Overgrazing and the Maturing of an Adaptive Grazing Thought Process

Print This Post

Print This Post

By Dave Scott, NCAT Livestock Specialist

The Problem

Close to 20 years ago, we noticed a discouraging event slowly unfolding on our pivot-irrigated pasture of 12 acres: The first 120 feet of the pasture starting from the pivot point was producing less and less grass in comparison to the remaining perimeter of the pivot.

How come?

We were moving every day to prevent overgrazing. Daily moves cure everything, right?

Was the scourge of the Intermountain West, quack grass, creeping in? No, I took a spade and looked for the characteristic root stolons. None there.

Okay then, maybe the used pivot we bought a few years before was not outfitted with the right sprinkler package, causing uneven irrigation. Of course! A few rain gauges placed in the field told us that was not the answer, however.

We reasoned then that it had to be that the grass stand was just getting old. It was conventional wisdom, was it not, that stands just petered out and needed rejuvenation.

So, we plowed up the field and reseeded.

A few years later, we had the same problem. So much for conventional wisdom.

By this time, I had learned something about soil health and infiltration tests. Check out how to do one here.

Infiltration tests are a simple way to measure soil health right on the farm. The faster water infiltrates, the more soil aggregation, or clumping of soil particles, there is—and more air space between the aggregations. Soil aggregates are microbial housing units: In them, microbes live and exchange plant nutrients for plant root exudates (microbial food). An abundance of aggregates such that the soil looks like dark cottage cheese is an indicator of robust microbial biology.

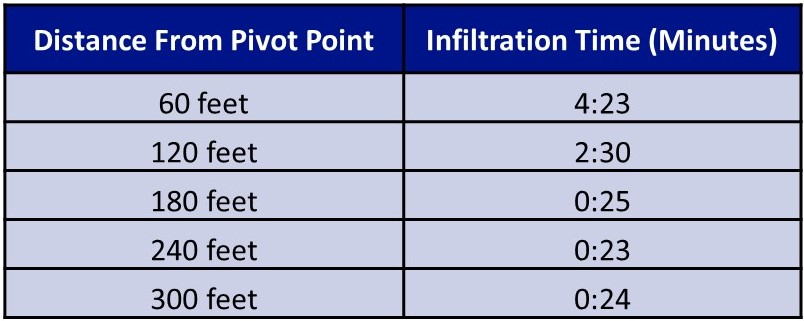

Maybe our problem had something to do with the soil microbial populations in that stretch of the pasture! So, I measured the infiltration rate of one inch of water every 60 feet on a transect out to the outer edge of the pivot. Here is what I found:

Oh, my goodness, if that does not hit you over the head, what could?

I looked again at the grazing habits of the sheep. Yes, they were grazing down to two to four inches the first 120 feet from the pivot point, even though we were moving daily. And, the outside perimeter had a nice 10- to 12-inch residual of trampled grass (see photos). With this observation, I then looked to see if the stunted grass had fully recovered when we entered into one of those paddocks (see Intensive Grazing: One Farm’s Set Up, Ch 2). Eureka! The light bulb finally went on! That grass was definitely not fully recovered.

View at 120 feet from pivot point.

View at 240 to 300 feet from pivot point.

I had finally found my answer: I was grazing non-recovered grass. Ooops.

So, what was going on?

With a stock water source in the center, we had divided our pivot into 10 pie-shaped paddocks, each about 0.7 acres in size and had grazed 500 ewes and lambs on them for 24 hours, unwaveringly, for nearly 20 years.

For all those years, we were overgrazing. Not the whole paddock, but this small part of it. Overgrazing is a downward spiral of events: Unrecovered plants never getting a chance to feed soil microbes, creating slow foliage and root re-growth, creating unrecovered grass, creating starving microbes… and on and on.

Why had it taken me so long to tumble? You tell me, but please be kind.

The Remedy

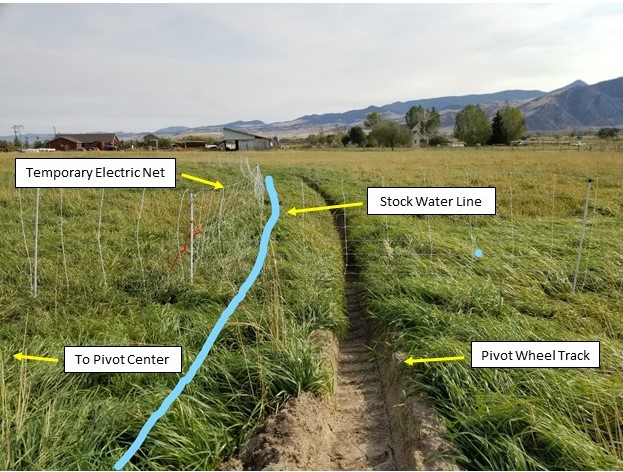

It was easy. Just run a black poly water line around the pivot wheel track, dividing the pasture into a small circular core and an outside donut. Set a temporary net on top of the pipeline and now you can create six nicely shaped, square paddocks in the donut and four smaller, but evenly sized, paddocks in the center core. All temporary, of course. Voila! Instead of 10 pies, we now have 10 squares.

And grazing control.

The Moral

Overgrazing is solely a matter of an uncontrolled livestock grazing behavior—and it definitely has a measurable effect on soil health. Sharpening the adaptive grazing thought process takes time. Maybe, as in my case, it takes longer for some than others. I hope that this can help you with your regenerative grazing and your adaptive aptitude!

Related Resources

Pasture, Rangeland, and Grazing Management

Irrigated Pastures: Setting Up an Intensive Grazing System That Works

Why Intensive Grazing on Irrigated Pastures?

Multi-species Grazing: A Primer on Diversity

Episode 63. Regenerative Grazing: Outcomes and Obstacles

All photos by Dave Scott.

This blog is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. ATTRA.NCAT.ORG.

NCAT

NCAT

USDA NRCS photo by Carly Whitmore

USDA NRCS photo by Carly Whitmore

USDA photo by Lance Cheung

USDA photo by Lance Cheung