The Impact of Grazing Frequency and Recovery Period on Plant Diversity and Soil Health

Print This Post

Print This Post

By Justin Morris, Regenerative Livestock Specialist

During my extensive travels working in pastoral ecosystems for nearly 20 years, ranging from Hawaii to New Hampshire and a lot of places in between, I’ve observed a common phenomenon. Whenever I would see a pasture that was always grazed down very short, I would see maybe two or three species of plants there. At the opposite end of the spectrum, I observed fields where livestock were never permitted to go and again, I would see a few plant species at best. Between these two extremes I found pastures with incredible diversity. So, what was driving plant diversity or the lack of it?

Kentucky Bluegrass (Poa pratensis). Photo: University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food and Environment

Orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata). Photo: University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food and Environment

Diversity of plants is a key indicator of healthy pasture and healthy soil. Diversity buffers a landscape from extreme weather events and climatic changes because each plant species has different growing requirements than another plant species growing nearby. This makes it possible that, no matter whether it’s dry, wet, hot, or cold, there’s always a plant that can thrive — even if it’s a plant we don’t necessarily want. This same pattern holds true regarding how frequently and severely a plant can be grazed and still survive.

In a pasture with several different plant species, some plants recover more quickly from increasing grazing pressure than others. Increased grazing pressure usually comes in the form of livestock remaining in the same field and re-grazing the same plants as soon as a little bit of growth takes place. Increased grazing pressure can also happen if livestock leave a field but then return to the same field before previously grazed plants have recovered. In both situations, livestock returning to graze plants that have not fully recovered favor plants that need only a short recovery period. These plants generally have shallower roots, don’t grow as tall, and carry their growing points very low. Examples include plants such as Kentucky Bluegrass (see photo at left) and White Clover. This contrasts with plants at the other end of the spectrum that need a longer recovery period and are better adapted to survive under less frequent grazing. These plants generally have deeper roots, are taller, and carry their growing points higher. Examples of these plants include Orchardgrass (see photo at right), Meadow Brome, Tall Fescue, Reed Canarygrass, Big Bluestem, and Timothy.

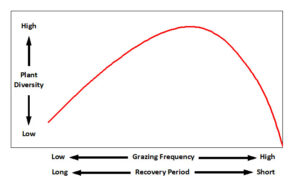

Relationship between grazing frequency and plant diversity.

The graph at right shows that plant diversity is maximized with moderate grazing frequencies and recovery periods. This is because plants that thrive under low and high grazing frequencies can exist in the same pasture at the same time. Plant diversity decreases at: 1) low grazing frequencies because of competition between plants for the same resources; and 2) high grazing frequencies because only plants that require a short recovery period can regrow quickly after being re-grazed.

Because grazing frequency and recovery period have such a large impact on plant diversity, they also have a significant impact on soil health. Research has shown that when plant diversity in grasslands increases, soil aggregation, one of the most important indicators of soil health, also improves. As soil aggregation improves, other aspects of soil and plant health are enhanced, which can include:

- Increased soil pore space

- Increased water infiltration

- Increased plant and soil microbial available water

- Increased gas exchange to allow air in and carbon dioxide out

- Increased rate of photosynthesis

- Increased plant growth

- Increased abundance and diversity of soil life

- Increased nutrient availability for plants

In pastures where short, sod-forming grasses predominate, plant diversity can be increased gradually through less frequent grazing and longer recovery periods. This allows plants that need a much longer recovery period to eventually come back into the system, often without the need to plant anything. For pastures where thatch is building up or where perennial grass old growth is preventing new growth from taking place or where woody plant species are encroaching, plant diversity can be increased by grazing more frequently and shorter recovery periods.

Related Resources:

Livestock and Pasture Management

Pasture, Rangeland, and Adaptive Grazing

Why Intensive Grazing on Irrigated Pastures?

This blog is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. ATTRA.NCAT.ORG.

NCAT

NCAT