Small-Scale Livestock Production

By Margo Hale, Linda Coffey, Terrell Spencer, and Andy Pressman, NCAT Agriculture Specialists

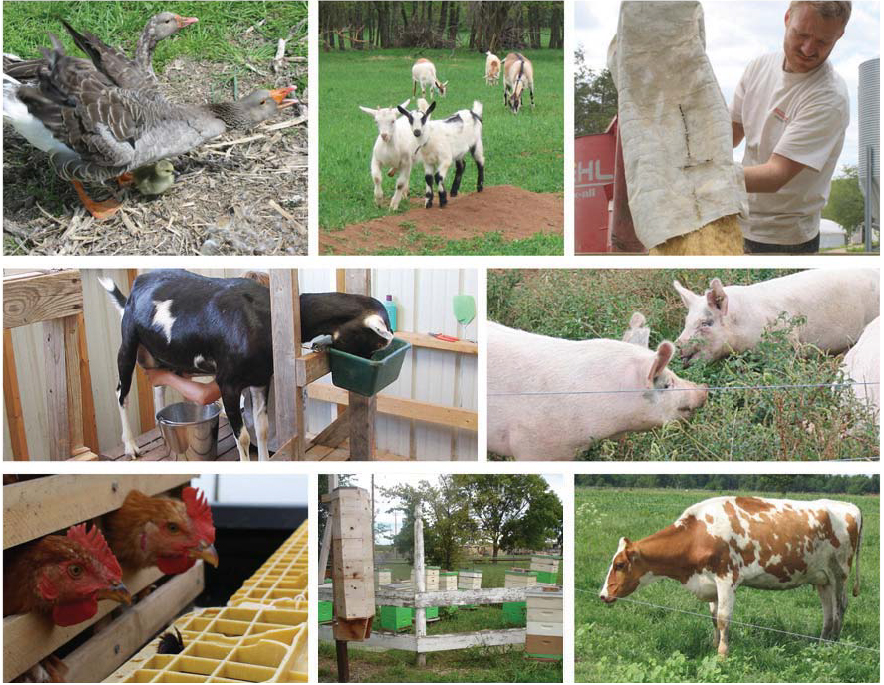

Livestock offer many benefits to a small-scale farming operation. Photo credits: Goose – Margo Hale, NCAT; Goats – Linda Coffey, NCAT; Feed – Carla Spencer, Across the Creek Farm; Goat – Linda Coffey, NCAT; Pigs – Linda Coffey, NCAT; Chickens – Carla Spencer, Across the Creek Farm; Apiary (with experimental tower hive) – Andy Pressman, NCAT; Cow – Linda Coffey, NCAT

Contents

Introduction/Overview

Concerns with Raising Livestock on Limited Acreage

Species Considerations

Bees

Poultry

Rabbits

Hogs

Sheep and Goats

Cattle

Summary

References

Resources

Abstract

Livestock are a potentially profitable enterprise for small-scale agricultural operations. Livestock can offer a farm new revenue streams, as well as increased fertility and weed control. Benefits and challenges of raising livestock on a small farm are discussed here, including particular considerations related to producing poultry, rabbits, hogs, sheep and goats, bees, and cattle. Resources for further reading are provided.

Introduction/Overview

With growing interest nationwide in sustainable agriculture and local foods, there are many opportunities for those interested in small-scale agricultural operations. Many beginning farmers or farmers in more urban areas do not have access to large parcels of land. Fortunately, there are many agricultural enterprises that lend themselves to small-scale intensive production.

Many small-scale farming operations have a vegetable crop focus. With a limited land base, high-value specialty crop production is a logical choice. However, don’t overlook livestock as a possible enterprise for small acreages. There are many benefits to raising livestock on a small scale.

Livestock make a great addition to a specialty crop operation. In addition to helping diversify enterprises and income streams, livestock can provide many other benefits. For example, their manure can be used to fertilize crops. They can provide weed control in (geese) and around (sheep, goats) gardens. Waste produce can be fed to livestock, and the animals can graze and fertilize gardens at the end of the season. This provides nutritious feed to livestock and helps eliminate garden waste.

In addition to providing benefits for the farm, adding livestock to your operation can also benefit your community. There is a growing demand for locally grown food, but in many places finding locally produced livestock products is difficult. By raising livestock and marketing their many products, you can help diversify the local food offerings in your area.

Another benefit, especially if you are direct-marketing your farm products, is that livestock may attract customers to your farm. Customers enjoy seeing livestock on a farm. If your animals can be seen from a road, it may cause potential customers to stop and learn more about your operation. Additionally, the small size of sheep, goats, rabbits, and poultry make them relatively child-friendly.

Concerns with raising livestock on limited acreage

While there are many potential benefits from adding livestock to a small-scale farming operation, there are also many challenges.

First of all, you will need to investigate the zoning laws where you live. Are you allowed to raise livestock? If so, are there any limitations about type or number? For example, in an urban or suburban location, you may be allowed to keep as many as 20 hens, but no roosters. Find out about any restrictions up front. It may be possible to petition to have the zoning changed, but this will require at least the support of your neighbors and the zoning board. It’s best to learn about any restrictions before you begin an enterprise.

If you are new to livestock production it is important to learn as much as you can before beginning your enterprise. Learning from other livestock producers is a great way to educate yourself about a particular enterprise. Unfortunately, in areas where farming is no longer common, it can be difficult to find mentors and advisors. Although reading can be a helpful way to learn about many aspects of raising livestock, not everything can or will be covered in an article or book. Finding an experienced person who can answer questions or come and look at your setup and give guidance is worthwhile. A supportive veterinarian or local Cooperative Extension or NRCS agent can be a great help. An experienced local producer who is willing to spend time with you is a huge asset as well. Beginning farmers can often “pay back” these mentors by bartering their own time (labor) or other products, and by serving as a mentor to someone else in the future. See the Resources section at the end of this publication for a list of books, periodicals, and organizations that offer education to assist you in your pursuit.

Besides learning, installing housing and fencing is another task that needs to occur before bringing livestock to your farm. It is certainly true that “good fences make good neighbors,” and learning about the appropriate fencing for your chosen livestock species, and installing that fence, is an important step before purchase. Fencing is important not only as a means of containing your animals, but as a way to protect them from predators, including neighborhood pets. For some animals, such as sheep or goats, fencing will be the largest single investment a producer makes. Visiting other farms and consulting with other farmers can help save time and effort and money. Remember that for a long-term investment, it’s best to buy quality. It is also wise to begin with a temporary setup (be sure it adequately controls the animals) until you can see how it works. Invest in permanent fencing when you have some confidence in the design and location of fences and gates.

Fencing is probably the largest investment initially, with feed usually the largest-ticket item in the long run. Feeding an animal correctly (the right amounts of nutritious feed) and economically is often a challenge, but proper nutrition is essential for health and productivity. For some species, such as chickens, providing adequate feed can be pretty simple: buy a feed labeled for the animal and follow the directions on the label. By contrast, for grazing animals you will need to learn to manage forages and then provide supplemental feed as needed. Finding an advisor and learning to monitor body condition (level of fatness; how much the bones are covered over the back and ribs) are important means of making sure your animals are receiving adequate nutrition. Feed costs may be influenced by the scale of your business (you won’t be purchasing feed by the ton, so you lose some efficiencies of scale) and by the location. A suburban area may have higher costs for feed than a more rural area. Check into costs where you are, and be sure to account for feed costs in your budget. In some areas, feed costs may prohibit raising some species of livestock.

For all livestock enterprises, feed and other costs will be incurred for weeks or months before any income is received. Cash flow the first few years (or in an expansion year) can be a real problem. Also, either drought or a harsh winter can increase the need for purchased feed. Be sure to have a plan for paying for all expenses, and think “worst case scenario.” What if you have to feed hay in July and August? What if an animal dies and you can only sell four hogs instead of five?

Most sustainable livestock operations will utilize forages as much as possible. Sheep, goats, and cattle are ruminants and should have a forage-based diet. Chickens, hogs, and rabbits can also utilize forage as a portion of their diets. The more you can utilize forages, the less feed you have to purchase. With a limited land base (five acres or less), access to adequate forage can be a challenge. It is important to understand how much pasture/forage you have available and what the realistic stocking rate is for your area and for the species you are raising. Often when livestock are being raised on limited acreage, they are more confined and fed purchased feeds (hay, grain). Purchasing feed directly affects the profitability of your enterprise.

Purchased feed must be properly stored in a secure location and protected from rain and from animal contamination (i.e., rodents or cats). This preserves the nutritive quality of the feed and also protects animal health. If a ruminant breaks into the feed supply and overeats grain, it will get sick and may die. Cats may carry toxoplasmosis and spread the disease to your livestock, or to the manager. Feed storage can be in a covered trash can in your garage, or you might need a separate shed for storing feed.

Grazing animals on a small acreage will sometimes need to be fed hay. In a dry climate, hay could be purchased and stored in stacks where livestock can’t get to it. In areas where there is rain, hay will lose a lot of nutritive quality unless it is stored under a roof. A tarp cover can protect hay from rain, but condensation will gather under the tarp, causing mold growth. In some instances, a hay grower may deliver hay in large bales or in small truckloads several times over the course of the season. Expect to pay extra for this service. If you have to haul your own hay, you will need a truck. Remember to allow time in your budget for acquiring, hauling, stacking, and feeding the hay. Ask your mentor how he handles feed acquisition, storing, and feeding to livestock.

Another concern of livestock production is manure handling. If you are raising animals on pasture, then you shouldn’t have much of a manure issue, as they will be depositing their manure directly onto the pasture. If animals are being raised in confinement, or if they gather in a barn, then you will have to deal with manure. For sanitary and health reasons, it is important to keep barns and holding areas free of excess manure. Manure can be composted or applied directly to pastures and crops. Managing manure is not only important for the health of your animals, but also for neighbor relations.

When choosing a livestock enterprise, take into consideration your local climatic conditions. If you live in an area with harsh winters, adequate shelters will be necessary. Harsh winters pose challenges in providing water to livestock and in young animal survival. Because of these concerns, it may be advantageous to raise animals that do not overwinter. For example, meatbirds are raised and harvested before winter. Feeder pigs also can be purchased in the spring and sold before winter. If sheep or goats are part of the farm, breeding can be planned so that lambs or kids are not born until springtime. Heaters for water tanks may be a good idea as well. Colder climates with shorter growing seasons also affect the amount of forage produced and how many months your animals can graze in a year. The shorter the growing season, the more feed you will have to purchase.

Hot weather also brings difficulty. Pastures stop growing, animals eat less, and can overheat and die. Internal parasite infections may rise to dangerous levels when animals are stressed by heat. Providing shade and cool, fresh water, and being watchful for disease problems and for weight loss are all good precautions. If heat is accompanied by drought, as is often the case, managers will need to prevent overgrazing and provide supplemental feed if the pastures get too short. Reducing the number of grazing animals on the farm, or leasing extra land, may also help the situation.

During all seasons, farmers must do what they can to protect the natural resources of the farm: the forages, soil, and water. Managing grazing, preventing access to pastures during severe droughts or very wet periods, keeping plant cover on land to prevent erosion, and managing manure and grazing to prevent water contamination are primary responsibilities of the land manager. See the Resources section for more information on protecting land and water.

Before you bring animals to your farm, try to locate (through asking neighbors, searching the phone book or Internet, or checking with your mentor) a veterinarian who will help if you have trouble. If you start with healthy animals and keep them adequately nourished and in a low-stress environment, you will usually have “good luck” with animals. Still, not all animals will stay healthy. What will you do if an animal gets sick, or injured? While many areas have veterinarians nearby, not all veterinarians work with livestock. In addition to finding a veterinarian, you should acquire some books to learn the basic preventative health care measures for the species you are raising, and to learn something of the main diseases that may be a problem. Ask your local Cooperative Extension agent and your mentor about what diseases to watch for.

If you see an animal that is “not acting right,” it is important to act quickly to figure out the problem. In the first year or two, you will probably want to call your mentor and have him or her see the animal. If they agree that there is a problem and you need a veterinarian, call; this is not only good for the animal but for furthering your education. Veterinary expenses may be higher some years as you run into problems, but if you learn from each experience, expenses should drop over time. Always ask how you might have prevented the problem: Is there a vaccine? Do you need to improve nutrition? Is sanitation adequate? Getting help promptly increases the chances of saving the animal and of preventing others from getting sick.

Another important concern is keeping yourself and your family safe. It is especially important that you understand the risks of zoonotic illnesses and of injuries that might happen when animals are stressed. Learning about animal behavior and reactions, and proper handling, will help a great deal in making your livestock enterprises a good experience. Your mentor will be vital in showing you how to perform management tasks and how to safely work around the animals. Handling animals calmly and quietly helps. Always be cautious around these classes: males, females with young, animals that have not been handled (and so are afraid of people), animals that have been handled too much (and so are not afraid of people). For example, a lamb that was cute and friendly when fed from a bottle will grow up to be a dangerous ram, because it has no fear or respect of people. Similarly, a sow that was perfectly friendly and easy to deal with will be a different creature the day after she gives birth.

Even animals that are not aggressive can cause injury. A frightened sheep that is cornered could jump and knock down a child. There are ways to lessen risks; awareness is the crucial first step. Besides consulting your mentor, take time to read about the species you raise, and learn safe handling. Click here for more information about animal behavior.

Besides locating a mentor, an advisor knowledgeable about soil and water conservation, and a veterinarian, a farmer will need to identify a couple of sources of labor. It is best if your family can help, and the responsibility of looking after animals is character-building for children. But when you need to be off the farm for more than a day, you need someone to care for the animals. Willing neighbors, your mentor, responsible children from your local 4-H club or FFA chapter, and older farm-raised adults who have time on their hands are all good options. Plan to write complete instructions and to give your chore person a tour, giving verbal instructions. Leave them your cell phone number. And pay them well, in either dollars or some other compensation, as a competent and responsible person to fill in allows the farmers to have some freedom.

One of the side benefits of entering livestock production is that it will encourage you to get to know neighbors and build a network of connections to work cooperatively. Besides the helpers already mentioned, a small farm may need someone to haul livestock to a processor or market. They will need to locate a feed source, and a fencing supply company, and someone with a tractor to help occasionally with clipping pastures or spreading manure. Talking with other producers is the best way to find those local people you will need to be successful. Joining an association of producers is a good use of time and energy. Check with your local Cooperative Extension office to learn of available groups, or to get help in forming a new group.

In addition to finding support in your neighborhood, you will need to have good relations with your neighbors. You can help this along by communicating your plans, installing good fences to prevent your animals from making unwelcome visits, and taking good care of your farm so that it looks (and smells) healthy and attractive. This will mean composting manure, keeping the farm “picked up” (no old parts or tangled rolls of wire lying around), promptly dealing with mortalities by composting well, and keeping animals well-cared-for. If your neighbors are very close to your farm, they may be bothered by roosters or your guardian dogs. Be sure to control your animals, and remember that an occasional gift of farm products or the offer to let the neighbors bring children over to pet the animals can help a great deal.

If you are raising livestock for meat, a prime consideration that must be investigated early in your planning process is the availability of processors to turn your animals into meat. Marketing options are contingent on the type of processing you can access. In many areas, this is the single-largest stumbling block to raising and marketing livestock on a small scale. There are three levels of meat inspection: federal, state, and uninspected or custom-slaughter plants. State-inspected meat cannot be sold outside of that state, and uninspected meat must be for the owner’s use only and labeled “not for sale.” Federally inspected processing plants that are willing to take a small number of animals, or even keep your meat separate, are very hard to find. You might have to base your marketing on using state-inspected facilities, or make arrangements with custom processors. A good option (if your customer wants an entire animal) is to sell the animal live, transport it to the butcher for your client, and have the client pick it up and pay processing fees. Check with your state department of agriculture for your state’s regulations on processing, selling, and on-farm slaughter. Call the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service hotline at 1-800-535-4555 with any questions about federal regulations. The Niche Meat Processor Assistance Network also offers information and resources about meat processing regulations, and contacts for locating a processor.

| Table 1: Processing Options | |

| There are several different levels of processing, and access to them will affect how you can market your animals. | |

| Federal- or USDA-inspected Plants | Federal plants can process meat for nationwide sale. |

| State-inspected Plants | Only about half of the states have a state inspection program. State-inspected plants can process any meat, but it is stamped for sale only within that state (unless the processor participates in the new USDA program that allows for interstate sale of specially inspected meat.) |

| Custom Exempt Plants | A custom plant processes for individual use. The meat must be stamped “not for sale.” |

| On-farm Slaughter (exempt from inspection) | Animals are processed by the owner for individual use (regulations vary by state). |

If you are planning a meat business, you must factor in the cost of processing, and of hauling the animals to the processor and picking up the meat afterwards. It is possible that the processor’s share of the income will be more than yours. Remember that selling meat (or eating it) is not possible without someone performing this step, and a good processor is well worth the price.

Having determined your marketing options, you are now ready to think about the scale of the enterprise. Will you be raising livestock for home use only, or for home use and for commercial production? Your family should agree on goals for the farm. Your goals and plans must factor in the reality of your farm. How much labor and how much land do you have? Do you have a working knowledge of livestock, or is that one of the things you will acquire through your enterprises? It is wise to start with a small number of fairly inexpensive animals (“trainers”)—making sure they are healthy—and learn basic production and handling and marketing by raising just a few at first. This is a risk management technique: you will make mistakes but they won’t be as devastating. You will also learn whether you like the animals well enough to continue; if so, you can expand.

How much you can expand depends on your available land base. You must protect the forages, soil, and water of your farm. If you don’t overstock the farm, livestock can improve the forages and soil, and therefore increase water retention on your farm. However, overstocking can deplete all the resources and contaminate the water. You must think of long-term consequences, not short-term gain.

How much income can you expect from your livestock? That depends on your choice of species, and the way you manage and market them. Some rough indication will be touched on in the individual species sections of this publication. It is a good assumption that no livestock enterprise will allow you to get rich quick; use a sharp pencil and realistic numbers to figure out possible income and expenses. Budgets are provided, but you must always do homework to get figures for your own area. There are many things that can affect your profitability and income, including production efficiencies, feed costs, types of products, marketing streams, and what pricing your local area can support. These factors are different for all operations, which is why it is so important to keep records and determine the best products and pricing for your location.

That sharp pencil should be used all through your farming experience. Tracking expenses and income, observing yields, noting what market prices were for a certain date and a certain weight of animal, learning what your actual costs of production are, and noting labor use will all help in planning for next year and in adapting enterprises for better results. Keeping and reviewing good records are what will allow a small farm to be more than a hobby—and allow a farmer to determine whether it is a viable business, or an enjoyable hobby, or a money pit. Each of those situations is possible with any livestock enterprise. Record-keeping forms can be found in many production books (see Resources) or can be designed to fit your needs. These records are vital at tax time or whenever you are making decisions.

Once you have developed expertise with your animal enterprises, and built your network of helpful people (mentors, processors, veterinarians, chore helpers, vendors), and determined that you can make a profit with the farm, you may be ready to expand operations. Sometimes a neighbor will be willing to let you use their land if they believe your grazers will improve it, or someone nearby might lease you acreage. Adding land adds fencing cost and time, and perhaps travel time, and also presents the challenges of providing water and adequate observation.

Another possibility for increasing income might be to stack enterprises. For example, perhaps you could add sheep to your laying hen operation, and let them graze ahead of the hens to keep grass manageable. A few pigs might be helpful to use extra milk and whey from your dairy goat operation. Or, you might diversify your product mix by selling breeding stock as well as meat animals.

Another potential way to add revenue to your farm is to add value to raw products. For example, make soap using some of the milk from your goats, process wool into yarn, or make hogs into sausage. Diversifying your product mix can also help you reach more customers and greatly increase your network and profits. Remember that each new product takes time, expertise, and possibly additional equipment, as well as marketing. Track time and expenses so you will know which diversification strategy was helpful, and which was more trouble than it was worth.

See the Resources section for books, websites, and publications to further your understanding of managing a small farm that includes livestock. Some key considerations relevant to particular species follow.

Species Considerations

Bees

Small-scale intensive farmers are using small acreages to grow an abundance of food that is safe and sustainably raised. Many of them are beginning farmers with limited resources who are producing crops and livestock on small land bases. Others are currently farming on a larger scale and are starting to see the benefits of diversifying or downsizing their operations. Much of the success of all of these farmers is related to the pollination services of the honey bee (Apis melifera). This section provides a general overview of keeping honey bees on a small-scale farm and includes legal and safety information on keeping bees in populated areas. Urban environments can provide excellent foraging for bees, with less exposure to pests, diseases, and even pesticides, which can be devastating to a colony.

The Value of Honey Bees

Over 150 crops grown in the U.S. are pollinated by honey bees, including many fruits, berries, nuts, melons, cucumbers, broccoli, clovers, and alfalfa. These crops make up one-third of the U.S. diet and contribute over 14 billion dollars to the U.S. agricultural economy (ABF, 2011). While crops such as blueberries and cherries are 90% dependent on honey bee pollination, almonds are 100% dependent on honey bees for pollination. Of the honey bee colonies in the U.S., two-thirds travel around the country each year pollinating crops during bloom time, including over one million colonies in California alone, just to pollinate the state’s almond crop. According to the USDA’s National Agriculture Statistics Service (NASS), there were more than 2.7 million colonies in the U.S. in 2010 (USDA-NASS, 2011). The honey bee is one of the most beneficial insects, yet colony numbers in the U.S. have declined 45% over the past 60 years (NAS, 2007).

In addition to the tremendous value honey bees provide as pollinators, they also provide agricultural products, such as honey, pollen, and propolis. Close to 200 million pounds of honey were harvested in 2010, with a retail cost of around $1.75 per pound (USDA-NASS, 2011). While there isn’t much money to be made selling honey on a small scale, there are several value-added products that can be made from the produce of the hive, such as candles and mead, a wine made with honey.

Starting an Apiary

The Legalities of Beekeeping

Prior to establishing an apiary, it is important to understand the legalities involved with keeping honey bees in your area. Many states require the yearly registration of hives through the department of agriculture. This may involve a yearly fee for a permit as well as an inspection for disease. For more information on registering bees, contact your state department of agriculture or visit the Eastern Apicultural Society’s State Associations page for a listing of state services.

An inspection may also be required for transporting bees. Keep in mind when moving bees that if a hive is moved more than five feet from its original location, the hive must be moved at least three miles away so that field bees do not return to the old site and become lost (Sammataro and Avitabile, 1998).

A local municipality may also have its own set of rules and regulations for keeping bees. As more people become interested in keeping honey bees, many cities across the country have changed local ordinances to allow for keeping bees on a small scale. Whether the hives are located on a small-scale farm, in a backyard, or on a rooftop, local ordinances are created for the safety of the community, the beekeeper, and the bees. They specify the number of hives allowed, the types of hives that can be used, and where hives can be located. Bees that are kept in populated areas need to be managed appropriately so that they do not become a nuisance.

“Keeping bees successfully in a populated area requires an intimate understanding of basic bee biology, property rights, and human psychology” (Caron, 2000).

Beekeeping Support

Setting up a hive and maintaining bees can be an exciting and easy way to increase crop yields and expand production on your small-scale farm. As with any type of livestock, a number of issues can occur with keeping bees. These can range from protecting the hive from pests and disease to preventing swarms. In addition to familiarizing yourself with any local beekeeping regulations that may exist in your area, it is also important to have a good understanding of how to keep bees prior to bringing any bees onto the farm. There are many great resources available for education on bees and beekeeping. Manuals are good to have on hand, but there are also many educational courses offered. State and local beekeeper associations provide educational outreach and materials, and offer updates on regional beekeeping concerns. In addition, they provide networking and mentoring opportunities where beginning beekeepers are matched up with an experienced beekeeper in their area.

Related ATTRA Resources About Bees

Alternative Pollinators: Native Bees

Beekeeping: Considerations for the Ecological Beekeeper

Beekeeping/Apiculture

Hive Location

Although local ordinances may dictate the location of a hive, particularly in urban areas, there are several factors to consider for locating hives. Honey bees can forage on pollen and nectar that are four miles away. It is important to consider how the bees may be a disturbance to neighbors. Consulting with immediate neighbors will help assure that the bees do not pose a risk or harm neighborly relations. This is also an opportunity to reduce fears and misconceptions about honey bees and to educate people on the crucial role honey bees play in food production. Neighbors will appreciate a jar of freshly harvested honey, so be sure to share your harvest, especially since the pollen and nectar may have come from their property.

Orientation

Bees are content and less aggressive in the sun. Orienting the hive entrance to the east or south will increase the amount of direct sunlight for the day, especially during the winter months. Afternoon shade during the summer months will help to cool the hives, and this can be achieved by having a windbreak to the north. A northern windbreak will also provide protection to the hives from chilling winds and drifting snow during the winter months. Ventilation is a key component to hive orientation, and hives should also be kept dry. Placing the hives a few inches off of the ground will help with air circulation, and tilting the hives forward will help with water drainage. Using an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Bottom Board, designed to monitor and reduce Varroa mite populations, is also a good way to increase ventilation and drainage.

When leaving a hive to gather food or water, bees will fly 3 to 6 feet above the ground. Having a hedgerow or fence that is at least 6 feet high will force the bees to fly above head level. A barrier can also be a “good neighbor policy” by keeping the hives out of sight. In addition, the use of a sturdy fence will help prevent curious children from exploring near the hives.

Water

Bees use fresh water to cool the hives and to dilute the honey that is fed to the young. During the warmer parts of the year, a strong colony of bees can consume over a quart of water per day. They tend to collect water from the nearest source, and once bees use a particular water source, they tend to continue using the same source (Caron, 2000). It is difficult to prevent them from returning to an undesirable source such as your neighbor’s swimming pool, pond, or bird bath. Providing a constant supply of fresh water close to the hives, starting in the spring when the bees start flying, can help prevent the bees from becoming a nuisance to your neighbors and reduce the chances of someone getting stung.

Rooftops

Many rural beekeepers keep hives on top of roofs to protect the hives from bears, and city rooftops also offer suitable locations for an apiary. The City of Chicago has maintained hives for over a decade on the roofs of City Hall and other municipal buildings. While having an apiary on a rooftop may prevent the bees from becoming a nuisance to the neighbors, there are several other factors to consider.

First, the distance off of the ground and access to the roof are important aspects to a rooftop apiary. Keeping bees off of the ground requires equipment to be taken up and down. This can include supers that are full of honey and can weigh up to 40 pounds. In addition, the equipment that is taken to and from the hives may contain bees. Practice moving equipment to and from a rooftop prior to installing bees to get a general sense of what it will be like to manage a rooftop hive. Although there is little information available on the maximum height off the ground for hives, remember that the higher the hive, the harder bees will have to work on their return flights.

Second, the temperature of the roof and wind conditions are important considerations for rooftop hives. While the ambient temperature may not be a direct factor, the heat off of a roof will cause the bees to need more water. Providing a water source on a roof may be an inconvenience to the beekeeper, but otherwise the bees will have to collect and carry water up to the hives. Roofs can also be windy, and a windbreak may be necessary to protect the bees.

Hive Management

There are several management techniques that will help keep bees calm and non-aggressive. Bees tend to become aggressive—genetics aside—when there is a lack of pollen, nectar, and good weather to forage, or when there is a disruption to the hive. Potential and common disruptions include inspecting the hives, animal odors, and vibrations, such as those from nearby lawn mowers. Aggressive bees should not be kept in populated areas. Their behavior can often be dealt with by requeening the hive with a new queen.

Working the Hive

Once a hive is opened for an inspection or otherwise disturbed, the bees can become temperamental. A typical bee hive contains thousands of worker bees that are all capable of stinging. Once a bee stings, a pheromone is released to warn the other bees in the hive and trigger them to attack. Gently smoking the hive encourages the bees to engorge honey, which calms the bees and reduces the likelihood they will sting.

A hive’s disposition is also influenced by the time of day and weather when the hive is worked. Bees tend to be more docile on warm sunny days and are more likely to attack when the temperature is below 65 degrees Fahrenheit or when it is cloudy or raining (Caron, 2000). Working a hive in the middle of the day is also preferred over the early morning or late afternoon. During this time most flowers produce their nectar, and so the bees are active and out foraging. Rain dilutes nectar and bees often wait to forage until the sun has evaporated the moisture, making the nectar more concentrated. One time not to work bees mid-day is when there is a dearth, which usually takes place between honey flows in the summer. This causes bees to rob other hives and makes bees defensive of their own hive. Spending a limited amount of time examining the hive and covering honey supers when robbing is prevalent will reduce the amount of robbing when there is little food available.

Swarms

Swarming is a hive’s natural tendency to establish a new bee colony. Swarming usually takes place in late spring when many of the worker bees (females), drones (males), and one or more queens leave the original colony to form a new one. During a swarm the bees are filled with honey and are usually gentle and not inclined to sting. Strong colonies with good laying queens are most likely to swarm. Preventing swarms (and knowing how to catch a swarm) will not only make sure that there are no colonies being established outside of the hive, but will also keep the hive strong and better able to survive through the winter. Swarm prevention can include the following:

- Providing sufficient room in the brood chambers and honey storage areas

- Reversing brood hive bodies

- Dividing the colony if there are queen cells

- Requeening the hive with a young queen

- Setting up a “bait hive” in hopes that the swarm will discover it

Factors Affecting Hive Health

With the rise of industrial agriculture and other stresses, bees have been struck with a multitude of pests and diseases that have caused extensive damage to the honey bee population. Pests include the parasitic Varroa mite, the tracheal mite, and the small hive beetle. Varroa mites feed on honey, brood, and adult bees, and have become resistant to chemical miticides over several generations. Organic controls are effective and require a good understanding of Varroa mite’s life cycle and thorough monitoring, especially during a honey flow. Diseases have infected both the brood and adult bees, and include American and European foulbrood, Nosema, and Israeli Acute Paralysis (IAPV).

While most colony deaths since the early 1980s have been attributed to the parasitic Varroa mite, beekeepers have recently been experiencing losses associated with a crisis called Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). CCD was discovered in 2006, when beekeepers observed few to no adult bees in hives with a queen, brood, and honey present. Honey bees leave the hive in search of pollen and nectar and do not return to the colony. Some beekeepers reported losses of 30 to 90% in 2006 and 34% in 2010 (CCD Steering Committee, 2010).

There has been no single agent discovered that is responsible for CCD, although there are major research studies being implemented, with the participation of the USDA Agriculture and Bee Research Centers, universities such as Penn State University, University of Nebraska, and the University of Minnesota, and countless numbers of beekeepers. Studies are indicating that pesticides, parasites, and pathogens are associated with CCD. In part, the use of genetically engineered crops with herbicide resistance has eliminated pollinator habitats from crop fields and field borders (Ellis, 2011). Secondly, the large deployment of neonicotinoid and phenylpyrazole pesticides known to kill bees has led to detectable levels of those pesticides in the pollen and nectar of plants. Beekeepers such as Gunther Hauk of Spikenard Farm Honeybee Sanctuary in Virginia and Ross Conrad of Dancing Bee Gardens in Vermont are sharing the wisdom of organic and biodynamic beekeeping methods that do not undermine the bee’s immune system, as a means of preventing CCD.

A Word about Grazing Livestock

Managed grazing can be beneficial to honey bees and other pollinating and beneficial insects. In order for managed grazing to be effective, the combination of timing, intensity and duration of each rotation, and the type and breed of livestock best suited for the site need to be in balance (Hoffman Black, Hodges, Vaughn, and Shepherd, 2007). Grazing periods should be short and planned around allowing flowers to bloom to provide nectar and pollen sources. Over-grazing livestock can be detrimental to bee habitat as livestock can damage soil structure and plant communities. For more information on rotational grazing, visit ATTRA, the NCAT Sustainable Agriculture Project.

Certification Standards for Beekeeping and Hive Products

As bees become susceptible to more pests and diseases, many beekeepers are practicing natural management techniques that eliminate the use of synthetic chemicals in the hive to help bees stay healthy. By following rules and regulations to meet specific certification standards, such as Organic and Demeter, beekeepers have the opportunity to certify their honey and hive products. Certified products, legally permitted to be labeled as such, can bring higher prices.

Organic Certification

Organic certification requires that beekeeping operations be in compliance with the rules and regulations set forth by the USDA National Organic Program. Bees are considered livestock and so the Livestock Standards, sections 205.236 through 205.239, and the related sections of the National List have been used as a baseline for certifying honey and other products from the hive. As with poultry, the standards require that bees must be managed organically from the second day of life, fed organically produced feed; and that the beekeeper use no prohibited substances.

In the fall of 2010, the Livestock Committee of the National Organic Standards Board recommended that specific apiculture standards be added to the organic regulations. The recommendations ensure the continued success of the growing U.S. organic honey market and include the following practice standards (NOSB, 2010):

- A forage zone with a 1.8-mile radius from the edge of the apiary and a surveillance zone of a 2.2-mile radius beyond the forage zone where there is the risk of contamination.

- Organic bee products must be from colonies and hives that have been under continuous organic management for no less than one year prior to the removal of the bee products from the hive.

- Hives must be constructed from non-synthetic materials, such as wood and metal, and not treated with prohibited substances.

- Foundation may be sourced from organic foundation, plastic foundation dipped in organic or conventional wax, or organic or conventional wax.

Demeter

Demeter International is the world’s only certifier of Biodynamic® farms and products. The 102 certified Biodynamic farms in the U.S. follow the principles of biodynamic agriculture that were presented by Rudolph Steiner in 1924 (Demeter International, 2011). Biodynamic agriculture envisions the whole farm as a “self-contained and self-sustaining organism” (Demeter Association, Inc., 2006). Please refer to ATTRA’s Biodynamic Farming & Compost Preparation for a general overview of biodynamic farming. The Demeter Standards for Beekeeping and Hive Products describe the management practices for the natural construction of comb, winter feed containing a minimum of five percent honey by weight, and methods for increasing honey production.

Top Bar Hives

Top Bar hives have been used for centuries, and their practicality and more natural approach to beekeeping is still favored by small-scale farmers around the world. Top Bar hives allow the bees to build their own comb, and are an alternative to the standard Langstroth hives with movable frames. Top bar hives are gaining in popularity among beekeepers in the U.S., in part because they are easy to construct, relatively cheap to produce, and do not require any frames or supers. Top Bar hives tend to produce less honey, but that honey does not have to be extracted. Instead, honey is harvested as whole-comb and is either pressed or drained.

There are two types of designs for Top Bar hives; the Kenyan and the Tanzanian. The designs are similar in that they both include a sturdy box with an entrance on one side, 20 to 30 top bars, and a roof. The difference is in the sides: the Kenyan style has walls that slope inward towards the bottom while the Tanzanian has straight sides. Both designs work well; however, bees tend not to attach comb to floors, and with the sloped sides of the Kenyan-style hive, bees think the walls are part of the floor and attach far less comb, making it easier to remove the comb.

Brood is built near entrances, so placing the hive entrance on one end for brood results in the bees filling comb with honey on the opposite end. Consequently, it is easy to harvest honey, and no queen excluder is needed. A queen excluder is used in Langstroth hives, placed between the brood chamber and honey supers. It allows for worker bees to move throughout the colony but keeps the queen and drones confined to the brood chamber. As a result, the honey supers contain only honey—no brood—and can easily be removed for harvesting.

The key principle with Top Bar hives is making sure that the top bars are between 1¼ and 1½ inches wide. This is the proper distance apart to allow bees to build comb. In addition, a top bar length of 19 inches makes it convenient for starting comb and brood rearing in a Langstroth hive and later transferring it to a Top Bar hive. When starting a top bar, attaching ½ inch of beeswax, masonite, or hardwood to the top bar will help the bees start building comb in the right place. Many top bars have a groove down the center so that the starter can easily be wedged into the bar. When reusing a top bar, the starter can be achieved by leaving ½ inch of comb attached to the top bar when the rest of the comb is cut away during the harvest. Since top bars are not supported by a full frame, the comb is more fragile than in a standard hive. The comb should always face down and can be turned upside down, but should never be turned sideways.

Poultry

Poultry are raised on the farm for many purposes – egg and meat production, insect and weed control, and selling stock are a few reasons. Due to the diversity of sizes, diets, foraging behaviors and hardiness among poultry species, poultry can usually be advantageously incorporated into an existing livestock or horticultural enterprise, with a synergistic effect with other farming enterprises.

Poultry have the potential to be one of the most profitable livestock species on small acreages. Poultry have several advantages over other livestock for farmers limited by land availability: the birds’ small size, a fairly quick return on investment, and low cost of start-up, to name a few. In fact, poultry are often the first livestock that beginning farmers own, and are frequently the “gateway” animal to acquiring larger stock.

On any farm, the addition of poultry can diversify the farm’s offerings to customers through meat and egg production, provide insect and weed control, improve soils through increased fertility, and become a marketing and educational tool for customers and their children. There are many types of domesticated poultry with profitability potential on small farms:

- Chickens

- Ducks

- Turkeys

- Geese

- Guineas

- Squab

- Gamebirds (Quail, chukar, pheasants, etc)

Each species has advantages and disadvantages that will be covered below.

Commercial laying breeds, like this Commercial Leghorn, do just as well on pasture as their heritage counterparts. Photo: Carla Spencer, Across the Creek Farm

Poultry Species

Chickens

The most familiar of all poultry, chickens were domesticated around 7,000-8,000 years ago and have fed billions of humans throughout the ages with their eggs and meat. On the farm, chickens produce eggs (layers) and meat (meatbirds or broilers). Some older breeds, referred to as dual purpose, produce eggs and their carcasses put on enough meat to make a decent stew hen at the end of their laying productivity. Typically, however, layers and meatbirds are raised differently, as their management needs are quite distinct.

Layers

Historically, laying hens have been a common livestock component of American farms and homesteads. In 1910, when small farms covered the nation, nearly 88% of American farms maintained at least a small flock of chickens for commercial or family production. Laying hens are still the most common poultry on small farms.

Breed selection is an extremely important step in a profitable laying operation. Robert Plamondon, a long-time pastured poultry farmer in Oregon, estimates that modern breeds of laying hens, such as Red and Black Sex-links, Industrial Leghorns, and Production Reds, are six times more productive than non-production breeds like Brahmas, Dominiques, and Orpingtons. Choosing the most productive breeds available can be like doubling or tripling your flock size in terms of production, while cutting your feed, housing, and fencing costs to half or a third of what they would be with the more unproductive breeds.

| Table 2: The Impact of Layer Breed on Net Income | |||||

| Laying Flock

Breed |

Dz Eggs

Per Hen |

Sales @ $3.50/dz | Feed Cost

Per Hen |

Return Over Feed* | Gross

Profit** |

| Non-Commercial Breed | 8 | $28 | $21.88 | $6.12 | -$2.58 |

| 1950s-Era Commercial Layer | 16 | $56 | $23.75 | $32.25 | $22.35 |

| Modern Commercial Layer | 20 | $70 | $27.50 | $42.50 | $32.00 |

| *Feed estimated at $0.25/lb

**Gross profit is figured as return over feed minus the cost of egg cartons ($0.15/dz) and the cost of raising a pullet chick to maturity ($7.50) Source: Adapted from Robert Plamondon’s Success With Baby Chicks, page 28. |

|||||

In his book Success with Baby Chicks Robert Plamondon explains quite thoroughly the differences between various breeds and hybrid layers on pasture. He convincingly shows the necessity of using modern commercial utility layers, many of which are crosses between several breeds of chickens or independent strains developed within a breed. Examples of modern commercial layers:

- Commercial Leghorns

- Sex-Links (Red & Black – Commonly called Red Star, Gold Nugget, Cherry Eggers, etc.)

- Production Reds (strains of Rhode Island Reds)

- California Whites

Older Commercial laying breeds:

- Laying strains of Barred & White Rocks

- California Greys

- Rhode Island Reds

- White & Brown Leghorns

Unlike meatbirds, which have a turnaround as short as six weeks, production-strain laying hens don’t start laying until their fifth or sixth month, each consuming approximately 25 pounds of feed before they reach the point of lay. As a hen ages, the number of eggs laid over the course of a year decreases. Therefore, after the hens’ second year of laying, most poultry farmers remove these older, less-productive birds from their flocks. The investment in raising the hens to the point of lay is recouped by processing the spent hens for soups and stock, or possibly selling them to families and homesteaders who want their own freshly laid eggs, but are less concerned with maximizing profits.

Brown eggs typically fetch a higher price than white eggs, because most customers identify brown eggs as higher quality, healthier, or more “country”. In truth, the nutritive qualities of eggs are determined by what’s inside the shell package. However, it’s beneficial to plan for the consumer’s bias.

What about Roosters?

There are several common misconceptions concerning roosters in the flock. Is a rooster needed for hens to lay eggs? Are fertile eggs more nutritious? Are all roosters aggressive?

It turns out that a group of hens will lay eggs regardless of whether a rooster is present or not, as a rooster is needed only to produce fertile eggs. And about those fertile eggs – fertile eggs are no more nutritious than non-fertile eggs. Eggs are almost always gathered by the farmer and refrigerated soon after they are laid, and fertile eggs don’t start developing unless they’re incubated by either a broody hen or in an artificial incubator.

Many farmers keep roosters in the flock for reasons besides breeding. As the flock forages, roosters will watch over their hens, and a good rooster will constantly scan for ground and aerial predators (plus the occasional plane). A rooster will call his hens when he finds food, and many farmers feel that flocks with a rooster have less fighting, as the flock’s pecking order is more stable.

Roosters do have potential drawbacks. In urban environments excessive crowing may lead to conflicts with neighbors. Certain hens will become the male bird’s favorites, and will receive a good deal of his affection; the resulting treading from the rooster climbing on the hen’s back can cause feather loss and even lacerations on the hen. Just like people, some roosters‘ personalities are pleasant and some are extremely pugnacious. Aggressive roosters should be culled immediately.

A flock of layers can help even out the cash flow of a small farm, especially during the spring, when egg production is heavy while few crops are ready to be harvested. Winter typically brings a lull to egg production, as hens molt and/or greatly slow down egg laying due to decreased sunlight levels. There are strategies for balancing out the wintertime dip in egg production by providing supplemental lighting, or having a batch of pullets reaching point of lay during the winter months.

Processing and handling eggs are critical components of any-size laying operation. These subjects will be covered in more detail later in this section.

Freedom Rangers on pasture at Across the Creek Farm in West Fork, Arkansas. Photo: Leif Kindberg, NCAT

Meatbirds

On average, Americans eat more chicken (86.5 pounds) throughout the year than any other type of meat. Almost all chickens produced for meat in the United States are raised in Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), but consumers are increasingly seeking truly free-range meatbirds raised on pasture. There’s a demand for sustainably raised chicken, and many customers are willing to pay a premium for it.

Meatbirds are a nice complement to laying hens on a small farm. While laying hens provide a small stream of nearly constant income, meatbirds can inject slugs of profit. In the time that it takes to raise a flock of laying hens to the point of lay, a farmer can possibly raise two batches of meatbirds. Meatbirds also have the advantage of not having to be overwintered, and the short turnaround time allows the small farmer to take a break between batches of chickens.

A batch of 100 meatbirds raised with electric poultry netting in a spacious day-ranging system can be brought to harvest in just a few months on around 3/4 acre, and would require even less land using a 10’ x 10’ movable pen. The birds could be worked into a crop rotation to fertilize and weed before tillage or to glean through crop residues and gobble pests post harvest.

As with laying hens, meat breed selection is extremely important. The Cornish Cross (CX), the champion of today’s poultry industry, has been bred for the better part of the past century to do one thing – put on weight efficiently. Many pastured poultry farmers use the CX because of its advantages: feed conversion rate (amount of feed it takes to make a set amount of meat) and widespread availability due to the proliferation of poultry CAFOs across the countryside. The CX is their money maker. Other producers have problems with the CX, though, citing disadvantages of poor mobility, summertime heat losses, poor foraging skills, and leg problems due to nutritional deficiencies in feed.

On the other end of the spectrum from the CX, heritage breeds are regaining popularity, and when good markets can be found, the birds’ poor feed-conversion rates can be compensated by higher prices. Typically, though, such markets are difficult to find or build.

Fortunately, there’s middle ground for the producer selecting meatbird breeds. Several types of birds with Hubbard (an international breeding company) genetics based on the French Label Rouge Free Range Program are now being raised in the United States. Depending on the family hatchery and particular strain of birds, various names exist – Red Ranger, Freedom Ranger, Redbro, Rosambro, etc.

Pastured meatbirds are typically raised in either Salatin-style portable pens (described below) or in day-ranging setups. Both systems have their pros and cons. Many producers start off with Salatin pens, with some producers moving to day-range systems because they can be less labor intensive.

Turkeys

Turkeys are a uniquely American bird, not only because they originated in America, but because Americans eat more turkey than any other country in the world. Turkeys are appealing to small-scale producers. Even a small batch of turkeys can earn a decent profit for a farmer. Except for susceptibility to a disease called Blackhead, turkeys are extremely tough once out of the brooder. In particular, turkeys at all stages are much more heat resistant than their chicken counterparts. Unlike marketing other poultry meat and eggs, selling turkeys focuses mostly around one day—Thanksgiving.

Turkeys can be divided into two groups – Broad Breasted and Heritage. Broad Breasted turkeys are the industry standard, and are by far the most common turkey on the market. Most Broad Breasted turkeys are white, but there are also bronze varieties that are sometimes mistaken for heritage breeds. The product of intensive breeding programs and characterized by rapid growth and large amounts of breast meat, the Broad Breasted white does one thing extremely well: put on meat efficiently, although this is done at the expense of being able to reproduce naturally. These turkeys are quite hardy on pasture, and are voracious grazers, eagerly consuming any vegetation and animals that they can find.

Heritage turkeys differ from Broad Breasted turkeys in several ways. For the farmer, heritage turkeys are slower growing, and proportionally more dark meat is produced on the heritage frame. Feed conversion rates for heritage poultry vary greatly depending on the breed and strain. Some heritage turkeys, once the industry standard, are good converters of feed to meat. The production disadvantages of heritage turkeys, such as lower feed conversion and a longer grow-out period compared to the Broad Breasted varieties, can be offset by their increased price. Heritage turkeys are a unique product, transporting the consumer to Thanksgivings and Christmases past, and many families are willing to pay a higher price to provide a special experience for the holidays.

Nearly a dozen heritage turkey breeds exist, and some are faced with extinction unless more people begin to grow them. The American Livestock Breeds Conservancy (ALBC) has a wealth of information on raising heritage turkeys, including a free downloadable manual. For more information see their website.

Ducks

Ducks and geese are extremely versatile and productive poultry on the small farm and homestead. These waterfowl have been important historically, producing eggs, meat, feathers, and control of crop pests for the families that raised them.

Meat and egg production are the primary reasons for raising ducks today. Ducks are relatively easy to raise because they are extremely hardy and resistant to the harshest weather and nearly all diseases. Whether raised for meat or eggs, ducks tend to make a mess with any water source they can find. While this behavior is not a problem in large ponds, ducks raised without access to open water will “make” a pond near any waterer, and the producer must plan on managing ducks for cleanliness.

Generally, chicken and duck nutrition is similar, except that medicated feeds should not be used for ducks due to potentially fatal sensitivities to some medications. Ducks are excellent foragers, using their bills to search for insects, slugs, and other small animals in mulch, grass, and other hidden places. For this reason, ducks can be used to great success in cropping systems, removing damaging pests. However, besides insect and other animal pests, ducks will consume a large amount of plant material. The producer must ensure that the crops are not more appealing to the ducks than the pests they are trying to control.

Egg Production

While less popular than chicken eggs, duck eggs are similar; some describe the taste as “more eggy.” Duck eggs are often used in baking to deliver a richer, moister baked product. Many producers offer at least some of their duck eggs in half-dozen cartons, pricing the duck eggs similar to a dozen chicken eggs. The higher price offsets the added hen cost, larger egg size, extra labor collecting and washing eggs, and their uniqueness.

Ducks’ egg-laying habits are much different from those of chickens. Whereas chickens will search out nests to lay in, ducks are much less picky, often laying eggs out in the open. Nesting boxes should be placed on the ground, and if the ducks have access to pasture, it’s a good idea to pen the ducks up at night and release them in the morning after they’ve laid most of their eggs. Penning the ducks will assist in egg collection and quality.

As with chickens, breed selection plays a large part in determining profitability in duck production. Good laying breeds are the Golden 300 Hybrid Layer, Khaki Campbells, and laying strains of Indian Runner ducks. The Golden 300 is a strain of laying duck developed by Metzer Hatchery in California. This strain produces a lot of eggs, but will not breed true, as they are crosses between multiple breeds and strains of laying ducks. Khaki Campbells and Indian Runners are stable breeds and will breed true to type.

Meat Production

Raising ducks for meat is much the same as raising chickens. The actual rearing of the ducks is relatively easy, because the ducks are so hardy. The white Peking duck is the variety of choice for meat production, efficiently converting feed and forage to meat. Unlike the Cornish Cross chicken, though, the Peking is not a hybrid and will breed true to type. The main challenge in duck production is processing, specifically plucking. Waxing, processing at specific ages, and special scalding/plucking techniques can help. For more detailed information on plucking waterfowl, please contact NCAT Sustainable Agriculture Project.“We absolutely fell in love with raising (Peking) ducks due to their incredible hardiness… then we started processing. After two hours plucking ducks, I was murmuring to myself something that rhymes with “plucking ducks”. I shan’t repeat it here. The efficient method that we have honed for processing our Cornish Cross meat chickens is completely lame when it comes to the ducks.” – Anonymous Pastured Poultry Farmer

Geese

Once a mainstay of American agriculture, geese were heavily utilized not only for their meat and fluffy down, but also for grazing and mowing young weeds and grasses in row crops and lawn production. Weeder geese were replaced by herbicides starting in the second half of the 20th Century, but there’s still a place for geese on the small farm.

Unlike other poultry, geese can derive most of their nutrition from grazing high-quality grass, if they get supplemental feed as goslings and when grass production declines. Their minimal input requirements mean that geese can potentially be raised on the farm with little expense. The functionality of geese is impressive: they provide weed control, produce Christmas meat, supply goose down, and provide security on the farm. Geese, especially Chinese geese, are extremely vigilant, and will alarm whenever a threat is perceived. Geese can be used to protect other poultry, sheep and goats, or even the home or property. However, care must be taken to make sure that young children are not the victims of overly zealous geese.

While a market definitely exists for Christmas geese, the difficulty lies in processing them, and they will almost certainly have to be processed on farm. The processing difficulties are much the same as with ducks, but exacerbated due to the larger size of the geese.

Game Birds

Game birds include a wide range of species, many of which are at best only semi-domesticated. Commonly raised species of game birds include pheasants, quail, and guineas. Less-common species include Chukar and Hungarian Partridges.

Game birds are typically raised for one of three purposes: hunting stock, meat production, or ornamental/hobbyist use. A resourceful farmer may be able to raise game birds for release on a hunting ranch or game preserve to keep up levels of stock harvested by hunters.

Game birds are considered a non-amendable species by the USDA. That means that they are not governed by many of the federal laws concerning processing, as are other poultry like chickens and turkeys. In many areas, on-farm processing will be a legitimate option, and even the regulations of the Federal On Farm Poultry Processing Exemption will not likely apply. As long as there is no transportation across state lines, and commonsense health and sanitation considerations are met during processing and handling, federal regulations should not be a problem. State and local health laws will still apply, though, and should be considered thoroughly before proceeding.

Guineas are a special type of game bird because, besides providing meat and pest control, they are often used as watchful sentries on the farm, especially against raptors. A guinea’s boisterous alarm calls can snap a livestock guardian dog and the farmer into action, while sending a flock of chickens diving for cover. Large flocks of guineas have also been known to encircle and attack single coyotes and foxes. Depending on their use and the setting on the farm, guineas can be a watchful asset or a noisy nuisance and a source of contention with the neighbors.

Because of their wild instincts, some game bird species can be quite nervous and flighty, especially compared to more-domesticated fowl such as chickens, ducks, and turkeys. This flightiness may make sportsmen happy, but makes raising the birds on pasture exceedingly difficult; traditionally game birds are raised in pens. The pens must have overhead netting and are typically kept quite dark for at least a portion of the birds’ lifespan to reduce cannibalism in the flock. Old, existing buildings on the farm, such as horse stalls or sheds, can often be converted to raise game birds.

Nutrition

Poultry have nutrient requirements that vary by species. An essential cornerstone of any profitable poultry operation is an appropriately balanced feed ration. Generally, poultry rations can be broken into three main components – calories (grains), protein (animal or a synthetic powder), and vitamins/minerals. Many small-scale producers use GMO-free or organic rations for their poultry, adjusting their meat and egg prices accordingly.

As mentioned above, the nutritional requirements of poultry vary according to the species produced and—in the case of chickens—whether the birds are being raised for meat or egg production. Chickens need a starter ration with a crude protein around 21%, while turkey poults and other game birds need around 28% protein in their feed. If given a ration deficient in protein, young birds will be unthrifty and increased mortality rates will occur. Among chickens, laying hens need less protein—but more supplemental calcium—than breeds chosen solely for meat production. Before selecting a particular breed of poultry to raise, the farmer should become familiar with the nutrient requirements of that species.

No matter what type of bird is being raised, the old poultry farmer saying “You can’t starve a flock into profit” holds true not just in terms of quantity of feed, but also in terms of quality.

For an in-depth coverage of poultry nutrition, consult the ATTRA publication Pastured Poultry Nutrition and Forages.

Vegetarian Chickens?

For reasons of cost and consumer demand, nutritional science has engineered a synthetic amino acid called methionine. This white, synthetically engineered powder enables poultry producers to keep their flocks healthy and productive on a vegetarian diet. Unlike pigs, poultry such as chickens and turkeys cannot get all their nutritional needs naturally from a plant-based diet, due to their higher methionine requirements. If synthetic methionine isn’t used, natural animal sources such as fish or meat-scrap meal are used. The National Organic Program regulations currently contain an exemption allowing the use of synthetic methionine powder in organic vegetarian poultry diets.

Pasture

Poultry did not evolve indoors, and access to the outdoors, especially on pasture, allows the birds to express their instincts and natural behaviors. Many producers are shocked to see just how much green forage the birds —especially chickens and turkeys —will eat when given the opportunity.

Poultry that graze on pasture produce healthier meat and eggs. Yolks of pastured eggs often take on an orange color, while fat deposited in the meat of pastured poultry often is yellow, evidence of the elevated vitamin and mineral content of the meat. The increased opportunity for movement and exercise on range, coupled with the difference in diet, gives pastured poultry a different texture (often described as denser or meatier) than industrial poultry. The more-flavorful taste, meaty texture, high nutrition, and better life of poultry raised on pasture enable the grower to charge a premium price.

Not all pasture is created equal. Palatability of forages on a pasture depends on the type of plant, the stage of growth, the growing season, and the plant’s environment. Certain plants such as clovers, chickweed, and crabgrass are preferred by poultry and readily consumed at nearly any stage of growth. Many grasses, grains, and broadleaves, such as fescue, Bermudagrass, ryegrass, wheat, oats, and common weeds like ragweed and chicory are eaten while young, but ignored when mature. Once grasses and broadleaves go to seed, the leaves divert the plant’s sugars and nutrition to the formation of seeds and stalks. Poultry will not eat rank forage. Plants stressed by drought or nutrient deficiencies are also less palatable and will be grazed less than healthy, nutrient-rich plants. Mowing or grazing the pasture to a short height, no more than 3 to 6 inches, is a great strategy to delay the plant’s seed production, keeping it in the more palatable vegetative state.

With the growth in popularity of pastured and truly free-range poultry, a common misconception is that poultry can forage for all their needs. Without a doubt, poultry both need and crave vitamin-rich greens, as any farmer who’s seen a flock of chickens or turkeys devour a patch of clover can attest. However, poultry are not ruminants, and naturally get their protein and energy from both animal and plant sources.

Raising poultry on pasture differs considerably from raising other livestock on pasture. Given their small size, keeping the pasture height below half a foot is preferred for poultry. Not only does this keep the pasture grasses in a vegetative state, but it also makes it easier for the poultry to move around.

Profitable broiler production on pasture means low-cost, easily portable shelter. Photo: Leif Kindberg, NCAT

Housing

Housing ultimately depends upon the species being raised and the management system the farmer chooses. Any discussion of housing would do well to consider the reasons why the CAFO is the preferred housing and management system of the poultry industry today. Production moved indoors to control predation, prevent destruction of pasture, and reduce the influence of adverse weather, as well as to reduce the labor involved in raising poultry. Meanwhile, striving for the lowest production price means the farmer who wants to be successful raising birds on pasture must design the system with predation, pasture health, efficiency, and pricing all in mind.

The first consideration in housing is brooding, as the brooder is the place where fragile chicks are raised until they grow hardier. The absence of a protective hen means that the chicks must be provided a safe artificial shelter for growth, with supplemental heat, shelter from the elements, food, water, and freedom from drafts. A brooder can be as simple as a box or kiddie pool lined with shavings and equipped with a heat lamp, or as complex as whole buildings or sheds dedicated specifically to brooding. The scale and profit potential of the operation should determine the resources expended on the brooder.

A small producer can get around having a brooder by buying mature stock or by using broody hens to hatch chicks naturally. Producers planning on naturally brooding their chicks should be aware that this is an entirely new enterprise, and the time and expenses involved should be carefully weighed and evaluated.

Generally, poultry housing is either fixed, with the birds having access outside or not, or mobile. Mobile housing, such as a Salatin pen, hoop pen, or Eggmobile, is designed to be moved frequently. Semi-mobile housing is a compromise between the two styles, designed to be moved a few times a year. Chicken coops mounted on skids are one example.

In meat production, two types of pens are commonly used:

Salatin-style pens were named for Joel Salatin, an innovative, experienced, pastured-poultry grower in Virginia. The Salatin pens are large, floorless moveable cages that the farmer moves with a small dolly at least once a day, to give the meatbirds access to fresh grass and clean ground. Designs for the pens are readily available. Advantages of the pen system are the low housing costs, safety from aerial predators and most other predators, and control over where the manure is deposited. Disadvantages to the pen system typically involve improper pen design, overheating in the summertime, and difficulties on uneven ground.

Day-ranging methods involve a moveable pen in which the birds are secured at night, with access to pasture outside the pen during the day. Often, the pens are surrounded by electric poultry netting, as an additional layer of security, as well as to give better management over where the birds graze. An advantage to day ranging is that the pens can have floors, which can give meatbirds a place to stay dry in wet weather. The bedding on the floor, filled with manure, can be harvested, composted, and used to build soil fertility in vegetable production. Advantages of day ranging can include fewer daily moves, more options for coping with extended periods of wet weather and heat, increased freedom for the birds to move and forage, and more space per bird, generally resulting in less stress.

Related ATTRA Resources About Poultry

Growing Your Range Poultry Business: An Entrepreneur’s Toolbox

Pastured Poultry Nutrition and Forages

Alternative Poultry Production Systems and Outdoor Access

Range Poultry Housing

Fencing

There are places where a farmer wants poultry to be, and places where the birds are not wanted. If left on their own, poultry will invariably choose to visit the places where they are most unwanted—helping themselves to a few bites of EVERY ripe tomato on the vine ready for market, or depositing their manure on the farmhouse porch. Life can be very frustrating on the farm if poultry are not properly contained.

Fencing serves two purposes: keeping poultry in and keeping predators out. There are two types of fencing: physical barriers meant to contain by the material strength of the fencing material, (such as field fence, chicken wire, or netting) and electric fence, which is a psychological barrier (through pain) to livestock and predators.

In terms of cost, electric fencing, whether electric perimeter fencing or portable electric poultry netting, is generally much less expensive, and easier to install than physical fencing. However, poultry are very well insulated with thick feathers over most of their bodies, which can make keeping the birds fenced in through shock problematic. A high joule rating on the electric charger is a must, because in order to keep chickens in, the electric wire must be only inches from the ground. At such a low height, the fencing wire will often come into contact with growing grass, weeds, and brush. Therefore, powerful well-grounded chargers that are capable of operating even when grass or weeds grow up around the electric fence must be used; such chargers can also keep themselves clear of vegetation by the power of their electric pulsing. Besides the charger, the second-most-important part of an electric fence is the grounding system, which is the cause of most electric-fencing problems.

Common Poultry-Production Problems

Multi-species grazing under the protective watch of a Great Pyrenees guard dog. Photo: Carla Spencer, Across the Creek Farm

Predation

At some point, every producer has a run-in with predators. Due to their small size, poultry are readily killed by predators as small as weasels, mink and raccoons, and as large as bears and mountain lions. Flying predators from the diminutive Cooper’s hawk (aka chicken hawk) to large eagles and owls also prey upon poultry. If predation is looked upon as a flaw in husbandry, the producer will adapt quickly to incorporate a holistic management solution to stop predation problems. A farmer cannot kill or trap his way out of predation: there are too many predators.

Often, multiple precautions are employed to avoid predation, ranging from livestock guardian dogs, physical and electric fencing, watchful (and loud) guineas to secure shelter. Once the predators in an area perceive a farm’s flocks as off-limits, the local predators themselves become an effective layer of defense, as their territoriality prevents new, uneducated predators from moving in and preying upon the flocks.

Seasonal Fluctuations

Seasonality has a direct influence on poultry production and profit. The challenges are best explored by season:

Spring – As nature wakes up and comes to life, so do poultry. Spring is a wet time in most parts of the nation, and most problems during this season deal with abundant moisture and animal reproduction. Potential challenges include:

- Soil compaction and destruction of sward by poultry in wet, dormant pastures

- Disease outbreaks resulting from cool weather and damp conditions

- Potential overproduction of eggs during springtime lay

- Increased predation by predators that have young that they must feed – poultry become more attractive targets

- Late-season cold snaps can chill out early batches of young poultry

- Flooding of low-lying areas

- Severe weather like hail, tornadoes or high winds can threaten poultry, especially young birds

- Broody hens take up nesting space and cause more broken eggs

Summer –Heat and humidity are the biggest threats to poultry during the hottest part of the year. Heat-related problems:

- Losses due to overheating (especially bulky meatbirds)

- Reduced growth of pasture vegetation due to heat and drought