The Causes of Soil Compaction on Grazing Lands

Print This Post

Print This Post

By Justin Morris

In an earlier blog, we discussed what compaction is and how it negatively affects plants, soils, livestock, and even economics. But how is that compaction formed in the first place and what can be done to prevent it? Fortunately, knowing how compaction forms and how extensive it is, are the keys to knowing how to eliminate it forever.

Causes of Compaction

There are generally two major causes of soil compaction on pastures: hoof impact and overgrazing. Hoof impact is the more obvious source of compaction and happens when livestock walk over the same area creating a trail or where livestock congregate such as near water, mineral tubs, or shaded areas for extended periods of time. Hoof impact can also cause compaction very quickly when livestock walk on wet soil either during or immediately following a rain or irrigation event. However, the cause of compaction that impacts the largest area is much less obvious because there is no physical downward force involved. This subtle, yet widespread cause is overgrazing. Overgrazing is the grazing of a plant before it has fully recovered from a prior disturbance such as grazing, winter dormancy, or extended periods of no precipitation and high temperatures.

Grazing studies going back to the 1950s have shown that the amount of above-ground biomass removed from a plant without sufficient recovery before the plant is re-grazed results in the roots progressively getting shorter over time. A single severe graze where 80 to 90 percent of the above-ground growth is removed doesn’t necessarily cause roots to shorten immediately. However, keeping livestock in the same area so they re-bite the tender regrowth on plants that have not fully recovered from the prior grazing negatively impacts root growth and depth.

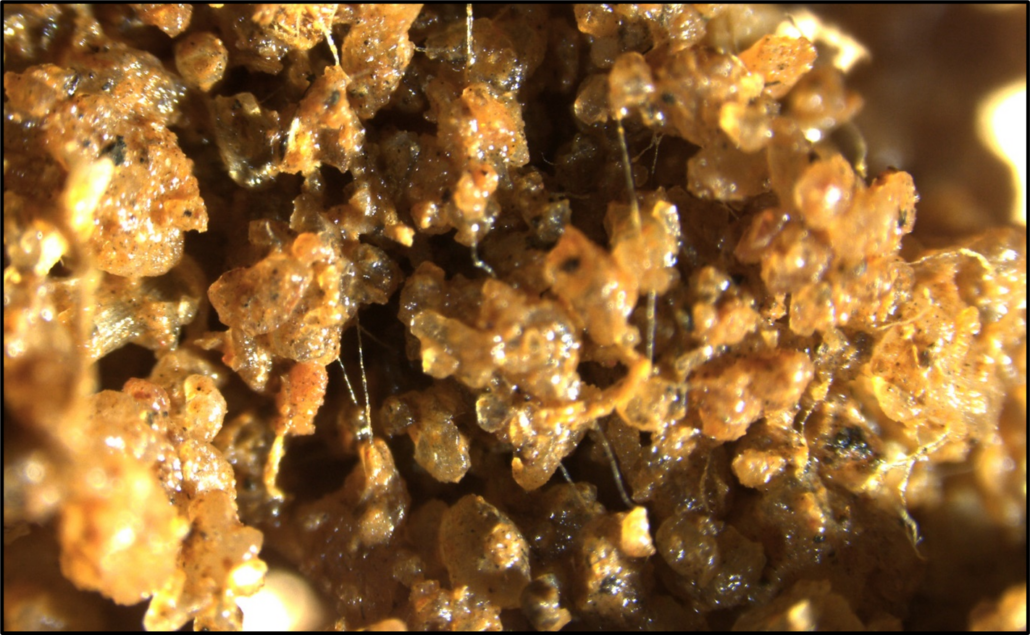

Roots are essential for healthy soil structure to be maintained. Not only do roots mechanically help to open the soil by pushing their way through the soil, but more importantly they release hundreds of carbon-based compounds like sugars and amino acids, a process known as root exudation. Root exudates are a food source for bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi. These carbon-based compounds are sticky which facilitate soil aggregation. The bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi also create glue-like compounds that allow sand, silt, and clay particles to begin clustering together to form what are called soil aggregates (see photo below).

Enhanced view of microbial soil life creating thread-like structures that aggregate soil particles forming pore space to hold water and allow gas exchange. Photo: Phillip Lee

Very dense and compacted soil clod breaking off in horizontal plates underneath a 3-inch sod layer. Photo: Justin Morris

Besides root growth and depth, the growth phase of grasses when they’re grazed and the severity of the graze affects the amount of root exudation. Research has shown that the amount of root exudates was lowest when: 1) leaves were removed in the vegetative phase (phase one); and 2) when plants were grazed severely (close to the pasture surface). If it follows that the amount of exudates can be directly correlated to the amount of soil aggregation that can take place, then grazing plants at the elongation growth phase (phase two) or later and a moderate level of grazing severity would be best for promoting the soil aggregation process. I have also found that what is best for soil aggregation is also better for plant health and livestock nutrition. Coincidence? I don’t think so.

As soil particles begin aggregating, a tremendous amount of space is created within and between aggregates that allows water to infiltrate and be held in the soil for later plant use. At the same time, sufficient space is created to allow carbon dioxide to be released into the air so it can be absorbed by plants to continue the miracle of photosynthesis. In the absence of roots feeding soil life, soil aggregates begin to break down and the soil collapses on itself creating a dense often platey structure with few roots and minimal soil life (see photo at right).

An Ounce of Prevention is Worth a Pound of Cure

Because compaction is mostly caused by overgrazing, the solution to this invisible problem is proper grazing stewardship. What do I mean by proper grazing stewardship? Grazing stewardship that focuses on building soil aggregation through:

- Livestock arriving when plants are at least in the elongation growth phase (phase two)

- Moderate levels of grazing severity (40 percent or less, depending on the site)

- Full plant recovery

In situations where minor compaction exists, proper grazing stewardship and the strategic planting of annual forage mixes are an excellent solution. However, for situations where major compaction exists, greater intervention beyond grazing and annual forage mixtures may be needed to get rid of the compaction. But before we get into that, let’s next discuss how to easily diagnose compaction using very simple, low-cost tools. Stay tuned for an upcoming blog.

Related ATTRA Resources:

This blog is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. ATTRA.NCAT.ORG.

NCAT

NCAT

NCAT

NCAT