Mastering Smoke and Serenity: Tips for Beginning Beekeepers

Print This Post

Print This Post

By Eric Fuchs-Stengel, NCAT Agriculture Specialist

Back in the olden times, hardscrabble beekeepers worked their hives in the hot sun with no suits or gloves. They would puff on cigars, blowing smoke up around their faces, filling the air underneath their wide-brimmed bee veils. This smoke would keep bees, either defensive or curious, away from their upturned mustaches, long beards, and sunbaked faces. Meanwhile, these old-timers would work methodically, gently squeezing the bellows of their copper smokers, floating a thick gray smoke, often a mix of burning pine needles and wood chips, into their Langstroth beehives.

Two beekeepers applying smoke to a Langstroth hive. Photo: Eric Fuchs-Stengel

The smoke served (and continues to serve) many functions: it distracts the bees, confuses their olfaction system (smell and pheromone communication), and signifies the potential of an incoming forest fire. The simple practice of using a smoker goes all the way back to ancient times and is still a cornerstone of modern-day beekeeping. Modern beekeepers may have lost the cigars and the outlandish facial hair, but the smoker remains in both copper, stainless steel, and aluminum forms and is a symbol of sustainable, productive, and successful beekeeping.

When I was a brand-new beekeeper, my local bee club partnered with a remarkable bee mentor who rarely used a bee smoker. She was extraordinarily successful with her hives, stewarding many through Varroa mite infestations and cold winters. She prioritized moving slowly and thoughtfully, with movements that were not jarring or alarming to bees. I have not seen this slow and steady “Tai Chi” style of beekeeping replicated anywhere else in the beekeeping world. She would on occasion use smoke, but it was rarely needed when she worked her mature, well-aged, well-mannered, and “spiritually connected,” hives in her home apiary. On a beautiful, sunny, summer day, I would watch my mentor slowly opening, inspecting, and working the hives with her bare hands—no smoker lit, no fear at all, and no defensive hives stinging and buzzing her in the face. Truly, a sight to behold.

As an inexperienced beekeeper, I thought this was the way I should begin raising my bees, which brings us to our story. For several years I kept my colonies on a horse farm. My mentor would visit me and wear a bee suit with no gloves so that she could feel what was happening in the hives and to what extent she was jostling the frames around. The bees were calm and peaceful around her. She was a master of this practice. I, on the other hand, was extremely nervous. I wore a full bee suit, thick leather gloves, and sweated profusely every time I worked my hives in the sun. The smell of my stress radiated outward, and my sweat soaked into the suit, which I did not really wash. In an attempt to imitate my mentor, I did not use a smoker. I would try to be gentle. Slow. Steady. But the fully aware, undistracted-by-smoke, energetic bees would BUZZ LOUDLY and swarm around my face covered by my bee veil. This would lead to me crushing bees under my fingers with the thick leather gloves, jarring and jolting frames as I removed them from the colony.

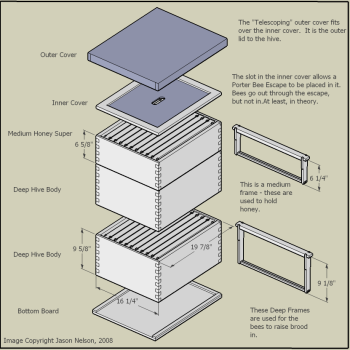

Basic anatomy of a Langstroth hive. Source: Jason Nelson, 2008.

In the heat of summer, I would struggle lifting off the heavy honey super, then the top deep, to do a full inspection on the bottom deep—as I had interpreted that to be standard practice—at least once a month. (In actuality, I was over-inspecting my colony due to my inexperience. A skilled beekeeper can read the comb in a hive to determine its health and would need to dive deep into the brood chamber much less frequently.) The bees would buzz, cluster on top of the deep frames, and bubble over the sides of the hive box like lava.

In short, my bees were angry. My leather gloves were covered in stingers. The edges of the hives were full of dead bees crushed between the deeps and supers. My suit was smelly with the stench of nervous sweat. Every time I went to the hives I was scared and worked faster to try to avoid the eruption of bees out of the colony, which only made things worse.

Toward the end of July, I found one of my hives densely packed and sealed tight with propolis, which made it difficult to open. Every time I freed the inner cover, prying it apart with my hive tool, a loud crack would sound, and the sweet smell of bananas would flow out into the air. That banana smell is the alarm pheromone released by the bees’ Koschevnikov gland, which contains isoamyl acetate (the same compound that naturally occurs in bananas). The bees would produce this pheromone upon my arrival and fan it throughout the hive. As I lifted the lid off the hive, the bees buzzed and flew into my veil aggressively, then shot out into the surrounding area, stinging farm visitors, and harassing workers.

For the seasoned beekeepers reading this, it already sounds like a nightmare scenario. But to top it all off, something else had also been occurring that I had not realized would be an issue. About fifteen feet in front of the hive was the farm’s horse-washing station. Every day, several horses would be brought out of the stalls and sprayed down, soaped up, and washed—in the flight path of the forager bees. The animal smell and dust would waft into the hive entrances, further agitating hives already on edge from my nervous management practices.

Honeybees are excellent at mapping and remembering where to find nectar. Photo: Lance Cheung, USDA

Honeybees have a great memory when it comes to smells. Their brain is tiny but contains up to one million neurons and is organized into clusters called “lobes.” Each lobe controls distinct functions or activities, and one particularly important lobe is called, the “mushroom body.” This lobe is enlarged in honeybees and takes up to 20% of their brain. Its purpose is to receive sensory information like smell and taste, learn about that information, and remember it for the future. This is what allows the bee’s brain to recall certain flowers that are good nectar sources. Likewise, they can also recall the smells of threats like horses, or a scared beekeeper like me.

As the season progressed, I started to receive calls about honeybees stinging visitors as they got out of their cars. Farm staff could be on the other side of the farm working when all a sudden a stray honeybee would fly in their face, get stuck in their hair, and sting them. My colony had become chronically on-edge, and something needed to be done. First, I tried to re-queen the colony. I bought a gentle, healthy, and highly regarded Carniolan queen from a local queen breeder and put it in the hive. This did change the hive temperament a little bit, but I still had stinging issues and excess defensiveness from the colony. When winter arrived, I decided to move the colony to a new location. It took me years to fully understand all the factors that led to turning this hive—which had initially been calm and peaceful—into the volcano of overflowing guard bees that it became. Here are some key lessons I learned:

One common model of smoker used in beekeeping to keep the hives calm. Photo: Eric Fuchs-Stengel

- Use a smoker. As a new beekeeper you can’t avoid crushing and killing bees and one of the absolute best tools to avoid prevent stress on bees is a smoker. Today, I usually light my smoker with a tiny bit of dry cardboard. Then I pile it up slowly with pine needles and woodchips. I top it off with a layer of wet mugwort weeds, green grassy material, or other green vegetative material growing around the farm. This green layer will cool the smoke as it leaves the smoker, ensuring the smoke is not so hot it would burn the bee wings or spread hot ash into the hive. I use mugwort as my first choice because the bees appear to like the smell.

- Observe your site. Scope out your potential apiary location before you place hives there. What animals live in the area? What type of weather patterns impact it? Is there a strong wind? Lots of shade? Too much sun? Will weeds impact the hive entrance?

- Be careful about smells! Wash your bee suit and gloves monthly. Try your best to visit your hives after a shower when your personal pheromones are at a minimum. Try to stay less sweaty when you work your hives by buying a ventilated bee suit and dressing lightly under it.

- Don’t stress over applying smoke at the beginning. If you want to be “Zen” with your bees, that can happen over time. Master the basics first and then you can experiment with no gloves, no suit, or no smoke.

- Use equipment that works for you: Thick leather gloves with no dexterity will kill bees if you aren’t careful. If you are feeling brave and comfortable with your hives, try thinner gloves that fit tighter to the hand or nitrile exam gloves (which the bees can sting through) so you can have dexterity without leaving skin exposed.

I hope you can benefit from the mistakes I made as a new beekeeper, so you’ll be able to start your beekeeping career off a little less painfully than I did. Please feel free to reach out to me with questions, or to let me know if there is other beekeeping information you need from us at ATTRA!

Sources:

Paoli, M. and Galizia, G. 2021. Olfactory coding in honeybees, Cell & Tissue Research 383, pp. 35–58.

Conrad, R. 2017. Natural Beekeeping, Revised and Expended ed. From Chapter 2, Working With The Hive / Attitude. Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, VT. pp. 30–31.

ATTRA Resources:

Podcast episode: Beekeeping Basics with Eric Fuchs-Stengel

Canva Pro

Canva Pro