Grazing for Resilience: Bouncing Forward from Catastrophic Events

Print This Post

Print This Post

By Justin Morris and Linda Poole, Regenerative Grazing Specialists

For many areas of the western United States and Canada, 2021 was one of the hottest and driest years in recorded history. With temperatures exceeding 110 degrees F and precipitation at one-third to one-half of what’s been the norm, these are unparalleled conditions that are catastrophic in their effect on the land, animals, and people.

Photos: Linda Poole, NCAT

But what is to be done when nature dishes out severe weather events such as flooding, fire, or grasshoppers that eat every green leaf in sight? Is it possible to not just bounce back from such catastrophes but to bounce forward by rising to even greater resilience in the future? The answer is a resounding YES!

Grazing Management for Soil Health

For graziers, one of the most important determinants in whether you bounce forward or fall back from catastrophe is grazing management. By focusing on soil health principles, graziers can greatly speed the recovery of their land.

Photos: Linda Poole, NCAT

This is accomplished by strategically controlling: 1) when livestock show up; 2) how long they stay in one area; 3) how frequently they return to the same area; and 4) the level of intensity (stock density) that occurs in each field. These four dimensions of grazing management are adaptively implemented to improve plant health. When not too much of a plant is grazed off and that happens infrequently, plant roots continue growing. Roots are conduits for delivering sugars and a host of other compounds to bacteria and fungi in exchange for nutrients. Glue-like compounds released by plant roots and soil life help the soil to aggregate so more pore space is created. As pore space increases in the soil, the soil’s capacity to infiltrate water, hold water, and cycle nutrients also increases. All these factors improve plant health and forage availability. This, in turn, improves livestock health and decreases reliance on purchased inputs like minerals and hay, which are usually very expensive.

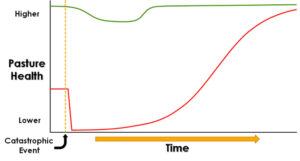

The state of health of a pasture before a catastrophe determines how the pasture responds during and after the catastrophe. In the figure above, we see two pastures at two different levels of health. The pasture with a lower state of health, represented by the red line, rapidly decreases in health when a catastrophic event happens, but then takes a long time to improve to its pre-catastrophic state. This is an example of a pasture with very low resiliency, as it cannot withstand or recover quickly from a catastrophic event. On the other hand, the healthier pasture, represented by the green line, experiences a delayed and more gradual decrease in health, and then quickly returns to its previous state of health. This is an example of high resiliency.

To decrease the time for a less healthy pasture to return to or improve beyond its pre-catastrophic state, we must adhere to soil health principles.

To decrease the time for a less healthy pasture to return to or improve beyond its pre-catastrophic state, we must adhere to soil health principles.

What do these principles look like in a grazing scenario? Here are some guidelines that incorporate these principles for improving soil health, recovering from catastrophe, and creating pastures with greater resiliency:

- Begin grazing plants in the elongation growth stage (or the reproductive growth stage, if the pasture has been decimated).

- Stop grazing plants while still in the elongation growth stage or earlier; leave 50% or more of the above-ground plant growth.

- Create enough paddocks per herd for a three-day grazing period when plants are growing quickly and a five-day grazing period when plants are growing slowly.

- Monitor pasture growth rates to adjust how fast or slow livestock move through the rotation.

- Don’t bring animals back until the pasture has fully recovered.

- If no pasture is fully recovered before the second graze, move livestock to one area and feed hay until the pasture is recovered.

- Fluctuate grazing timing, duration, frequency, and intensity (stock density).

Catastrophe or Opportunity? You Decide!

When a natural disaster strikes, it can be hard to imagine that anything good might result. But look deeply at the situation and you might find ways to use this time to pivot your operation to new levels of success. Graziers might use a catastrophe as a pivot point to improve their pastures, livestock, or business plan:

- When the established vegetation has been battered down to the roots, you can wait to see what types of plants return, or you might seed the pasture with a diverse mix of grasses and forbs that provide enhanced nutrition and greater forage availability.

- What plant species are adapted to thrive in conditions you expect in coming years?

- Wanting to shift your forage base in a better direction? Consider turning the grazing strategies above on their head if there are grass species you want to decrease in future years. For example, if you had a monoculture of crested wheatgrass or fescue prior to the catastrophe, can you fiddle with grazing in ways to hold back the dominant grass while giving other plants time to establish?

- If you destocked, consider restocking so that there are fewer, but better adapted, animals.

- Does the species, breed, and class of your livestock fit this new forage base?

- As your land recovers, can you branch out from your grazing operation into related businesses or partnerships to ease the financial strain?

Whether pivoting your pastures, livestock, or business plan, it’s essential to make sure that the land cycle and the livestock cycle are synchronized with each other.

The graphic above shows an example where the land and sheep cycles are in harmony. Peak forage production in May and June matches when the highest forage quality is required by ewes that are either lambing or in early lactation. Weaning and selling lambs in October means that forage demand is lowest when the nutritional value of the pastures is at a low ebb over the winter.

The graphic above shows an example where the land and sheep cycles are in harmony. Peak forage production in May and June matches when the highest forage quality is required by ewes that are either lambing or in early lactation. Weaning and selling lambs in October means that forage demand is lowest when the nutritional value of the pastures is at a low ebb over the winter.

Pivoting Ourselves

No discussion of bouncing forward from catastrophe would be complete without addressing how we can personally become more resilient to troubles. In his book The Resilient Farmer, New Zealand shepherd Doug Avery talks frankly about how stress from drought and two earthquakes drove him to the brink of suicide. He shares how he changed his farming operation to become more resilient, but even more importantly, Doug tells how he learned to manage his “top paddock” – his mind – to find opportunities for personal and professional growth and satisfaction in the aftermath of disaster:

“I thought the problem was drought, it wasn’t. My problem was the way I farmed and the way I thought about things. . .. If we grab a helping hand, that’s when change becomes possible. . .. Without hope, nothing else follows.”

Doug Avery’s message is that no matter what catastrophe we’re facing, the way forward is to reach out to others for help rather than trying to deal with it on our own. We are much stronger together than we are individually.

In the end, surmounting catastrophe is about nurturing beneficial connections between all living beings in our grazing operations: the livestock, the land, the soil life, ourselves, and our communities. With the resilience created through a web of strong, reciprocal relationships, we create a brighter, more prosperous future for all.

For more information on this topic, see the January 2022 Food Animal Concerns Trust (FACT) webinar featuring NCAT Regenerative Grazing Specialists Justin Morris and Linda Poole and this related resource list.

Related ATTRA Resources:

Grazing Management for Drought

Regenerative Grazing Compendium

Programs Focus on Farmer Well-Being

ATTRA Livestock Webinar Series: Building Strong Foundations

Part 1 Taking Care of Your Land

Part 2 How Many Animals Should I Have?

Part 3 Choosing Livestock for Your Farm

Other Resources:

Creating Locally Adapted Herbivores with Dr. Fred Provenza

Pasture Management for Limited Resource Farmers

Regenerating Soils with Adaptive, High-Stock Density Grazing

Livestock Compass: A Profit Management Tool for Producers

This blog is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. ATTRA.NCAT.ORG.

Jean Ogdon/ Creative Commons

Jean Ogdon/ Creative Commons

NCAT

NCAT