to thrive. Given the multi-layer structure and diversity of forest gardens, it is important to remember that competition will occur between species for these resources. By grouping plants together intentionally, competitive interactions between species can be reduced and synergistic interactions between species can be increased. Intentional groupings of plants designed to maximize beneficial interactions are called “guilds.” To reduce competition, think about selecting species that occupy different niches both above- and below-ground. To increase synergistic interactions, think about the complex benefits of each plant (i.e. pollinator habitat, nitrogen fixation, physical support structures such as tall trunks, shelter from wind, protection from heat, leaf litter, nutrient cycling, chemicals that repel certain pests, etc.) and group plants together so that they can benefit from one another.

- Reducing competition for light: lower forest garden layers (the herbaceous crop layer, groundcover layer, vine layer, and root layer) will be shaded by overstory trees and shrubs. Therefore, shade-tolerant species should be selected for lower forest garden layers. Alternatively, overstory trees can be spaced to allow light to penetrate to the understory, or tree species with more open canopies can be selected so that more light reaches understory layers. Pruning overstory trees not only benefits tree health, but also increases the amount of light allowed through their canopy.

- Reducing competition for water and nutrients: trees and shrubs with large root systems should be planted at sufficient distances from other trees and shrubs in order to avoid below-ground competition for water and nutrients. Combine larger overstory trees and shrubs with plants that have more shallow root systems (some herbaceous crops, groundcovers, vines) in order to avoid competition for below-ground resources. By the same principle, plants have unique nutrient needs, so a “heavy-feeder” like melons or asparagus could be paired with a nitrogen-fixer legume like clover or peas. In general, by following companion planting guidelines, you can select species that spatially and biologically complement each other, rather than competing.

When possible, plant species combinations that provide mutual benefits and promote the overall health of the forest garden system. For example, some plant species require pollination but do not innately attract pollinators themselves, and they may benefit from neighboring plant species that attract pollinators. Some plants, such as onions and the aromatic herb basil, drive pests away from companion crops. Structurally, consider how plants will grow and take up space over time. Eventually, it may be necessary to thin overstory and understory trees to ensure that lower layers receive sufficient light. Alternatively, you may choose to replace sun-loving herbaceous plants with those that thrive in shade.

Installing and Maintaining a Forest Garden

Forest gardens are inherently complex, and they often occupy small spaces. Because of this, they can be difficult to mechanize, often relying on hand-labor or small specialized equipment. Management tasks such as soil preparation, seeding, pest and weed management, pruning, thinning, and harvesting will look different in forest gardens than on larger production farms. Attentive establishment measures and preventative maintenance are always preferable to reactive measures, but you can expect management in a forest garden to be relatively intensive.

Spacing and arrangement

When establishing a forest garden in damaged or degraded soils, it is common to plant “nurse” species first, sometimes in the years prior to planting other trees and crops, in order to increase soil fertility by fixing atmospheric nitrogen into soluble nitrogen in the soil. Nurse species are typically hardy, fast-growing native or naturalized species that are adapted to the local environment, and thrive with fewer water and nutrient inputs. They can also quickly increase soil organic matter by producing large amounts of above- and below-ground biomass, including branches, leaf litter, mulch, and root slough. When nurse plants begin to compete with other important forest garden crops, they can be coppiced or removed, as they’ve done their job of preparing the site for healthy longer-lived trees.

Before planting, be sure that the growing medium (soil, mulch, compost) will support what you intend to grow. Nurse plants, cover crops, and existing vegetation can serve to self-correct nutrient imbalances over time, but additional and ongoing amendments may be required for permanent plantings. Test your soil’s pH and available nutrients and amend the site with compost, manure, mulch, organic fertilizers, or topsoil as needed. Imported materials always carry the risk of introducing unknown contaminants to your site, so bring in materials only from trusted sources, and source locally as much as possible.

Remove unwanted biomass and prepare the planting site for establishment. When transferring any species from a container, if the roots have become pot-bound, loosen them manually. The root collar of any woody plant should be just at ground level with space on all sides for backfill soil and compost. Ensure that the soil surrounding the newly established plant allows for roots to penetrate without any air gaps; to do this, step gently around the base of the planted tree to compress these gaps without compacting. Once planted, monitor the health of transplants during this time of stress and transition. Mulch, irrigation, and protection from hungry critters (e.g. tree tubes) is critical in the early years of establishment.

Water considerations

A newly established forest garden at a public park in Columbia, Mo. Flags indicate planned companion plantings. Cages protect young trees, and the site is hand watered until irrigation is installed.

As you plan your forest garden, seasonal precipitation and the movement of water should be mapped as a sector. Consider at the outset of your design process where water is coming from (e.g., large impervious surfaces collecting and directing runoff) and where you need it to go. The management of water can have major implications in your design.

The movement of water on a site is affected by its sources, by soil qualities, and by the topography or slope and elevation. Earthworks can be applied to a site to modify the shape of the landscape and therefore the movement of water. Swales, berms, terraces, and ponds are all examples of earthworks that can be used to slow the flow of water and capture it where desired, reducing the need for irrigation in a forest garden. Perennial plantings can both benefit and be benefitted by this type of earthwork; trees planted on berms can help stabilize moved earth and the berms can serve as a space with increased drainage adjacent to higher concentrations of water in the nearby swales.

In most of the US, some irrigation or hand watering will be necessary to establish and maintain a thriving forest garden. Where rainfall is regular, irrigation might only be needed during establishment, or to supplement rainfall during dry months. As weather patterns become less predictable, resilience to both droughts and floods will be important in your structural design and plant selections. Forest gardens are naturally well adapted to catching and storing rainfall in soil and plants, but additional measures can be taken to further prepare for variable precipitation, including the installation of rain barrels and rain gardens, or, for dry conditions, applying xeriscaping, mulching, and efficient drip irrigation systems.

Because of their structure, many forest gardens can be susceptible to mold issues such as powdery mildew, and excessive moisture can exacerbate this problem. Spacing and design that allows for air flow will reduce this risk, along with avoiding overhead irrigation, which can create moist conditions on plant leaves.

Reducing weed pressure

Unwanted plants can present a challenge in forest gardens, as with any agricultural system. Many of the plants typically considered “weeds” in annual gardens actually play important roles in remediating soil and can provide an abundance of food and medicine. However, the presence and movement of invasive plants can have serious negative consequences. Where time and labor allow, removal of above and below ground invasive plant biomass is an important first step. Seed banks in the soil may persist, however, and the following options for organic weed management can support long-term control:

- Occultation, in which dark plastic tarps or landscape fabric is laid down over weeds for 6-8 months.

- Solarization and biosolarization, in which clear plastic is sealed over weeds for two weeks to one month.

- Tillage, in which weed roots and rhizomes are broken up and killed. In small spaces, this can be done with hand tools.

- Mulch and compost, which block sunlight from reaching weeds. Mulch can be obtained for free from tree trimming services in many urban areas.

- Sheet mulching in which cardboard and mulch are layered on top of one another to prevent light from reaching weeds.

- Mowing with lawn mowers, weed wackers, and other small equipment.

- Grazing animals such as chickens, sheep, pigs, if allowed by local ordinances.

- Cover cropping with groundcover that smothers and replaces weeds. In forest gardens, edible cover crops such as winter peas, oregano, mint, etc. can be used both as weed control and for harvest.

Pest and disease management

As with any agricultural system, pests, wildlife, and pathogens exist in a forest garden. Integrated pest management (IPM) principles and preventative measures can facilitate organic pest and disease control. Preventative tactics involve annual pruning, avoiding overhead irrigation to reduce the likelihood of mold, planting native and flowering plants to attract beneficial insects, maintaining high levels of plant diversity, frequent sanitizing of tools, and monitoring for early detection of a pest or disease. If an infestation or outbreak does occur, consider attracting beneficial insects, using traps or trap crops, and using organic alternatives such as diatomaceous earth or dormant oil sprays (for insects), hot pepper spray (for other wildlife), or copper sprays (for fungi, bacteria).

Always consult a trained specialist before taking measures that may affect any forest garden inhabitants. University Extension horticulture specialists and USDA technical staff will be able to direct you to resources specific to your needs and circumstances.

Conclusion: Inspiration to Action

Forest gardens can be incorporated into any number of open spaces: backyards, neighborhood parks, schoolyards, spiritual gathering places, small farms, or underutilized lots. Because of their diversity both socially and ecologically, there is no definitive blueprint or design for forest gardening. Opportunities and limitations presented by the environment and its inhabitants often define a forest garden’s structure and purpose.

Consider, for instance, land ownership. Whether rural or urban, legal authority over the land may change over time. If the longevity of the forest garden and the long-lived perennial plants established there is of concern, a land trust or long-term lease arrangement can help ensure that goal. Agrarian Land Trust is a prime example of community trusts rooted in land stewardship (agrariantrust.org). For long-term lease guidance, check out the Savanna Institute’s downloadable Long-term Lease Workbook and case studies (savannainstitute.org/resources). Also consider the history of land-use in your area; what natural plant communities will the soil and climate support? How might a changing climate affect the composition of that community? As much as possible, when steps can be taken to proactively anticipate needed changes (from the beginning and throughout the life of the forest garden), these enduring spaces will be more likely to thrive. Ultimately, each of these decisions will contribute to the legacy that grows from these efforts, as perennial harvests and as insights about what is possible when deep roots are nurtured.

The benefits of forest gardens have been documented around the world, from food production that contributes to critical supplies of fresh fruits and vegetables, to mental health and well being for those who interact with the sites, and education that combats “plant blindness”. The designs, species, and benefits of forest garden spaces are diverse and plentiful, contributing to the health of ecosystems and communities in innumerable ways.

References

Introduction

Armstrong C.G., Earnshaw J., McAlvay A.C. (2022). Coupled archaeological and ecological analyses reveal ancient cultivation and land use in Nuchatlaht (Nuu-chah-nulth) territories, Pacific Northwest. Journal of Archaeological Science 143: 105611

Favor, K., Hemmelgarn, H., and Stubblefield, K. (2023). Urban Agroforestry. Technical Guide.

Kumar, B. M. and Nair, P.K. (2004). The enigma of tropical homegardens. Agroforestry Systems 61(1): 135-152.

Lovell, S.T.; Hayman, J.; Hemmelgarn, H.; Hunter, A.A.; Taylor, J.R. (2021). Community Orchards for Food Sovereignty, Human Health, and Climate Resilience: Indigenous Roots and Contemporary Applications. Forests 2021, 12, 1533.

Shi, X. (2022). The urban food forest: Creating a public edible landscape. Urban Design International.

Planning a Forest Garden

Hemenway, T. (2001). Gaia’s Garden: A Guide to Home-Scale Permaculture. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, LLC.

Millison, A. (2019). Introduction to Permaculture: Zones. Oregon State University.

Ecological Design

Crawford, R. (2010). Creating a Forest Garden: Working with Nature to Grow Edible Crops. Greenbooks, Totnes, Devon, United Kingdom.

Yeomans, P.A. (1993). Water for Every Farm: Yeomans Keyline Plan. Queensland, Australia: Keyline Designs.

Conclusion

Clark, K. H., & Nicholas, K. A. (2013). Introducing urban food forestry: A multifunctional approach to increase food security and provide ecosystem services. Landscape Ecology, 28.

Dwyer, J.F., McPherson, E.G., Schroeder, H.W., Rowntree, R.A. (1992). Assessing the benefits and costs of the urban forest [PDF]. Journal of Arboriculture 18(5): Sept. 1992.

Park, H., Kramer, M., Rhemtulla, J. M., & Konijnendijk, C. C. (2019). Urban food systems that involve trees in Northern America and Europe: A scoping review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 45, 1-9.

Peloso, J. (2007). Environmental Justice Education: Empowering Students to Become Environmental Citizens. Penn GSE Perspectives on Urban Education, 5(1).

Poe, M. R., McLain, R. J., Emery, M., and Hurley, P. T. (2013). Urban Forest Justice and the Rights to Wild Foods, Medicines, and Materials in the City. Human Ecology, 41(3), 409-422.

Riolo, F. (2019). The social and environmental value of public urban food forests: The case study of the Picasso Food Forest in Parma, Italy. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 45, 1-12.

Romanova O., Lovell S.T. (2021). Food safety considerations of urban agroforestry systems grown in contaminated environments. Urban Agriculture and Regional Food Systesms.

Further Resources

Community Food Forests. An interactive map and case studies of community food forest initiatives across the United States.

The Community Food Forest Handbook (2018) by Catherine Bukowski and John Munsell. Chelsea Green Publishing, LLC. A book about the civic aspects of community food forests, with ideas for building and sustaining momentum, working with diverse stakeholders, integrating assorted civic interests and visions within a project, creating safe and attractive sites, navigating community policies, and more.

Creating a Forest Garden—Working with Nature to Grow Edible Crops (2010) by Martin Crawford. Green Books, UK. Information on forest gardens, including planning, design, planting, and maintenance, as well as a detailed directory of more than 500 edible plants.

Edible Forest Gardens, Vol. 1 (2005) by Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier. Chelsea Green Publishing, LLC. Introduces historic and visionary bases of edible forest gardens. It describes ecological relationships, structures, and succession.

Edible Forest Gardens, Vol. II (2005) by Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier. Chelsea Green Publishing, LLC. Details the design process, site preparation and establishment, and maintenance of the edible forest garden.

Forest Gardening: Cultivating an Edible Landscape, 2nd Edition (1996) by Robert Hart. Chelsea Green Publishing, LLC. Describes how to transform even a small cottage garden into a hospitable diverse habitat for songbirds, butterflies, and other wildlife by using a wide variety of useful plants.

Perennial Pathways: Planting Tree Crops: Designing & Installing Farm-Scale Edible Agroforestry. Savanna Institute. Champaign, IL. A comprehensive guidebook to designing and installing farm-scale edible agroforestry.

Urban Agroforestry (2023) by Katherine Favor, Hannah Hemmelgarn, and Kelsi Stubblefield. National Center for Appropriate Technology. Created by the authors of this publication, the NCAT guide explores applications of agroforestry systems in urban environments, which often incorporate elements of forest gardens.

USDA NRCS PLANTS Database. An extensive plant database to determine species for agroforestry operations based on different criteria. plants.usda.gov

Forest Garden Examples

Here we provide a few examples of thriving forest gardens in our region as a source of inspiration. In all cases, these sites and the way people interact with them has and will continue to change over time as the structure and composition of perennialized gardens necessarily shifts as they mature. Please note: all language in this section is pulled directly from the organizations’ websites.

EarthDance Organic Farm School – Ferguson, Missouri EarthDance is a teaching farm, sharing the craft and science of organic farming with people from all walks of life. Through the Organic Farm School programs, EarthDance cultivates food leaders alongside abundant fresh produce. [Their] 250-tree mixed orchard features varieties of pears, apples, cherries, pawpaws and more, planted on water-harvesting berms and swales.

The Giving Grove Community Orchards – Various locations The Giving Grove supports neighborhood volunteers in planting and caring for fruit trees, nut trees, and berry brambles that improve the urban environment, increase tree canopy and provide a sustainable source of free, organically-grown food for neighborhoods facing high rates of food insecurity. [Their] network has more than 400 orchards across the U.S. with the potential to grow nearly 3 million servings of free, fresh food annually while re-invigorating urban green spaces.

Principia Permaculture Orchard – St. Louis, Missouri Working closely with high school science teachers, Custom Foodscaping helped turn [a local school’s] grassy hillside into an explosion of edible plants and native flowers. To manage water on this sloping landscape, contour berms and swales were used to slow water and sink it into the ground. A food forest was planted on the berms with a tremendous diversity of native flowers, herbs, and fruit trees, all of which produce in the spring and fall while students are in school. Students K-12 can now utilize the permaculture orchard to make herbal tea, study native pollinators, hold class under the pergola, and harvest loads of fruit.

Columbia Center for Urban Agriculture’s Agriculture Park – Columbia, Missouri One part forest and one part fruit orchard, the [CCUA] Food Forest is an area of Columbia’s Agriculture Park with 40+ individual fruit and nut trees that grow well in mid-Missouri’s climate. Similar to the understory of a forest, beneath and around the fruit trees are different perennial shrubs, berry brambles, and herbs, all of which provide sources of food from forest floor to canopy. [Visitors can] wander the gravel pathway to find apple, cherry, peach, apricot, pear, plum, and pecan trees, plus possibly some less-familiar fruits such as che (Chinese Mulberry), jujubes, Asian persimmons, and medlars.

The canopy and shrub layers of Cultivate KC’s food forest (February 2012). Image: Cultivate KC

Cultivate KC Food Forest – Merriam, Kansas Cultivate KC is a locally-grown non-profit working to grow food, farms, and community in support of an equitable, sustainable and healthy local food system for all. [One of their sites is] a small 1/4-acre lot in Merriam, Kansas, planted in 2011 with support from a National Audubon Society and Toyota grant, that is home to 39 varieties of fruit and nut trees and 12 different shrubs.

Introduction to Forest Garden Planning, Design, and Maintenance

By Katherine Favor, NCAT Agriculture Specialist,

Hannah Hemmelgarn, Center for Agroforestry, University of Missouri, and

Kelsi Stubblefield, Center for Agroforestry, University of Missouri

©NCAT, May 2025

IP669

This work was also funded through the University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry under cooperative agreements 58-62275-029, 58-6227-2-008, and 58-6227-5-028 with the USDA Agricultural Research Service.